The study findings could open up new possibilities to monitor brain inflammation simply by scanning the surface of the patient’s head.

Monitoring and treating brain conditions such as Alzheimer's and strokes has been a challenge due to the vital organ’s inaccessibility.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The brain is protected by the skull and other surrounding membranes.

Now scientists at Helmholtz Munich in Germany have uncovered a more complex relationship between the skull and the brain.

They say their findings could offer new diagnosis and treatment options and“revolutionise brain health monitoring in the future with non-invasive skull imaging”.

Immune cells trying to access the brain

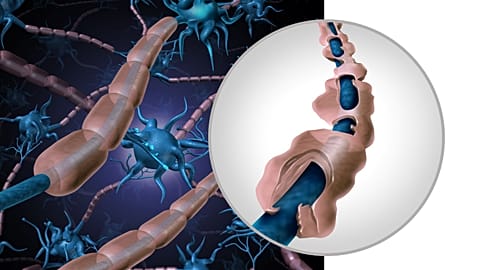

Recent studies have suggested direct connections between the skull's bone marrow and the outermost surface of the brain's protective membranes, the meningeal surface.

“The team of scientists found that these connections often traverse even through the outermost and toughest layer of membrane, the dura, opening up even closer to the brain surface than previous thought,” according to a statement from Helmholz Munich.

Neuroinflammation, a common feature of neurological diseases such as Alzheimer's, stroke, and multiple sclerosis (MS), can be caused when immune cells from the skull get into the brain.

“To give an analogy, you can think of it as a castle. The brain is inside and there's the army outside. They [invaders, the immune cells] want to destroy the inside, but they're blocked, right?” said Ali Ertürk, head of the Institute for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine at Helmholtz Munich.

“But there are actually small gates we found with this study, with high-resolution, there are tiny, small gates - that people didn't know (of) before - in the wall. And these gates can open and when they open, these guys get in, and then they cause brain damage," he added.

The researchers also found using PET imaging that signals from the skull mirrored those from the underlying brain. The changes in these signals corresponded to disease progression in patients with Alzheimer's and stroke.

Tissue clearing and 3D imaging

The team also found, in analyses of both mouse and human bones, that the cells in the skull’s bone marrow are “unique in their composition and in their disease response” and those "brain-specific" cells and molecules harboured in the skull cannot be found in other bones.

To generate high-resolution images of the skull, meninges, and the brain for the first time the research team used “tissue clearing”, a specialised method to make organs and bones transparent.

"Think about this like looking into a glass of milk versus water. What we do is converting milk into water, and that requires some biochemical processes, including dehydration. And we remove the white particles of the milk. Then the transparent part remains. When it's transparent like this, light can travel, and then we can visualise inner structures,” Ertürk explained.

The team then used 3D imaging to visualise the conduits facilitating the movement of immune cells back and forth.

"We could see them cell by cell, end to end. And that revealed to us that indeed there are also connections between the human skull and the surface of the brain, and we are now able to utilise these connections, first to monitor brain diseases and potentially to treat brain diseases,” said Ertürk.

All these findings together open up new possibilities to monitor brain inflammation simply by scanning the surface of the patient’s head using ultrasound or other methods. It could also enable early diagnosis and "potentially even aid in preventing the onsets" of the diseases.

Ertürk's team of about thirty researchers who worked on the project for over four years hopes that “more accessible and practical ways” to monitor neurological diseases will be developed.

For example, small, portable detectors could be attached to the head permanently to deliver a continuous stream of information instead of periodic MRI and PET scans.

“Our vision is that as the skull is just the surface, we don't need to put people into MRI machines, but potentially using smartwatches or as small detectors. We just put it to the surface of the skull and that will show you what is the disease in the brain,” said Ertürk.

For more on this story, watch the video in the media player above.