Analysis: What happens in the early states, where the former VP is trailing, offers clues about how the nomination might turn out.

Joe Biden is the national front-runner in the Democratic presidential race. He is holding a steady lead in national polling, and his campaign boasts of the firewall he's established among African American voters, who may be the key to victory in the Feb. 28 South Carolina primary and who have backed the ultimate winner in every Democratic nominating contest since 1992.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

That's the good news for Biden.

The bad news is that in the first two voting states, he's trailing. In fact, according to an average of the polls, he's running in fourth place in both Iowa and New Hampshire.

If that holds, it will place Biden on the perilous side of history. Traditionally, the results from Iowa and New Hampshire play a dramatic role in winnowing and clarifying presidential fields. Since the dawn of the Democratic Party's modern presidential primary system in the 1970s, no candidate has lost contested races in both Iowa and New Hampshire and still gone on to win the nomination.

This poses some key questions:

- What happens if Biden whiffs in the first two states? Would it cause his support elsewhere to collapse, clearing the way for a rival to grab control of the race?

- How about if he splits Iowa, which caucuses Feb. 3, and New Hampshire, which votes Feb. 11 — would that be enough for Biden to shore up his national standing?

- Is it possible that the first two states just don't matter that much anymore, that the nationalization of politics now allows for a candidate to absorb back-to-back blows and emerge none the weaker for it?

History can't give us a definite answer, but it offers some clues. So, let's take a closer look.

First of all, the list of contested Democratic presidential races since 1976 isn't long: There are eight examples. So the historical "rule" that candidates who lose Iowa and New Hampshire don't win nominations isn't built on the deepest of foundations.

Plus, the dynamics that defined each of these campaigns vary widely. On that basis, we can probably toss out two that just aren't that relevant to Biden's situation. In 1976, Hubert Humphrey led in a Gallup national poll taken just before the Iowa caucuses. But Humphrey wasn't actually a candidate, and never ended up being one. So there's not a ton to be gleaned.

The same goes for 1988, a mess of a contest for Democrats. Technically, Gary Hart was the front-runner heading into Iowa, but he was already being written off. Felled by a sex scandal in early 1987, Hart had re-entered the race just before the New Year. He jumped to the top of the polls, but he faced hostile media coverage, had no organization, attracted few endorsements and little money. His numbers — nationally and in the early states — were dropping by the day. So, again, we don't have a meaningful Biden parallel here.

We can also toss out 1992, a year in which Iowa was ceded to favorite son Sen. Tom Harkin by his opponents and ignored by the media. Practically speaking, Iowa didn't happen in '92.

The remaining six races, however, do contain relevant elements. To understand what they might portend for Biden, we can split them into three categories:

1. National leader wins both Iowa, New Hampshire

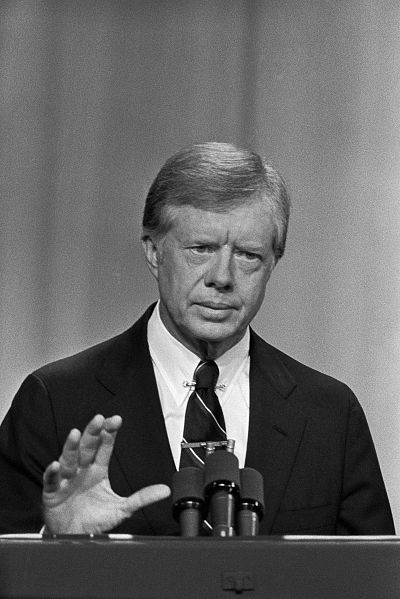

In 1980, President Jimmy Carter fended off Ted Kennedy in both states and went on to be re-nominated. Carter's strength was a late development, spurred by the onset of the Iranian hostage crisis in November 1979. Prior to that, Kennedy had led Carter in polling and seemed poised to grab the nomination from him.

