Via site-specific commissions, sound and video installations, sculptures, films and 3D-printed objects, Weather Engines explores themes, locations and historical contexts.

“What’s up with the weather?” As we ask this perennial question, we're actually engaging with questions of politics, technology and justice – at least, that’s the idea put forward in Weather Engines, a new Athens exhibition launching on 1 April.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) latest report, global warming is causing (in some cases irreversible) changes to rainfall patterns, oceans and winds in all regions of the world.

Europe can expect an increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events. Weather Engines takes this climate crisis – and the data surrounding it – as a catalyst for reflection on what curators Daphne Dragona and Jussi Parikka call “the poetics, politics, and technologies of the environment from the ground to the sky, and from soil to atmosphere”.

Via site-specific commissions, sound and video installations, sculptures, films and 3D-printed objects, together with a public programme of talks, performances, and workshops, Weather Engines explores themes, locations and historical contexts as diverse as the Aztecs, 1970s Canada, the Colombian Amazon and an Alpine glacier.

“Oceans, clouds, and forests are acknowledged as life-sustaining engines, creating the atmosphere that we are inhabiting but also affecting,” say Dragona and Parikka of the exhibition, which is taking place at the Onassis Stegi and the National Observatory of Athens.

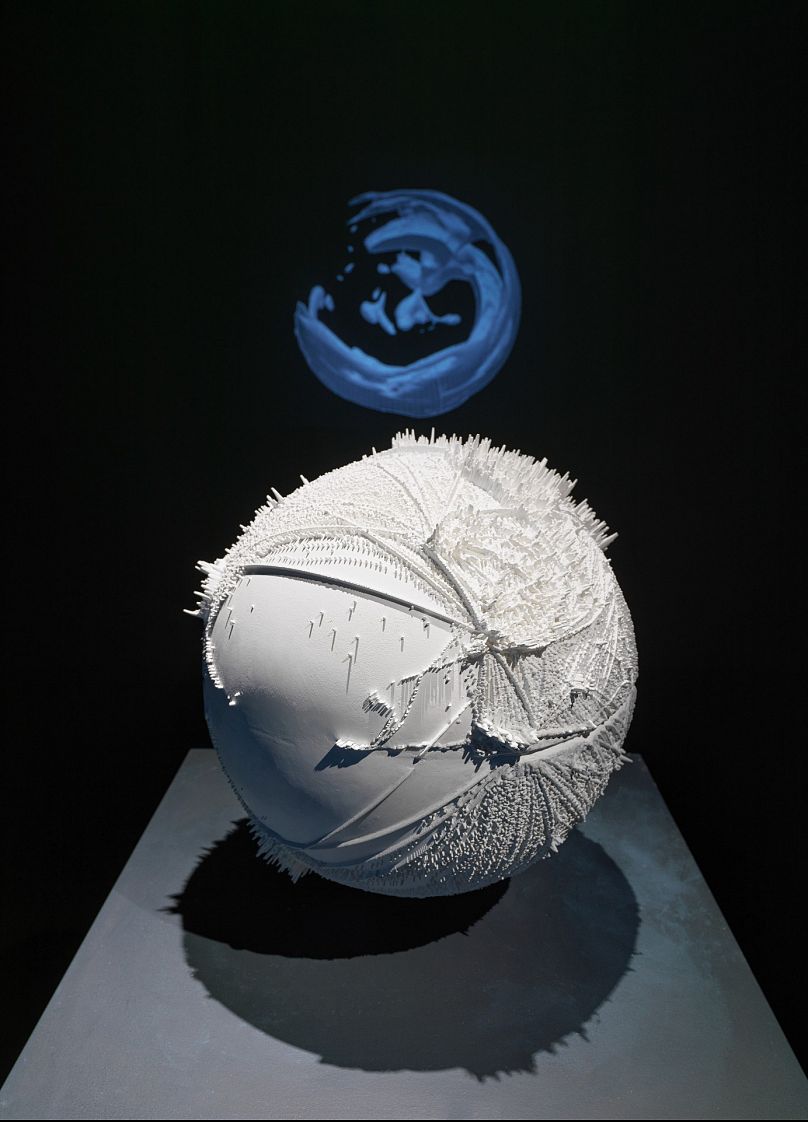

In her installation “Bodies X-XV”, for example, Cypriot artist Lito Kattou’s anthropomorphic figures – with elements of fire traced on their bodies – evoke the warming climate of the Mediterranean and its human causes.

