It's been ten years since a street vendor set himself on fire to protest against rising living costs and corruption in Tunisia, sparking the Arab Spring.

A Tunisian parliamentarian is seen approaching crowds with his car as demonstrators block the entrance of the capital’s parliament building in a video posted to social media on December 8th.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

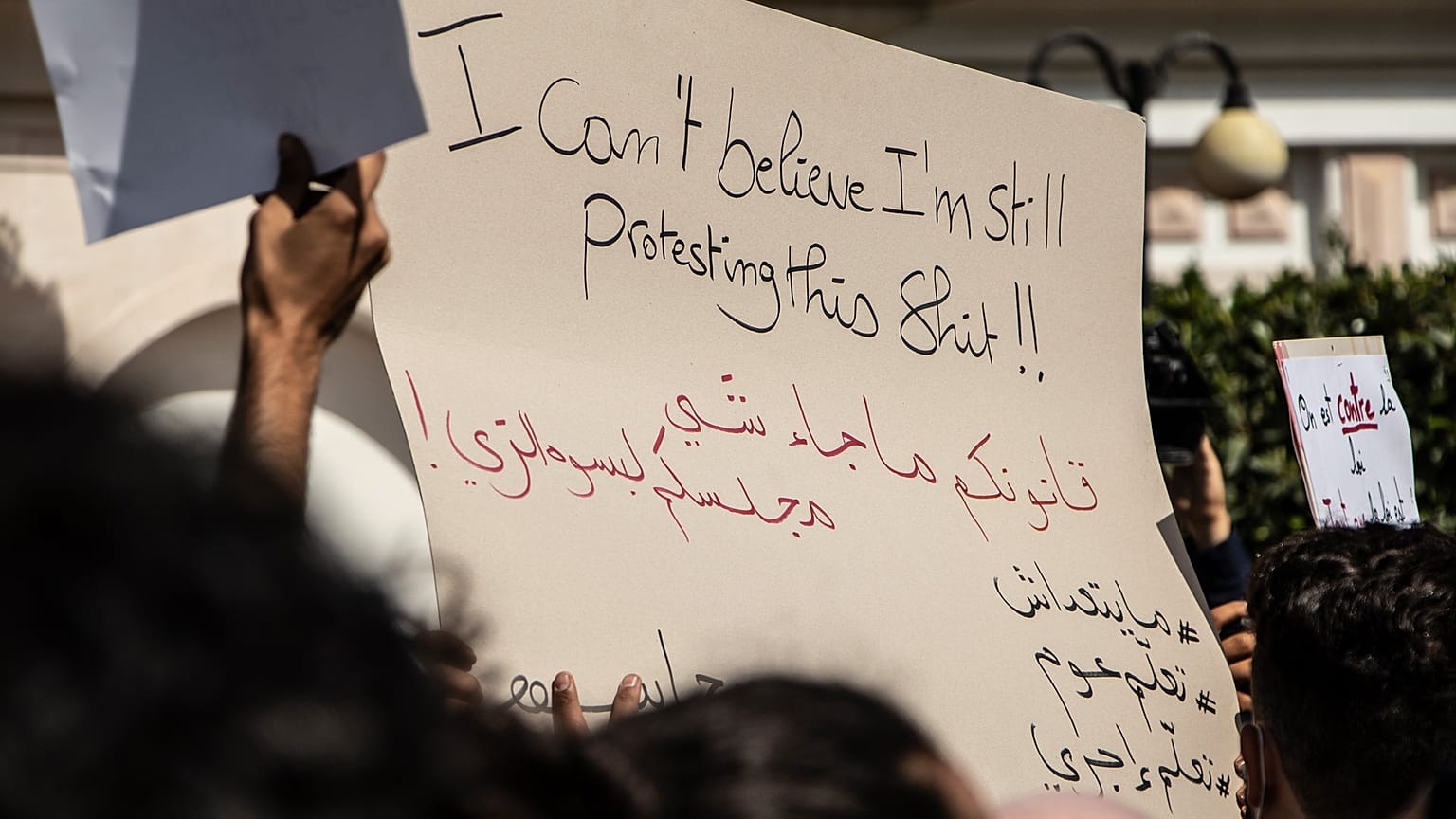

The activists were protesting comments made a few days earlier by Mohamed Affas, a member of Tunisia's populist Dignity Coalition, who stated that “single mothers are either prostitutes or rape victims” and who targeted women and LGBTQ+ people.

