How scientists are trying to stop space debris from creating a cosmic junkyard.

Humans are a messy species. Not only are we polluting the air, land and water on Earth, but we’re leaving our litter in space too.

There are countless objects, known as space debris, orbiting above us. One of them, an abandoned Chinese space station, fell to earth on 2 April. The immediate risks posed to humans by the re-entry of objects like China’s Tiangong-1 (or “Heavenly Palace”’) are miniscule -- most debris burns up in the earth’s atmosphere and the chances of being hit by the remaining fragments are less than being struck by lightning.

But space debris poses other threats. Ranging from small flecks of paint to bus-sized defunct spacecraft, these objects can damage or destroy operational satellites that are essential to our modern lives. In the longer term, they could turn valuable orbits into big junkyards.

Euronews spoke to Tim Flohrer, a space debris expert at the European Space Agency, about what can be done to keep space clean and usable as a resource for future generations.

How much space debris is there and what is it?

Only a small amount of objects in space are satellites that we use: around 1,500, or maybe a bit more now as we’re seeing a rapid increase in access satellites. We have a catalogue, a list of all the elements of space debris, which includes more than 20,000 objects larger than 10 centimetres. About two-thirds of these are fragments resulting from explosions or collisions in space. We also have spacecraft used to bring satellites into orbit and once they are no longer useful, most of them, unfortunately, also stay in orbit. And we have something called mission-related objects, such as telescope covers, bolts and weights, that are released into orbit. If you look at smaller sizes, we have around 600,000 objects larger than one centimetre but smaller than 10 centimetres, which are still dangerous because they can damage or even destroy small satellites.

Some space debris has been described as “flying bullets.” Does this description apply to those smaller objects?

Yes, you can say that. You have to imagine the velocities are extremely high, at 7.5 kilometres per second with orbital velocity. In the case of a head-on approach for a collision, you would have up to 15 kilometres per second. A one centimetre object, then, can have an energy on collision that is comparable to an exploding hand grenade. Of course, you can imagine a satellite isn’t going to survive such a collision.

Why is it a problem to have all of these objects in space?

There are two quite different problems. The first one is a short-term problem. We operate satellites and in our daily life we rely on a lot of services from satellite infrastructure in space, such as navigation, telecommunication, better forecasts, and so on. In our daily operations, we have to consider the space debris population in order to safely operate all satellites. We have to conduct collision avoidance manoeuvres, and from time to time, we have re-entry events, when large objects enter the atmosphere and do not completely burn up.

The long-term problem is that the growth of the space debris population has reached a certain tipping point -- we describe it as having a “critical density” of objects in certain orbits. Already in the 70s, a researcher Donald Kessler predicted this would happen, and it’s called the Kessler Syndrome. It would mean that fragments generated out of space debris collisions in space create subsequent fragmentations or collisions. That would lead to an exponential growth of the space debris population in orbit, which in turn, would render some orbital regimes as not usable anymore, like the low Earth orbit [where most satellites are placed, including the International Space Station] or the geostationary orbit, which are very precious resources for continuing the utilisation of space for applications that are so central for life today.

How likely is it that the Kessler Syndrome will become a reality?

Unfortunately, it’s quite likely if we continue with what we call a business-as-usual scenario. In the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee, or the IADC, we have coordinated studies to predict the growth of the space debris population in orbit. The result of these studies was a consensus among the space agencies that even if we make progress in mitigating the creation of space debris -- even if we get better than the business-as-usual scenario -- we will still see a growth in the population, that is, the setting in of this Kessler Syndrome.

The conclusion of the agencies was that we need to take out massive objects from orbit, in particular, those massive objects that have the potential to fragment into smaller space debris particles.

What else can we do about space debris?

We have to increase our efforts in complying with space debris mitigation guidelines and rules that are there. We need to mitigate against the creation of new debris. There are several ways that we can do that: the most important one is to move objects out of these densely populated regions. In the lower Earth orbit regime, there’s a rule that within 25 years after the end of your mission you remove the satellite from orbit. In geostationary orbit, you should move the object to the so-called graveyard orbit and “passivate” your satellite at the end of a mission -- that means you remove all the sources of energy, you deplete fuel and you shortcut batteries so that the risk that it explodes is minimised. And there are some other rules as well.

The other point is to go and grab the heavy, massive objects and bring them to a controlled re-entry and burn up in the atmosphere. Unfortunately, simulations show that we have to do that for at least a few objects every year and, we have to say, the technology for that is under development but does not exist today.

Is everyone following the mitigation regulations?

There is a report (pdf) on compliance to the space debris mitigation guidelines that my colleagues published and it shows a quite interesting pattern. In the geostationary region, where you have a large amount of telecommunication and broadcasting satellites, nearly all of the operators at the end of their mission at least attempt to move out of the geostationary orbit -- so there is good progress there. The rules have been there for nearly two decades and they are now considered in the design and operation of satellites.