“In the devastating summer of 2021 we all witnessed here in Athens and in Cyprus, my birthplace, the most violent and destructive wildfires ever to take place,” Kattou explains. As the only one of the four classical elements that humans can produce themselves, fire “bridges the connection between mortals, the gods, nature, technological and industrial development”. Though these have “brought the advancement of human civilisation”, they are “responsible for the deterioration of our environment's conditions”, Kattou reflects.

Beyond unthinking environmental damage, other projects expose the exploitation and weaponisation of weather, challenging viewers to interrogate the neutral character of these (un)natural phenomena. In her video project “Cold Cases”, UK-based artist-researcher and writer Susan Schuppli evokes a new “thermo-politics”, in which “temperature becomes a register of violence”.

This violence, she explains, is a manifestation of structural racism and climate colonialism, and exemplified by the Euro-centrism of climate bodies: “The discussion in the IPCC about accepting a two-degree global rise in temperature [...] is a political choice as much as a scientific proposal, given that two degrees is manageable for Europe but would be a death sentence for some other countries, especially in Africa,” Schuppli explains.

While “most people tend to think about warming, not cold, when they invoke thermo-politics”, she comments, the new thermo-politics weaponises cold. The first film within “Cold Cases” entitled “Freezing Deaths & Abandonment Across Canada”, for example, details a racist practice referred to as a “starlight tour” – a practice in Canadian policing that involves driving Indigenous people taken into custody to isolated areas and leaving them in frigid conditions. “The use of cold as a clandestine tactic in Canadian policing was a direct consequence of settler-colonialism and racism [...] the weather (something seemingly beyond the control of the police) has been used as an instrument of punishment,” says Schuppli.

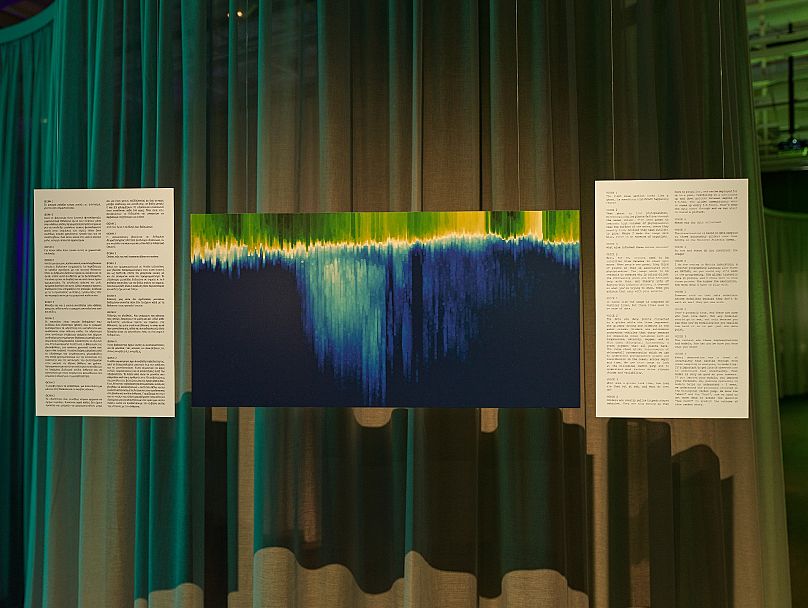

It is not only the weather itself that can be exploited, but its study and encapsulation in data. Collection and presentation of data are the jumping off points for Matterlurgy, whose work elucidates and problematises the collection and presentation of climate data.

