By Zeba Siddiqui

NEW DELHI (Reuters) - For over a decade Arvind Singh has worked as a watchman in New Delhi, doing the rounds of the streets with a whistle and a wooden stick to keep vigil at night.

Watchmen like him are so ubiquitous in India, guarding everything from offices to homes and stores to factories, that their presence goes almost unnoticed. But over the past week, the watchman has dominated India's headlines.

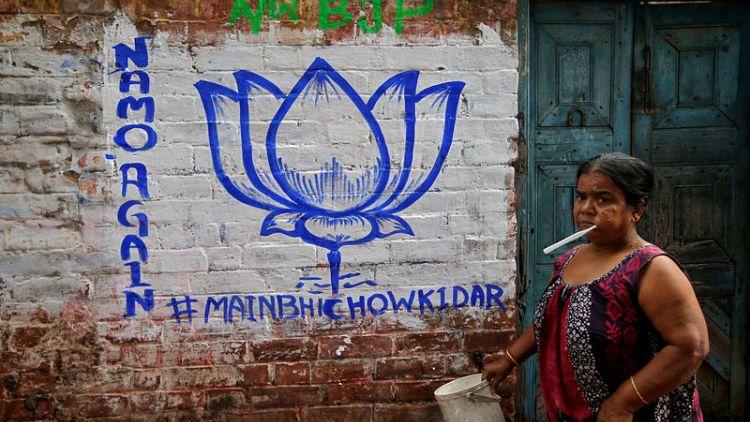

That's because the latest campaign to be launched this week by Prime Minister Narendra Modi just before a general election beginning on April 11 is the "Main bhi chowkidar" or "I am also a watchman" campaign.

He tied an appeal to tens of millions of often poorly paid watchmen to the priorities of his own job, following a suicide bomb attack that killed 40 paramilitary policemen in the northern region of Kashmir last month.

"We both work day and night. You guard homes and I guard the nation," Modi said in an audio speech addressed to watchmen on Wednesday.

"The watchman has become a symbol of the country’s nationalism,” he said, equating everyone from teachers and doctors to watchmen guarding the country in their own way.

The campaign came in response to the opposition Congress party’s slogan "chowkidar chor hai", or the nation's "watchman is a thief", which it began using late last year to refer to Modi in connection with allegations of irregularities in the awarding of a defence contract. Modi has denied any wrongdoing.

In recent days, leaders and supporters of Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) have launched a coordinated effort to popularize his watchman campaign, with many changing their social media names to add the prefix ‘chowkidar’.

But for many watchmen, who are among the millions in India’s vast informal economy where workers are often poorly paid and barely protected by labour laws, Modi’s campaign is a political gimmick that is unlikely to improve their lives.

"I don’t know why they started it," said Rakesh Yadav, a 37-year-old watchman from India's most populous state of Uttar Pradesh.

"In the last four years they have done nothing for us,” he said, looking up from a newspaper while on duty outside a residential complex in New Delhi.

“If PM was a chowkidar, would Nirav Modi run away?” said another watchman, Mohammed Nayyar, referring to a billionaire jeweller who fled to Britain last year before an alleged $2 billion loan fraud he is accused of being involved in came to light. The jeweller is not related to the prime minister.

The cash-based economy suffered a serious hit from the Modi government’s shock move to ban high-value currency notes in 2016.

'DONE A LOT'

Singh remembers being unable to feed his children for some days and standing in long queues at the banks to exchange the voided currency for new notes.

“What has changed in our lives? We are doing the same duty we were doing some years ago,” he said, adding that his salary had not increased from about $130 a month in three years.

The chowkidar campaign is a distinct reminder of Modi’s 2014 “chaiwallah” campaign in which he flaunted his past working for his father as a chaiwallah, or tea vendor.

It may be a gimmick, but such things have worked for Modi in the past, said Priyavadan Patel, a veteran political scientist from Modi’s home state of Gujarat and scholar at the Lokniti research programme of Delhi's Centre for the Study of Developing Societies.

“The chaiwalla campaign worked in a big way,” Patel said.

Such connections with the common man helped the BJP to gain a big parliamentary majority, the likes of which had not been seen in three decades in India, in 2014.

But that’s unlikely to be repeated this time.

Polls predict Modi might win a second term but with a much smaller majority, amid concerns about a lack of jobs growth and millions of farmers dissatisfied over depressed crop prices.

Some of the most challenging battleground states for Modi's party are those that depend on the farm economy. “The chowkidar campaign may not work in such areas,” Patel said.

One of those states is Bihar, where the watchman Singh migrated from 12 years ago. He said he wouldn’t go back because working on the farm back home was not profitable.

Yet, he said he believes in Modi, and praised him for air strikes on neighbouring Pakistan in response to last month’s bomb attack.

“I feel like Modi ji has done a lot,” he said, using a suffix that denotes respect. “And I think he will do a lot more in the coming years."

(Edited by Martin Howell, Robert Birsel)