A young Chechen man in Vienna set up a TikTok channel with a police officer to answer questions most immigrants are too scared to ask, plus some silly ones too.

Young Achmad Mitaev is fed up with Austrian police being racist towards immigrants.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The 23-year-old wants to prove that the Chechen community he belongs to — often victims of some of the worst prejudices in Europe — can also play a constructive role in their societies.

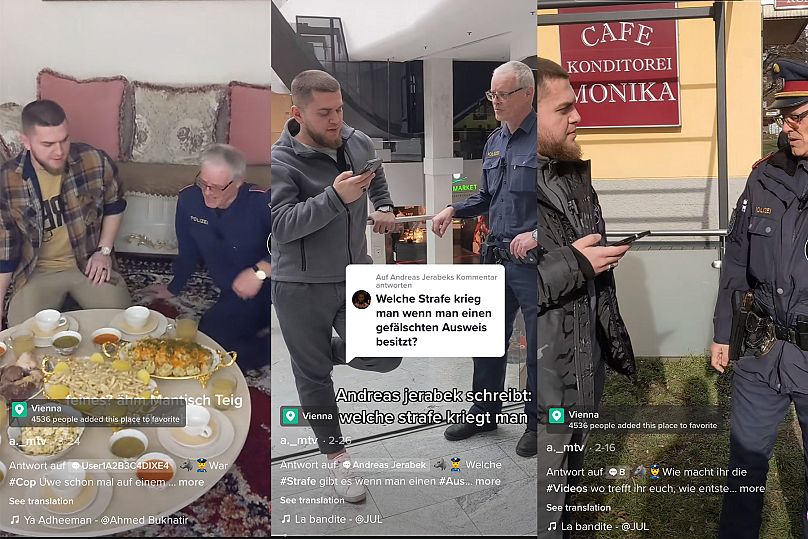

His TikTok account, dubbed 'The Chechen and the Cop', encourages people to ask the police even the most bizarre questions — such as "What would happen if I tried to smuggle my cousin into Europe?" or "What should I do when I see a police handgun on the street?"

From cruelty in Chechnya to abuse in Austria

Mitaev and his family fled their native Chechnya more than a decade ago on a perilous journey lasting months, first ending up in Poland and then in Austria.

Chechnya is a Russian republic that was forced to remain under Moscow's control after the Soviet Union collapsed. Its population are subjected to harsh human rights abuses.

People can be abrasive towards the Chechen community since they associate them with figures like Ramzan Kadyrov, the notorious leader of Chechnya and a loyal ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

In turn, Chechen soldiers have been deployed directly to the frontline in Ukraine by the Kremlin, though a small number are fighting on the other side too.

“My mum, my dad and my siblings were on the road for three months fleeing from Russia, where the police is extremely cruel and unfair. So I definitely didn’t expect the police treatment I received in Austria,” he told Euronews.

He lives in Vienna's 20th district, an eclectic multicultural neighbourhood located along the Danube Canal.

Home to a high number of immigrant communities, police often patrol the area and stop people they deem suspicious — a practice long criticised as problematic throughout Europe and the US.

At 14, Mitaev became one of the youngest inmates in Austria after being arrested for resisting what he says was the third stop-and-search that day.

“The police are allowed to stop and check you over at any given point and without providing any reason for it. The Chechen community, in particular, gets stopped a lot,” he recalled.

“I kept being stopped on my way to work or school, and once I was stopped by the same policeman three different times and I reacted to that.”

Years later, the police invited him and some other people from the community to brainstorm ways in which law enforcement could be more approachable. They suggested the youngsters play football with the police or organise chess tournaments, which frustrated Mitaev.

“At one point I got sick of the conversation and told them, 'you guys are here because of us and you have no idea what we want,'” he said.

Uwe Schaffer, the 59-year-old policeman who later became the protagonist of Mitaev’s TikTok videos, exchanged phone numbers with the young man and asked to meet up separately to discuss other options.

This is how the idea for the channel was born.

“The other policemen told Uwe that he was crazy, making videos with these Chechens. They told him they’re all criminals anyway. He didn’t listen to them and said he was committed to doing it no matter what.”

'Police should not shy away from women with headscarves'

The format is relatively straightforward. Mitaev meets up with Schaffer somewhere in Vienna, like in a mall or in a public space. The young Chechen reads him a question from a user, and the police officer responds — often with brutal honesty.

For example, one of the questions involved the ban on face coverings in Vienna. While respect for religious communities is enshrined in the Austrian constitution, there is a ban on full-face coverings. Certain Muslim religious head coverings — such as the niqab — are therefore banned, explains Schaffer.

“But what about when someone covers up their mouth because they’re wearing a face mask? Like, for COVID?” Mitaev asks. Schaffer replies the police have a hard time distinguishing between the two, and that he would advise people to not wear headscarves instead of masks.

Austria is home to some voracious right-wing and hard-right parties, who base a large part of their rhetoric on spreading fear of immigrants — especially Muslims — among the majority Austrian population.

For Mitaev, the goal of his project is to tear down the walls between the police and those who fear them the most.

“For example, women who wear a headscarf or who do not speak perfect German don’t feel free to just ask the police about something, so they send me questions on my TikTok.”

'Immigrants should be eternally grateful, and not commit crimes'

Kenan Dogan Güngör is the founder of "Think Difference", an organisation focused on overcoming integration issues and consulting on questions of diversity.

He says that while certain crimes “do indeed occur more frequently in certain migrant groups,” the lack of tolerance towards these groups also “triggers a higher level of outrage”.

Public outrage, he told Euronews, is “sparked not just by the crime, but also the person who committed it … the errors, grievances towards and even the criminality of unwanted and devalued groups and minorities are often perceived more strongly,” as a means of “confirming their reservations and prejudices”.

Majority communities in many European countries “expect humility and gratitude from migrants, refugees and perceived outsiders. Offences committed by these groups are seen as a particular violation of this expectation, and accordingly, the indignation is higher, more dramatised and instrumentalised by politics and the media.”

Mitaev says one of the basic problems these communities face is not understanding the rights they are entitled to.

“My main aim is to make sure people know their rights in the country they live in. People need to know what can happen to them in certain situations.”

He jokes that some of his friends first accused him of being a police informant, before becoming fans of his videos.

“It should also tell people not to hate law enforcement officers in uniform, and that you should not distance yourself from them completely.”