In 2000, Vice President Al Gore ran with the full support of his boss, Bill Clinton, which helped clear the Democratic field — except for former Sen. Bill Bradley. When Gore won a sweeping victory in Iowa and held off a late Bradley charge in New Hampshire, the race was effectively over. Gore remains the only Democrat in the modern era to win every primary and caucus in a contested nomination race.

What it means for Biden now: Carter and (especially) Gore were stronger front-runners, and held polling leads in both Iowa and New Hampshire. But it's worth remembering that Biden, while technically in fourth place, is within 10 points of the lead in both states. If he could engineer an Iowa victory, he could easily roll through New Hampshire and beyond.

2. National leader wins one or the other, not both

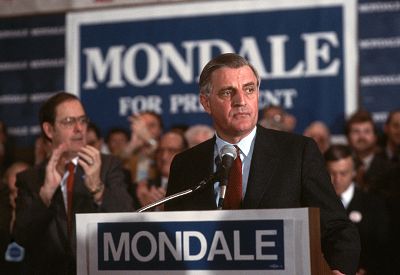

In 1984, Walter Mondale, like Biden, was a former vice president who loomed over the rest of a large Democratic field (although Mondale was typically faring about 10-15 percentage points better than Biden now in national polling). Mondale also enjoyed strong early support from black voters, who were split between him and the Rev. Jesse Jackson.

When the voting began, Mondale won Iowa easily, but his victory was expected. It was the distant second-place candidate, Gary Hart, who then received a burst of media attention and rolled to an upset win in New Hampshire.

Suddenly, Mondale's grip on the nomination was threatened. The race then moved South for the next set of contests, with Mondale's fate on the line. Jackson was making a powerful pitch to black voters, but Mondale had just enough residual support from them to eke out campaign-saving wins in Alabama and Georgia. His ship steadied, and he went on to win the nomination.

What it means for Biden now: There are two big differences. One works against Biden: Mondale, a Minnesotan, enjoyed a massive built-in advantage in Iowa, where he led wire to wire. This is significant because it meant there was never any serious chance Mondale would lose both lead-off states. Biden, obviously, does face that risk.

But if Biden can somehow pull out a win in one of the first two states, Mondale's example becomes quite encouraging for him. This is because of the other key difference: Biden, so far, has faced less competition for the black vote than Mondale did. A December 1983 Gallup poll put Mondale not far behind Jackson among black voters, 36 to 27 percent. By contrast, a Quinnipiac poll two weeks ago put Biden's black support at 43 percent, with his nearest rival — Bernie Sanders — all the way back at 11 percent.

In 2008, Hillary Clinton was also the national front-runner who lost the nomination after going one-for-two in Iowa and New Hampshire.

Her main opponent was Barack Obama and for the year leading up to the primaries, Clinton had enjoyed solid national leads. She was also competitive with Obama among African American voters, and was endorsed by a number of high-profile black leaders.

But when she lost the Iowa caucuses (technically finishing third, slightly behind John Edwards), the ground shifted dramatically. At first, Clinton looked poised to suffer another loss in New Hampshire, threatening to end her candidacy. Instead, she pulled out a surprise victory, thanks to a late surge of support among female voters.

She then won Nevada, too, but Obama's Iowa breakthrough had altered the fundamentals of the race. This became clear when South Carolina's primary results came in. Obama had been expected to win, but his margin — almost 30 points — was shocking. The key: Nearly 80 percent of black voters backed him. Clinton's hopes of faring respectably with African Americans were shot and the Obama coalition was set. It was just enough to win him the Democratic nomination.

What it means for Biden now: He's breathing a sigh of relief over this one, because it could have meant a lot, but right now it may not. At the outset of the campaign, it seemed possible that either Kamala Harris or Cory Booker (or both) would lock down significant black support, as Obama did early in the 2008 cycle, and that each would then be positioned to expand that backing rapidly with an Obama-like breakthrough in Iowa or New Hampshire. But Harris is now out of the race and Booker is running at three percent nationally with black voters. If Booker were to make a late move in Iowa, he could still pose a major threat to Biden's black support, but the clock is ticking.