Saif Ayadi claims he was one of the demonstrators who banged on the hood of the government official’s vehicle in an attempt to stop the physical assault on protesters.

The 23-year-old said he was then detained by police for damaging property, and held for two days. He is still awaiting his trial.

Oussama Sghaier, a member of Tunisia's parliament, showed his damaged car in a Facebook live video and equated the protesters to IS extremists in front of the country’s ministry of interior. Ayadi is being apprehended by authorities in the background.

"This moral and physical aggression is common from them," said Ayadi, who is a social worker at Damj, a Tunis-based LGBT rights group. Yet in recent years, he added, it has translated to social and online media.

He claims that during October protests that NGO members took part in this year, authorities used surveillance and digital platforms to not only identify and silence protesters but to shame them publicly or find evidence of them criticising the government.

In addition to Ayadi’s Facebook profile and email being temporarily de-activated on October 5th before the demonstrations took place, he alleges that government forces took photos of gay and transgender protesters and posted them on their official social media platforms along with personal information such as their full name and home address.

"They would expose their sexual orientation and gender expression to defame them and expose them to danger," says the activist.

Euronews has reached out to the Tunisian Assembly of the Representatives of the People inquiring about these claims, but they had not responded at the time of publication.

Freedom of expression?

Tunisia is considered to be one of the few countries, if not the only one, to have made significant reforms following the Arab Spring, which was ignited exactly a decade ago in Tunisia on December 17th, 2010.

The country has improved on freedom of speech laws since then, by, for example, adding Article 31 of Tunisia’s 2014 constitution, which allows people to criticise government entities and policies.

But, according to Al Bawsala, a politically independent NGO with the goal of promoting good governance, Tunisia has yet to develop their digital policies, however.

“There are no laws in Tunisia that incriminate electronic crimes,” says Seif Ben Tili, a project manager at the organisation, adding that there are no laws about digital surveillance.

He says that before the Arab Spring, he could not use YouTube without a VPN, so even though a lot has changed, there is still a need for major reform.

While the previous Ben Ali-era laws of restricted expression have not returned, an Amnesty International report states in the past two years, authorities have demonstrated “increasing intolerance towards those who criticise public officials or institutions” after examining the cases of 40 bloggers, online activists, and administrators of Facebook pages who have been targeted by authorities.

In October 2019, the Tunisian Ministry of Interior issued a statement which said it would “take legal action against those who intentionally offend, question, or attribute false allegations to its departments.”

And this year the country’s police union issued a statement on its official Facebook page instructing people on how to submit complaints against people who have “insulted, provoked, or verbally assaulted security forces.”

This took place after protests in early October in response to the Tunisian parliament proposing legislation that would reinforce impunity for security forces and protect them from any criminal responsibility.

Encrypted activism

Some activist groups say they have found safe, and hidden, digital spaces to congregate and organise in an attempt to evade authorities.

A member of the Wrong Generation group, a Tunisian anti-fascist movement which believes the current government is an oligarchical police state, says that they are using gaming communication platforms to organise, create protest content such as memes, and warn each another of government surveillance attempts and methods.

Using the username Zapata, a homage to early 20th century Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata, the digital organiser says that their nearly 300-member community is able to "safely" host weekly public meetings.

Zapata cites that other groups are also using end-to-end encryption networks such as Element to have secure conversations.

“Until now authority surveillance is incapable of tracking our use of encrypted platforms,” says the young user, who says he’ll continue to organise in this way until digital freedoms improve in Tunisia.

_Molka Bouzouraa contributed to this report. _