Behind the scenes at the Canadian Space Agency to meet the team that controls the Canadarm 2, trains astronauts to use space robots, and develops rovers for the Moon and Mars.

Robots are an essential companion to mankind in space, and many of the modern-day masters of these robots are to be found in Montreal, home to the Canadian Space Agency.

Euronews Space has unique access to the team, among them operations engineer Mathieu Caron, who can steer the Canadarm 2 directly from his control room, or instruct astronauts piloting it in space.

When we meet him, he is preparing for a tricky manoeuvre.

“In a few months we’ll be using the Canadarm2 to catch a Dragon resupply capsule,” Caron tells Euronews. “That capsule cannot dock on its own with the space station. It matches the heading and speed of the space station, comes within ten metres of the station, and the astronauts inside will use the Canadarm 2 to grab on to the Space X capsule.”

That process has to be ultra-precise, but also speedy: “They have to make sure that they grab on quickly, otherwise a small perturbation will cause the vehicle to diverge quite rapidly.”

Canada – which has partnered with the European Space Agency since the 1970s – launched its first Canadarm space robot on the American shuttle back in 1981.

“It was a request from NASA to build an arm for the space shuttle, which was then designed and built in Canada,” says Stéphane Desjardins, Acting Director of Space Exploration. “Then, from then on, each Shuttle had its space arm, which was used for most of their missions. Afterwards, when it was time to design the ISS, Canada proposed making a new arm, the Canadarm 2, for the space station.”

That arm, and Dextre, the mobile servicing robot, are a lasting source of satisfaction for the country, which even features the Canadarm and its Dextre ‘robotic hand’ on its five dollar notes. As Canada’s best-known astronaut Chris Hadfield says: “Canada built the Canadarm 2, and Canadarm 2 built this space station. Everybody should be proud of that.”

The CSA works with many international partners, and each and every ESA and NASA astronaut has to train on Canadian space robotics.

It begins with a scale model of the ISS and a lesson from engineer Kumudu Jinadasa, who uses the model to help the astronauts orientate themselves around the orbiting space laboratory.

She asks them to use the mini Canadarm model and “configure each of the joints – roll, yaw, pitch – then they’ll put it in the initial configuration for their operation, and they’ll actually put it on the station, and go through the motion of the arm to the operation that they’re going to do.”

“It’s important because we don’t want any collisions in space. Either self-collisions between the robotics themselves, self-collisions between the joints, collisions with EVA, that would be catastrophic, or even collisions with the station, which could cause a rapid de-press and then we’d be in a really high emergency situation,” says Jinadasa.

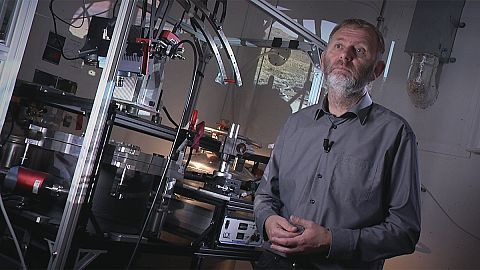

While the daily operations of Canadarm continue, CSA engineers are also working on robot rovers for the Moon and Mars.

Director of Space Science and Technology Jean-Claude Piedboeuf shows Euronews one of the recent designs: “The aim is to see if we can send rovers for planetary exploration. So we’re aiming for the Moon and Mars. So you have to find wheels that can adapt and resist the cold – it can be minus 150, minus 200 degrees (Celsius) – so rubber wheels don’t work, you have to be able to adapt to obstacles and be really tough.”

The long-term vision is that such rovers would be mounted with drills and prospection devices to search for useful resources that could help mankind survive in space.

Piedboeuf explains: “If we were able to find water on the Moon, that would allow us to use the Moon as a base, make fuel, make oxygen. So if we had water, and we’ve shown that there are traces of it there, then the next step is to show if we’re capable of extracting water and be able to do something with it with sufficient quantities.”

“So that’s a type of mission that we could do, that would then allow us to pursue lunar exploration.”

The history of space robotics has been one of man and machine working hand in hand, but the future is likely to be one of autonomy, as robots work remotely, saving astronauts from hazardous tasks.

Mathieu Caron sets out the vision for the near future: “Whenever something can be done robotically, we’re asked to do so. I’m talking about cutting or moving thermal blankets, unscrewing caps, cutting tethers, even bringing a nozzle and pumping fuel in the satellite.”

Longer term, Canada and the other ISS partners are looking beyond near Earth orbit, to a station deeper in space.

“The next step will be to go further,” Desjardins tells Euronews. “We talk about a cislunar station, in the space between the Earth and Moon. And there again, if we construct a space station habitat in that area, it’s sure and certain that we’re going to need space robotics.”