In 2016, the story for Clinton was similar and even more emphatic. She entered as the clear national front-runner, but soon faced a surprisingly strong challenge from Sanders. As the national race tightened, a potential Clinton firewall emerged: polls showed black voters remained overwhelmingly behind her. But would that support hold if she lost the early states?

She nearly did in Iowa, barely edging out Sanders in a tight race that wasn't resolved until the morning after the caucuses. Then, she was trounced in New Hampshire by 22 points. But Clinton then pulled out a solid — eight points — victory in Nevada, and any sense of crisis had long since abated when the race reached South Carolina. There, Clinton dismantled Sanders, winning the black vote by an astounding 72 points, and the primary by 47 percentage points. It set the tone for the remainder of the race. Sanders was unable to puncture Clinton's black support in any meaningful way, and it proved key to her ability to secure the nomination.

What it means for Biden now: Clinton won Iowa in 2016 by a total of four "state delegate equivalents." (There was no popular vote reported, although there will be this time.) That's about as close as you can come to losing while still winning.

Now ask yourself: What if she'd done just a hair worse and actually lost Iowa? And then lost New Hampshire in a 22-point rout? What would have happened if Clinton lost both? How would it have played in the press? How would influential Democratic voices have treated it? Would she still have been able to turn around and win Nevada or would she have lost there, too? And if she'd lost there, would her South Carolina firewall still have held? Or would Sanders have made real inroads with black voters and altered the course of the Democratic race?

That's a lot of questions, but it's the great unknowable that makes 2016 so fascinating to look back at now. Clinton won the nomination handily, but she almost lost both Iowa and New Hampshire. If you believe her South Carolina support would have held despite earlier defeats, then you're probably bullish on Biden's chances of absorbing back-to-back losses to start the primary season (and maybe losing Nevada, too) and still winning the nomination. But if you're not so convinced, then the lesson could be ominous for Biden now.

3. National leader loses Iowa, New Hampshire

In 2004, Howard Dean was the front-runner coming into the early states but not an overwhelming one, and, unlike Biden, he was running as an insurgent. Dean's lopsided Iowa loss triggered a meltdown of his support elsewhere. He lost New Hampshire handily and every other state, except for his native Vermont.

But Dean's demise is not what makes 2004 worrisome for Biden. It's the rise of John Kerry that does.

Kerry's campaign began with high hopes — a decorated veteran seeking to challenge a wartime president. But by the end of 2003, he was languishing in single digits nationally and running far behind Dean in the early states. Kerry caught fire in the closing weeks in Iowa and, aided by some late attacks on Dean from another candidate, Richard Gephardt, surged to a victory with 38 percent. A week later, he won New Hampshire, where not long before he'd been trailing by more than 20 points.

Then it was on to the South, where Kerry faced a challenge. A December 2003 poll had shown him with just 1 percent support among black voters in South Carolina. But his twin victories in the lead-off states had transformed his standing. Democrats, eager to anoint a nominee and go after Bush, were flocking to him.

In South Carolina, Kerry ended up losing the black vote by just three points, while in other states, he won it outright. The candidate who'd barely been a blip with African American voters at the start of 2004 won a majority of them nationally in the Democratic primaries — and took the nomination with ease.

What it means for Biden: The rise of Kerry, who endorsed Biden last week, demonstrates the potentially transformative power of winning both early states — especially in a climate in which Democrats are hungry to unite. He was far from the first choice of black voters, and most white voters for that matter, but he was an acceptable choice. And when he won Iowa and New Hampshire, that was good enough.

This is the dread scenario for Biden: An opponent sweeps the first two states and Democrats elsewhere deem him or her an acceptable choice and climb on the bandwagon.