Noise pollution in our oceans is increasing. To investigate its consequences and possible solutions, we go back in time to September 2002, when a tragic event changed underwater noise research forever. Watch our report by clicking on the video above.

Antonio Fernández doesn’t have an ordinary job. He is a specialist in veterinary pathology, which means he has the important task of finding out the reasons behind animal deaths.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

“These can be dogs, cats, cows, horses, fishes, or even marine mammals, such as cetaceans,” explains Fernández, who is also a professor at the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria.

On 24 September 2002, his career took a huge turn.

“Early in the morning, we received a call from the Canary Islands government, saying that there were dead whales on the beaches of Fuerteventura,” he told Euronews.

More than ten beaked whales had stranded on the islands of Lanzarote and Fuerteventura, coinciding with a naval exercise conducted by NATO and Spanish ships in the area.

Some hours before, military boats had activated their mid-frequency, high-intensity sonars, a system used to detect underwater objects and enemy submarines.

“Are the military killing the whales?”, the government asked Fernández.

“My answer as a scientist was that we, scientists, never answer the who. We can answer the what, the how and the why of the death of animals, but never the who,” he replied.

Different types of marine mammals, such as sperm whales, pilot whales, and beaked whales, inhabit the waters surrounding the Canary Islands. The scientists and authorities wanted to know why all the beached animals were beaked whales from the Ziphidae family.

Fernández and his team quickly set about finding the cause of the cetaceans' deaths. But what they didn’t know is that their investigation would forever change the way we understand the effects of ocean noise.

“The reality is that we were going into a very sensitive field and issue, both socially and even politically,” says Fernández.

Finding out the what, how, and why of the whales’ deaths

The scientists from the Canary Islands found that the beaked whales had died of internal bleeding, and the cause appeared to be bubbles found in their brains, hearts and blood vessels.

“The scientific term is a gas embolism,” explains Fernández.

These tiny bubbles in cetaceans were a big discovery: they were similar to the ones that human divers develop if they rise to the surface too quickly.

This condition, often referred to as decompression sickness or ‘the bends’, can be fatal if divers are not treated immediately.

“We were breaking a dogma because it was assumed that if beaked whales [as cetaceans] had evolved over 60 million years to be the best divers in the ocean, it was not possible for them to suffer [from] that diving disease,” he says.

Fernández explains that because beaked whales dive at great depths, they accumulate a high concentration of nitrogen in their tissues, which is also a risk factor for gas embolisms.

Fernández’s hypothesis is that, when the beaked whales started hearing the sonar, they panicked and tried to escape, breaking their diving profile.

“When they start hearing ‘Pin, pin…’ they try to escape. But they hear it again from another direction. And another direction [...] They panic and try to escape at a speed and in conditions that their diving profile prevents them from [doing safely].”

In 2003, the specialists in veterinary pathology published their findings in the prestigious journal Nature. But this was met with doubts within the scientific community.

The study was discussed during a Marine Mammal Commission organised in the American city of Baltimore. Fernández and his colleague Paul Jepson had to present and defend their findings to scientists from all over the world.

During the gathering, English researcher Dr. Peter Tyack revealed something that wasn’t known until then. Beaked whales have a very characteristic diving profile, and that helped to explain why all the beached animals were from the same family.

This species takes about 30 per cent longer to surface than pilot whales and sperm whales, and they also have an astonishing habit. Just like human divers, they decompress when travelling upwards towards the surface, descending and rising again.

“After the presentations, many looked around and said: ‘Looks like these guys from the Canary Islands, who are not even on the map, could be right’”.

A ban on military sonar in the Canary Islands, but not in the rest of the world

Although this was not the first time a mass stranding had occurred in the world, what happened in the Canary Islands was a turning point.

The European Parliament adopted a non-binding resolution calling on member states to control and restrict the use of high-intensity sonar.

In 2004, Spain banned its use in Canary waters.

Fernández says: “There's a lot of science that justifies political decision-making, but it never gets there. In this case, I think there was an alignment of planets”.

Yet military sonar is still used all over the world today. And it is only one of the reasons for increasing noise pollution in our oceans.

Ocean noise, a growing threat to marine life

Between 2014 and 2019, underwater noise emissions doubled in European waters.

“The ocean is not a peaceful place anymore. There are so many activities taking place there,” says Nicolas Entrup, the director of international relations at the marine conservation organisation OceanCare.

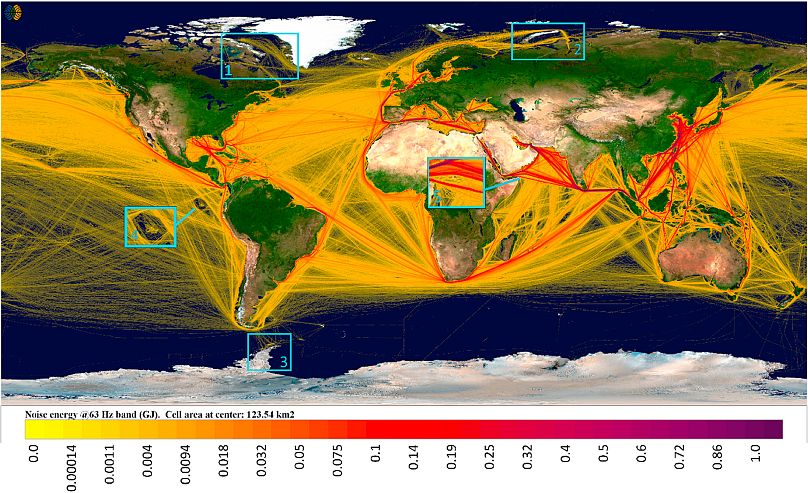

Of these activities, shipping is the biggest noise polluter, currently accounting for about 90 per cent of the global trade. It is estimated that noise along the major shipping routes has increased 32-fold in the last 50 years.

Global map of underwater noise emissions from ships in 2019

This invisible type of pollution is believed to be having devastating effects in some areas, such as the Black Sea.

Between February and August 2022, during the first months of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Turkish Marine Research Foundation TUDAV reported a huge increase in dolphin strandings.

“If you are asking about the whole Black Sea, we had in total over 900 animals stranded. It’s actually more than twice [the amount for] a normal year, and in some areas, more than three times,” explains Dr Ayaka Amaha Ozturk, a lecturer at the Faculty of Aquatic Science at Istanbul University.

Professor Fernández also highlights another highly vulnerable area, one that he calls “a sick sea”.

"Cases of strandings associated with acoustic sources continue to exist, particularly in the Mediterranean Sea," he explains.

“I always say that if I were a fish, a marine mammal, a whale, a beaked whale… I would leave the Mediterranean Sea if I could”.

Seismic surveys - a method used to locate offshore oil and gas reserves - and the construction of offshore wind farms also generate noise that can affect marine animals.

Originally, scientists believed noise pollution was affecting mostly cetaceans, but recent studies show that at least 150 marine species could be suffering the consequences.

But how exactly is noise affecting marine life? And is there a way to solve this issue?

Watch our report above.