Data from Copernicus reveals this has been the warmest winter on record in Europe. What's it like for those who live in the coldest places on the continent? We went to Abisko, Sweden to find out.

Thriving red foxes, rising tree lines and hungry reindeer are some of the effects of climate change we witnessed in Abisko, Sweden, in this special report from inside the Arctic Circle for Climate Now.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Update the record books

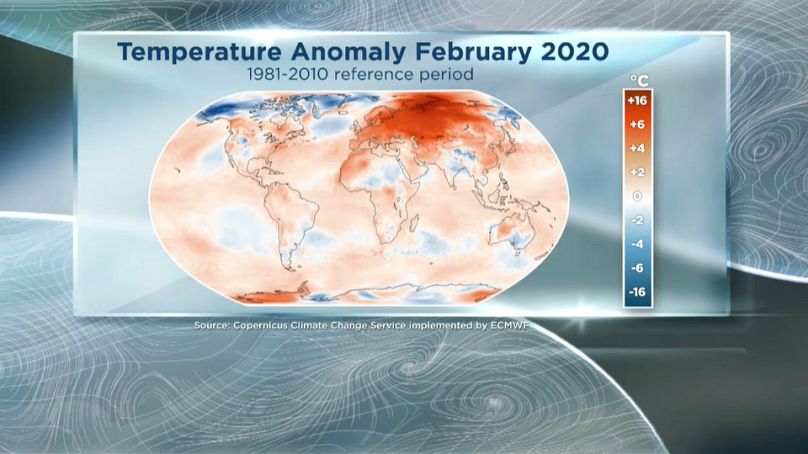

A review of the Copernicus Climate Change Service data for the month of February reveals that it's time to update the record books. Not only was this the second warmest February on record worldwide, but in Europe the entire winter period from the beginning of December until the end of February was 3.4 degrees Celsius above the 1981-2010 average. This makes 2019-2020 by far the warmest winter on record in Europe.

Looking at global air temperature figures for February, late summer in Antarctica was warmer than average, whilst in eastern Australia, temperatures have been lower. Europe's temperatures have also been milder, while those in Siberia and Central Asia have been significantly above average for February.

Arctic sea ice cover was down in February, with research scientists estimating that there are around 850,000 fewer square kilometres of sea ice than expected at this time of year – around the surface area of mainland France and Italy combined.

Warmer in the coldest places

What does this mean for places such as Abisko, in northern Sweden?

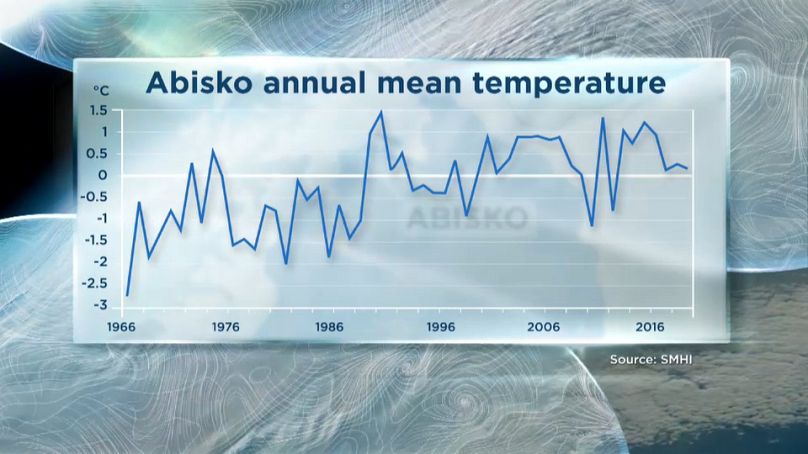

While annual temperatures have fluctuated since 1960, as a result of climate change, the village has seen its average annual temperature rise from below zero to above zero.

On the ground, Abisko still seems extremely cold by the standards of most Europeans. Winter there means snow, ice, and temperatures that average around -15C. But across this frozen landscape there are signs of great change.

"Here we have a weather station where we’ve measured the temperature with a thermometer since 1913. But this tree is a thermometer. And all these trees are thermometers," explains climate scientist Keith Larson, project co-ordinator at the Abisko scientific research station.

Trees and temperature readings from this weather station go back more than a hundred years and show that Abisko is warming at least twice as fast as the rest of the world.

Larson says this is because of feedback loops – as snow and ice melt they reflect less sunlight, making them melt even faster in turn.

"By 1989, with the exception of 2010, all years [have been] warm years. So that doesn’t mean it’s not cold in the winter, this is still the Arctic. But we’ve lost our cold winters," says Larson.

In the tourism centre at the Abisko National Park, an exhibit is dedicated to the changes in the local landscape and what they means for the plants and animals there.

One species made vulnerable by this warming trend is the Arctic fox. "Now, we have the Arctic fox in the higher areas of the mountain. And then we have the red fox coming up. And if they meet, the red fox conquers... the Arctic fox," says Lo Fischer, head of the Abisko National Park Visitor Centre.

In Abisko, locals are seeing changes that they say are not visible to people farther south, such as treelines, which used to be much lower – each year, with temperatures rising, the line of trees moves up the mountain.

For Tomas Kuhmunen, a Sami – an indigenous community that lives mostly in northern Sweden, Norway and Finland – things are getting harder every year for those who still live traditionally, herding reindeer.

Warmer weather means more rain, which turns to ice, locking lichen into ground and leaving reindeer to starve. Kuhmunen says some families this year have corralled their reindeer and are feeding them by hand, even though they say It’s not good for the animals.

For him, the future is uncertain. "When we ask our elders, [what] do you do when the winters are like this? [What] did you do? And our elders [say], we don’t know."

But it isn't today that Kuhmunen worries about, it’s how winter will be for the next generation – or whether winter as he knew it will come back at all.