The wellness benefits of creating and consuming art are well documented. One historic bathhouse in Istanbul, however, is taking the crossover of creativity and wellbeing to a new level and unexpected directions.

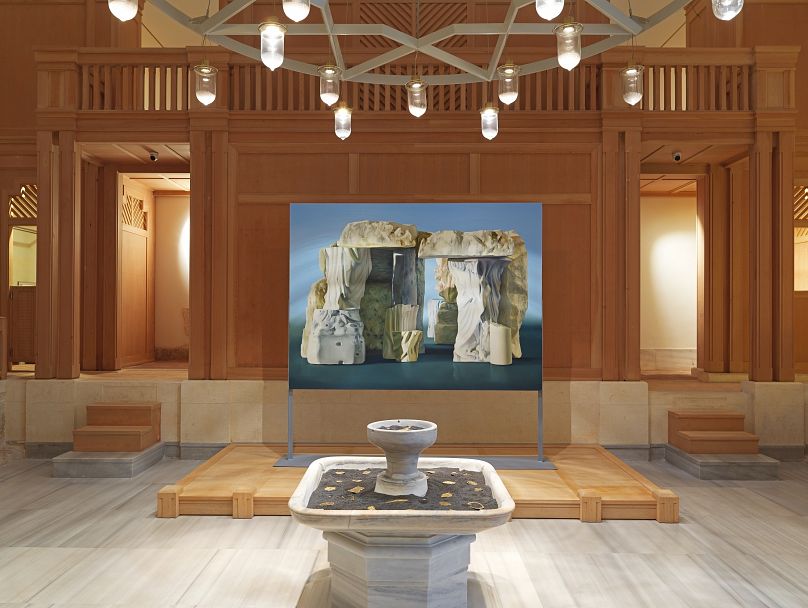

Inviting visitors to take in sculptures, paintings and soundscapes amidst the domes, golden taps and marble fountains of a 16th-century bathhouse, Zeyrek Çinili Hamam is no mere spa, but a catalyst for discussions of history, healing and community.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Nestled in the Zeyrek neighbourhood – a residential and history-rich but relatively poor area on Istanbul’s European side – Zeyrek Çinili Hamam was commissioned by Hayreddin Barbarossa, the Grand Admiral of the Ottoman navy, and built by Ottoman chief architect Mimar Sinan.

Following a painstaking 13-year excavation and restoration process, from March 2024 the Ottoman-era hammam will open once again as a public bath, but this autumn sees a one-off contemporary art exhibition take over the space.

Entitled Healing Ruins, the exhibition draws on the extensive excavation, with artworks (many specially commissioned) taking inspiration from and responding to the layers of history uncovered during the process. Such a title, curator Anlam Arslanoğlu de Coster suggests, resists singular meaning: who is healing whom?

“The exhibition looks into how discovering and restoring layers of history might have a transformative effect on us, both on an individual level and as a society,” she explains. “We can talk about the act of healing ruins: our mental ruins, perhaps, or the architectural ruins of previous civilisations or our history’s intangible ruins.”

Whether literal or figurative, Arslanoğlu de Coster sees great curative value in tending to such decay. “By discovering [the ruins], by confronting them, by having a dialogue with and caring for them, can we actually find ways of healing ourselves?” she posits. Bar the amusement offered by the third possible interpretation, reading ‘ruins’ as a verb – “Preparing this exhibition felt a bit like that for me,” the curator jokes – such a reading points to the often painful journey towards healing.

Healing hands

Among the 22 participating artists are New York–based Iranian multidisciplinary artist Maryam Hoseini, whose work explores ruins within politicised social space; Athens-based sculptor and painter Zoe Paul, who merges conventional craftsmanship with materials derived from industrial waste to explore themes of community and domesticity; and British sculptor Daniel Silver, whose figurative works draw on ancient architecture, archaeology and monuments. They are joined, among others, by Turkish artists Hera Büyüktaşçıyan, Candeğer Furtun and Ayça Telgeren.

