The latest State of the Global Climate report shows a planet on the brink, warns UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres.

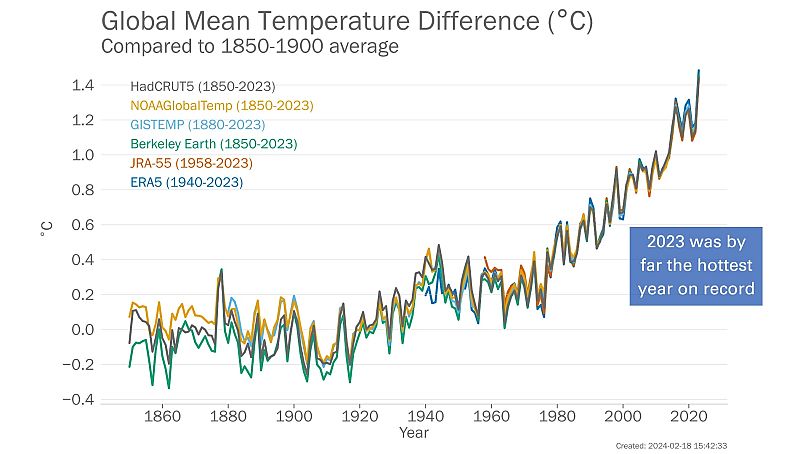

We already know that 2023 was the hottest year on record by a significant margin. But a new report from the UN’s meteorological agency reveals how many other symptoms of climate change were off the charts last year.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

“Climate change is about much more than temperatures,” says the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO)’s secretary-general Celeste Saulo. “What we witnessed in 2023, especially with the unprecedented ocean warmth, glacier retreat and Antarctic sea ice loss, is cause for particular concern.”

The WMO’s latest State of the Global Climate report takes stock of numerous indicators of the climate crisis, as well as their disastrous impacts on people in the form of heatwaves, floods, droughts, wildfires and rapidly intensifying tropical cyclones.

“Sirens are blaring across all major indicators,” comments UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres. “Some records aren’t just chart-topping, they’re chart-busting. And changes are speeding-up.”

Released today (19 March), it confirms that last year was record-breakingly hot; with global average near-surface temperatures reaching 1.45°C above pre-industrial levels.

“Never have we been so close - albeit on a temporary basis at the moment - to the 1.5°C lower limit of the Paris Agreement on climate change,” says Saulo. “The WMO community is sounding the Red Alert to the world.”

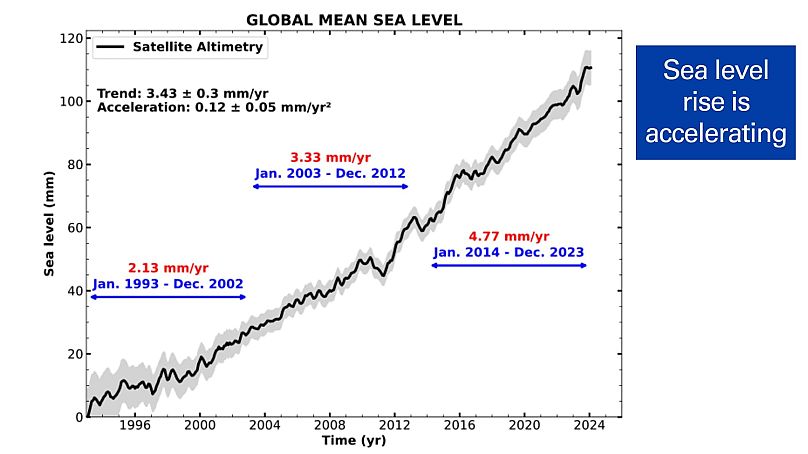

How much have sea levels risen?

In 2023, the world’s global mean sea level hit a new high in the satellite record, which dates back to 1993.

Sea levels have crept up by 3.34mm per year on average over the last 30 years. And as the chart below shows, the rate of sea level rise has been increasing. It more than doubled from 2.13 mm/year between 1993 to 2002 to 4.77 mm/year from 2014 to 2023.

This is down to continued ocean heating - which causes water to expand - as well as the melting of glaciers and ice sheets.