In the lower Earth regime, unfortunately we have to say that the majority are still relying on the atmosphere to wash out the objects. This is fine for up to say 500 or 600 kilometres, depending on the satellites -- it is sufficient to say that after 25 years these satellites will re-enter. But for higher orbits or more massive objects, the number of satellites that perform an active “deorbit burn” -- going down in altitude or even doing a controlled re-entry -- is still not growing, and that is a matter of concern. Particularly if we think of the future: with the announcement of large satellite constellations coming up, we can see that launching satellites into space is getting cheaper, satellites are smaller, and that means we have to increase our efforts to mitigate the creation of space debris.

As the access to space is getting cheaper and there are more services that can be provided, and also more customers -- which is a great thing, don’t get me wrong on that -- we have to reach out to more and more commercial operators and service providers relying on space as a resource. Some colleagues point to the “tragedy of the commons,” which is a concept also in other areas, where a certain resource that is shared can be overused if it’s not regulated well enough.

There are different schema and so-called industrial standards, and these are voluntary but they are followed by most of the operators. They are developed by agencies and industry together, so they are understood to be feasible in terms of what they require, but you can still decide not to follow a standard in your project. And there we hope that national legislation is compatible to these standards. Some countries do that and we hope that there is progress in that area.

What are some of the different options being explored to remove the debris that’s already in space?

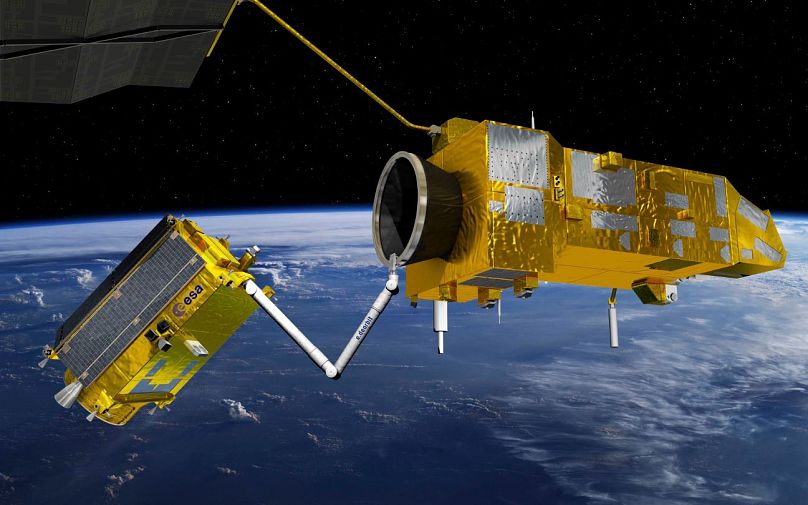

At the European Space Agency, there is the Clean Space initiative that my colleagues at the European Space Research and Technology Centre in the Netherlands are very active in. They have selected several technologies that need to be developed. We require an understanding of the tumbling behaviour of these objects to be removed -- how much they spin, on what axis, and so on. It’s not a trivial task, but you can do it from the ground, and we are developing the means to understand these objects that are not under control anymore.

Then you need to develop technologies to manoeuvre with your vehicle close to the object, and probably then, to make a closer inspection of the satellite to be removed.

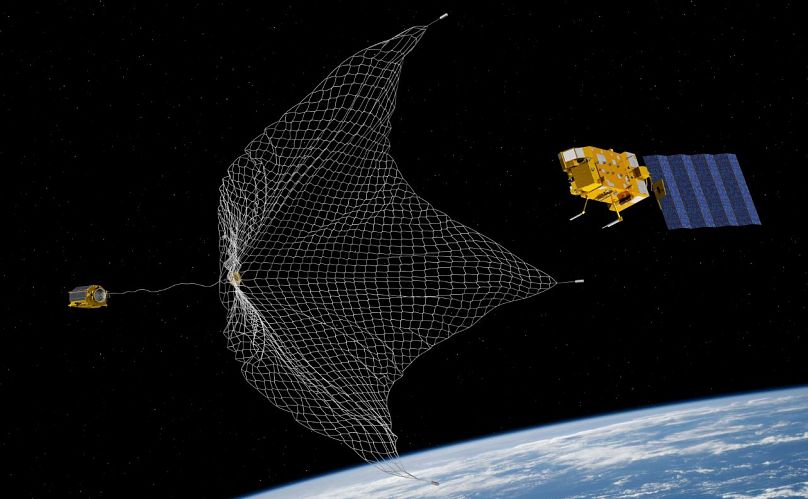

And you have to develop technologies to grab the object or somehow act on it so that it can be removed from orbit. There are several technologies that are being discussed -- some of them are robotic arms, some are nets, and even a harpoon has been proposed.

Can you say anything about who’s leading and who’s lagging in terms of using space sustainably?

Most of the players in space, if not all of them, have understood that it’s a global problem, and it requires cross-global approaches. It’s not that we can fingerpoint to somebody. It’s really understood as a common risk for all of us. Some are more advanced, of course, but all take efforts to avoid the creation of space debris. I think this is already good news that it’s understood and shared.

We should understand that space is a resource and in daily life many people use space technologies without being aware of it. That’s perfectly fine, but we should maybe take a minute to imagine how our daily lives would be without space applications.

Tim Flohrer is a Space Debris Analyst at the European Space Agency. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Opinions expressed in View articles are not those of Euronews.