Telgeren’s concrete sculptures take inspiration from “healing bowls”, which the artist explains were essential therapies in ancient Asian beliefs. “It was thought that the water drunk from these bowls cured many diseases, especially smallpox,” Telgeren tells Euronews Culture.

Her sculpture Flesh Mirror, which draws most obviously on these bowls, includes an elevation in its centre designed to echo a mountain: “The mountains were the navel of the world, death and life were in union there,” the artist says, with the water poured into the bowl adding a new dimension to the artwork in the form of the viewer’s reflection. “It’s the idea of bringing the past and the present together with my own body and water,” Telgeren says.

Among the most striking works in the show, Candeğer Furtun’s Applause and Legs both pay tribute to and problematise the human form. The artist’s 33 pairs of hands and five pairs of legs are cast in ceramic, disconnected from the bodily whole and thus bereft of their functionality; their lifelessness and repetitive nature at once point to bodily mortality – a fate one might attempt to delay with visits to healing places like hammams – and a rejection of singularity that stands at odds with contemporary conceptions of health and self-care, which are largely focused on the individual.

The themes of plurality and seriality present in Furtun’s sculptures speak to a wider theme of Healing Ruins, and of Zeyrek Çinili Hamam more broadly: community. “The hammam is not just a space for purification or cleaning … for Ottoman society it was an important public space,” Arslanoğlu de Coster explains.

Bringing the past into the present

Rediscovering the Ottoman bathing tradition – which is explored in a museum adjacent to the building, packed with artefacts found during the excavation – is something of an unmasking process, challenging contemporary perceptions of the purpose of the baths.

Creative director Koza Güreli Yazgan draws a contrast between hammams in the Ottoman era and comparable practices in the present day, and hopes placing artworks within the space will help reinstate the baths’ status as a gathering space: “Hammams used to be gathering spaces, they had this sense of community and belonging – they’re not like that any more [...] we’re trying to recreate that sense of community, through arts and culture.”

The contemporary works stand alongside the historical stars of the show, which have undergone their own (quite literal) process of unmasking. Indeed, when Güreli Yazgan first encountered the Zeyrek Çinili Hamam upon her company, the Marmara Group, taking on the restoration, she was puzzled. In Turkish, “çinili” means “tiled” – why did a hammam, seemingly devoid of tiles, bear the name “Zeyrek Tiled Bathhouse”? “When we bought this place we didn’t know [the tiles] existed; it was covered in plaster, it was in decay,” she tells Euronews Culture.

The answer became clear when fragments of elaborate blue and white “iznik” tiles were discovered. Sent during the intervening centuries to museums as far afield as London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, 10,000 of the ceramic tiles – adorned in 37 unique patterns – are thought to have once lined the walls of the baths.

The tiles were not the only treasures revealed during excavation: intricate wall paintings, Byzantine and Roman artefacts dating back to the 5th century, along with a system of Byzantine cisterns, were all uncovered. “The hammam dates back 500 years, but the Byzantine systems and the objects we found take us back through 1500 years of history,” Güreli Yazgan enthuses.

Such discoveries even saw the revising of history presumed known: “The time of the construction was thought to be the 1540s, but through this research process history was rewritten and we now know that the hammam was built between 1530 and 40,” Arslanoğlu de Coster explains.

Today’s Zeyrek Çinili Hamam might be seen as a collaboration or a dialogue, not only between archaeologists and creatives seeking to excavate, understand and restore (or “heal”) the bathhouse, but between this dedicated team and the hammam itself. Revealing its own stories and, in the process, granting an understanding of the lost histories and traditions that shape the present, the hammam holds its own in the healing stakes.

“I think the notion of healing cannot be expected from one side only. Ruins are there as agents for us to understand the notion of time, ruptures of history and how certain cycles operate within the whirlwind of erasure – destruction and re-creation,” participating local artist Hera Büyüktaşcıyan tells Euronews Culture. “Unless we learn how to read what ruins are there to show us about the past as well as today, nothing can be healed.”