“Through our work, we are interested in developing a critical perspective on technologies of data collection, examining the modes and methods through which environmental data is constructed, made visual and operational,” explain Matterlurgy, a collaboration between London-based artists Helena Hunter and Mark Peter Wright.

“Data can be used as propaganda or weaponised, as with any science or technology. It can also be gathered and deployed for environmental advocacy, so it’s not an either-or situation,” say the artists.

In their film installation for Wind Engines, Matterlurgy focus on ocean sensing, and shed light on the processes and technologies involved. The first film, the psychedelic “Hydromancy”, brings together documentary footage shot at the UK’s National Oceanography Centre (NOCS) with artist interventions, against the soundtrack of the Hydromancer.

This atmospheric voice poses questions that capture the frustration (and sometimes futility) of scientific enquiry: “What more can I say? What more can I know?”. “Hydromancy is an ancient practice of divination by water. It’s an alternative method that queries scientific language, representation and forms of knowing,’ say Matterlurgy.

The second film, “Data Dialogues”, overlays a conversation between the artists and NOCS scientist Dr Filipa Carvalho on the process of data visualisation with images collected by an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle, processed by Dr Carvalho. In casting it as both an object of scientific study and a sensory environment, the project calls into question the ways in which we attempt to know, understand and present the ocean. “Like a sensory anthropology of the sciences, our work focuses on the spaces, people and technologies involved in producing data.”

Transdisciplinary research group Manifest Data Lab, based at London’s Central Saint Martins, engage with these questions to propose alternative methods of data representation. Their “Carbon Topologies” project visualises data that is normally invisible, mapping the locations, amounts, and flows of CO2 resulting from the global economy from the 1970s to the present. The process of mapping this data across a planetary model reveals inequalities, linking emissions to wider political processes of inequality and power distribution usually not captured in more traditional data presentation. “Climate is multidimensional, encompassing interactions across huge temporal and planetary scale systems, so it is inherently abstract – even if its results are catastrophically present,” says Tom Corby of Manifest Data Lab. “Our approach is to take this intangible data and make it temporal, present and physical with the intention of developing visceral and emotional shortcuts that enable intuitive and critical (sensed) understandings of it.”

The work of Greek artist Zissis Kotionis chimes with this sentiment. The question he poses, however, is perhaps more radical: when it comes to the weather, is quantitative data helpful at all? His project “Barometer and Aerographs” proposes structures that measure weather and time (“kairos”, an ancient Greek word meaning 'the right, critical, or opportune moment and also “weather” in modern Greek) with non-measurable indicators – a contradiction that aims to highlight the weather’s limited measurability and the reductive nature of its representation in quantitative data.

Kotionis’s “Aerographs”, for example, are wind-meters that record the sensory impact of the wind; reeds, hanging from the branches of a tree moving with the wind, gently carve into sand placed below. “Can we reach an experiential involvement in the physical aspects of the weather through our sense of things, instead of an approach through information and data?” Kotionis asks, with his work seeking to disrupt what he calls the “neurotic treatment of meteorological data by the media”, in which increased data renders the weather evermore inanimate and unknown.

Human beings, we might understand from Wind Engines, have a lot to answer for when it comes to weather and its weaponisation. With alternative models of understanding centred on making data tangible and allowing it to be “experienced” – to allow viewers to have “felt those energies, the noise and frequencies that underpin a smooth or silent chart or spectrogram,” as Matterlurgy posit – human subjectivities and sensibilities may be at the heart of a journey towards healing and climate justice.

This capability is brought to the fore in Kattou’s work, where fire is both a symbol of destruction and hope: “The element of fire traced on the bodies implies [they] have departed from turbulent locations [...] capable of healing traumatised places,” says the artist.

Indeed, the power of humans to impact the climate is both terrifying and optimism-inducing. After all, as the curators suggest, “In the age of anthropogenic climate, all weather is artificial. If all weather is made, then this also means that there is still the potential to struggle for the weathers and climates we would rather live in.”

Weather Engines is an Onassis production and runs until 15 May 2022.