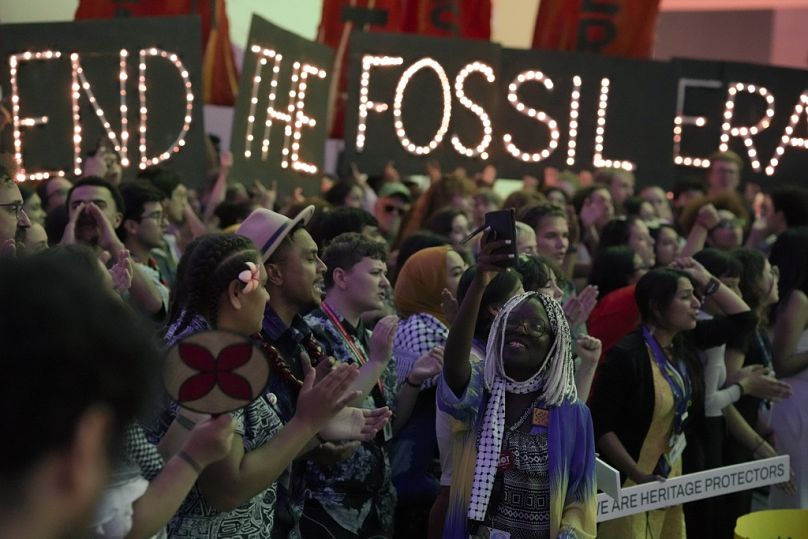

The various milestones agreed so far at COP28 are far from everything we need — but they’ll play a key role in shifting energy markets into a new gear under the realisation that the demise of the age of oil can be accelerated or delayed, but is ultimately unstoppable, Dr Nafeez Ahmed writes.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The UN chief, Antonio Guterres, has said that if COP28 does not reach a consensus to phase out fossil fuels, it will not be a success.

His comments came as Saudi Arabia rejected the UAE COP28 presidency’s position on a "phase down" of fossil fuels — which has also been resisted by other major oil producers in OPEC, including Iran and Iraq, as well as China, India and Russia.

Meanwhile, seemingly on the other side are the US, UK and EU governments which are now signalling their support for a fossil fuel phase-out.

But this seemingly irreconcilable dichotomy highlights a fundamental flaw in the debate.

We cannot phase out fossil fuels without phasing in a new energy system. And that requires committing to the hard work of changing our own energy systems, here and now.

A simple contradiction at the heart of failure

The landmark goal of tripling renewable energy production worldwide by 2030 will not be sufficient to replace the entire global fossil fuel system — but only to take out a significant chunk of oil demand.

Many experts have forgotten that without a clear timeline for the ramp-up to a 100% new clean energy system, it’s impossible to justify committing to a similar timeline for dismantling the incumbent system.

This simple contradiction lies at the heart of the failure of the global movement demanding a fossil fuel phase-out to convince 198 governments at COP28 — especially the 98 of them that are oil producers, half of whom of course are developing countries. It also exposes the futility of the current approach.

The simple fact is that to completely phase out fossil fuels, the world has to fully stop buying them.

And that means committing to building out completely new 100% post-carbon energy and economic systems: no one demanding a phase-out has made such necessary commitments.

Saying one thing and doing another

Rather, some of the loudest proponents of a phase-out are the biggest consumers of oil. John Kerry — US President Joe Biden’s special envoy on climate change — has supported phasing out fossil fuels. Yet, the US remains the largest consumer and producer of oil in the world.

Germany is backing a phase-out at COP28, but in the meantime is the world’s 11th largest oil consumer. France and the UK have also jumped on the phase-out bandwagon, despite being the 14th and 15th largest buyers of oil in the world.

Oil companies in the US and Europe are planning some of the biggest investments in oil and gas while their governments pontificate about a phase-out at COP28. And the US, Germany, Italy, Netherlands and Switzerland are spending billions in public subsidies to support fossil projects abroad.

Even worse, despite being the loudest voices on a phase-out, the US, UK and EU governments have refused to cough up the vast scale of climate finance needed to support poorer countries to transition away from oil, gas and coal to new energy systems.

Instead of unlocking trillions, Washington is blocking adaptation funding for the world’s most vulnerable.

Is there a silver lining?

But this doesn’t mean all is lost, and the UN chief is wrong to suggest COP28 is a failure without a phase-out agreement.

The COP28 presidency has already secured unprecedented support from 130 governments for its Global Declaration on tripling renewables and doubling energy efficiency by 2030.

This declaration sends an unmistakable signal to global energy markets. It will lead solar, wind and battery costs — already more competitive than fossil fuels in most regions of the world — to plummet by 50% by 2030.

And this, in turn, will increase their competitiveness, dramatically accelerating their deployment far beyond the tripling target.

Ramping up renewables has been the biggest driver of the disruption of fossil fuels in Europe. This means that this will, whether Saudi Arabia and others like it or not, accelerate a phase-down of fossil fuels, by extinguishing a huge chunk of global fossil fuel demand by 2030.

How fast can we build the post-carbon system?

As the fossil fuel system is already dependent on multi-trillion dollar direct and indirect subsidies, without which many companies are technically bankrupt, a large dent in demand will therefore strike an economic blow that leads many to extinction, incentivising investors to flee new fossil fuel investments.

These dynamics will dramatically amplify both the phase-out of fossil fuels and the phase-up of the new system.

As the emerging clean energy system experiences accelerated deployment, the fossil fuel system will enter accelerated decline. As that happens, everyone who consumes fossil fuels will need to look at deep social, economic and cultural transformations to support the phase-up.

The various milestones agreed so far at COP28 are far from everything we need — but they’ll play a key role in shifting energy markets into a new gear under the realisation that the demise of the age of oil can be accelerated or delayed, but is ultimately unstoppable.

The focus, now, has to be not on what we’re leaving behind — but on how fast we can build the emerging post-carbon system.

Dr Nafeez Ahmed is a systems theorist and futurist. He is Director of the System Shift Lab, Commissioner on the Transformational Economics Commission of the Club of Rome, and Distinguished Fellow at the Schumacher Institute for Sustainable Systems. He is the author of "Failing States, Collapsing Systems" and several other books on global systems.

At Euronews, we believe all views matter. Contact us at view@euronews.com to send pitches or submissions and be part of the conversation.