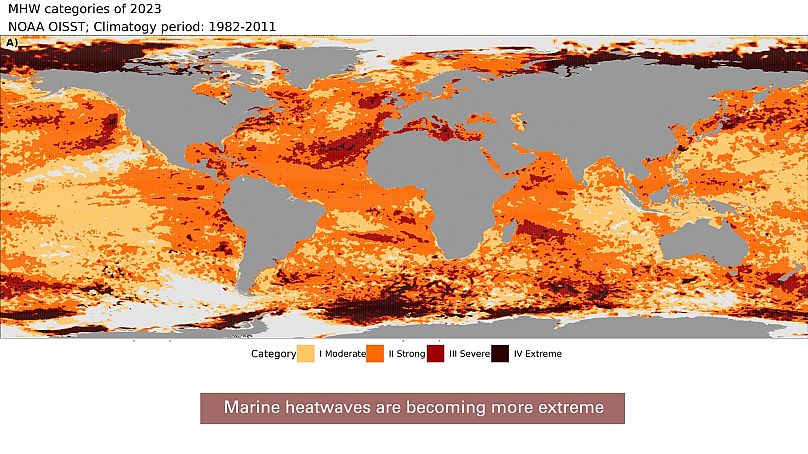

How much have the world’s oceans heated by?

Ocean heat reached its highest level last year in the 65-year observational record.

The shift from La Niña to El Niño conditions in the middle of 2023 contributed to the rapid rise in temperature, felt both on land and in water.

But the typical patterns of warming associated with the weather phenomenon - i.e. Pacific Ocean warming - do not explain other areas of unusual heating such as in the Northeast Atlantic.

This body of ocean suffered widespread marine heatwaves from spring onwards, peaking in September and persisting to the end of the year, when temperatures were 3°C above average.

On an average day in 2023, nearly one-third of the global ocean was gripped by a marine heatwave, harming marine ecosystems and coral reefs. Towards the end of the year, over 90 per cent of the ocean had experienced heatwave conditions at some point.

Global average sea-surface temperatures (SSTs) were at a record high from April onwards. And the WMO experts expect that warming will continue in 2024 - a change which is irreversible on scales of hundreds to thousands of years.

Antarctic sea ice and glacier records broken

Records were smashed in the cryosphere, too.

Antarctic sea ice extent (the total area covered by at least 15 per cent ice concentration) was by far the lowest on record last year. At the end of winter, it was 1 million square kilometres below the previous record year - an area equivalent to France and Germany combined.

What scientists refer to as the global ‘reference’ glaciers - those which have been monitored long enough to measure climate-related changes - also underwent their largest loss of ice on record (since 1950). This was driven by extreme melt in North America and Europe.

Glaciers in the European Alps suffered an extreme melt season. In Switzerland, glaciers have lost around 10 per cent of their remaining volume in the past two years, the report reveals.

“The world's ice cover, on land and floating at sea, provides a major service to our climate by reflecting solar energy back to space and storing water that would otherwise flood our coasts,” says Professor Martin Siegert, a polar expert at the University of Exeter.

Unpacking the significance of these blows to our frozen planet, he adds that, “The world will feel the detrimental effects now and into the future because the changes observed will lead to 'feedback' processes encouraging further change.

“Our only response must be to stop burning fossil fuels so that the damage can be limited. That is our best and only option.”

Greenhouse gas concentrations reached record-high levels

The long-term increase in global temperature is due to increased concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere - largely down to the burning of fossil fuels.

Concentrations of the three main greenhouse gases - carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide - reached record levels in 2022. Real-time data from specific locations show a continued increase in 2023, according to WMO’s report.

CO2 levels are 50 per cent higher than in the pre-industrial era, trapping heat in the atmosphere.

“The climate crisis is THE defining challenge that humanity faces and is closely intertwined with the inequality crisis - as witnessed by growing food insecurity and population displacement, and biodiversity loss,” says Saulo.

After a calendar of extreme weather events, what hope is there for the future?

WMO’s report also sets out in glaring detail the extreme weather events that hammered the globe last year. Extreme heat scorched southern Europe in July, with temperatures in Italy reaching 48.2C.

In September, flooding linked to extreme rainfall from Mediterranean Cyclone Daniel affected Greece, Bulgaria, Türkiye, and Libya with thousands of people killed in Libya.

Extreme weather and climate hazards exacerbated challenges for many vulnerable populations around the world, continuing to trigger food insecurity and displacement.

Yet the report exposes a large climate financing gap.

To stick to 1.5°C, annual climate finance investments need to grow more than six-fold, reaching almost $9 trillion (€8.3 trillion) by 2030 and a further $10 trillion (€9.2 trillion) through to 2050.

The cost of inaction is far higher, however. Under a business-as-usual scenario, climate change could accumulate at least $1,266 trillion (€1,166 trillion) worth of damage between 2025-2100.

That should spur the world to take action, WMO suggests. And the experts find “a glimmer of hope” in the speed of the renewable energy transition.

In 2023, renewable capacity additions increased by almost 50 per cent from 2022, for a total of 510 gigawatts (GW) - the highest rate observed in the past two decades.