Climate change leads to heatwaves in the sea as well as on land. We investigate the long-term effects of marine heatwaves in the Mediterranean, and ask if anything can be done to help iconic colonies of corals to survive.

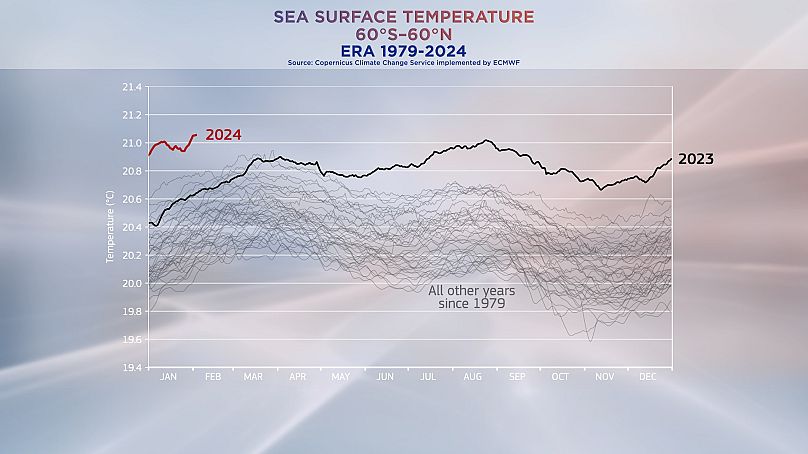

The latest data on sea surface temperature has made a big splash in the news, as the Copernicus Climate Change Service reported that the figures have reached new, record highs already this January. So what impact are these rising sea temperatures having on marine life below the waves? We explore this question in this episode of Climate Now.

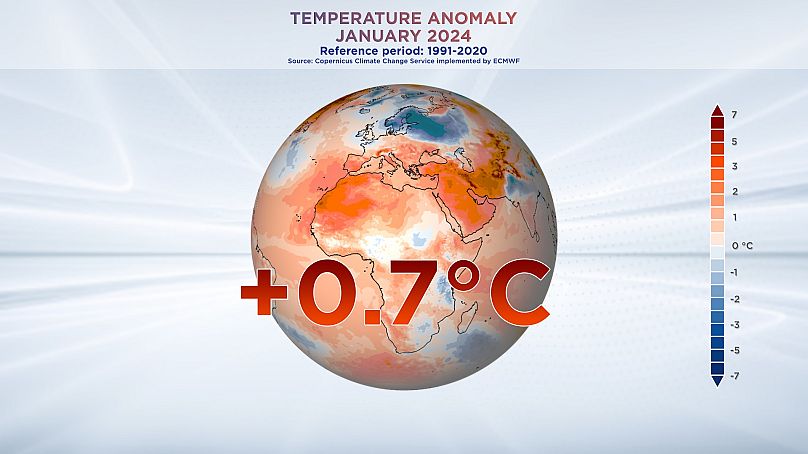

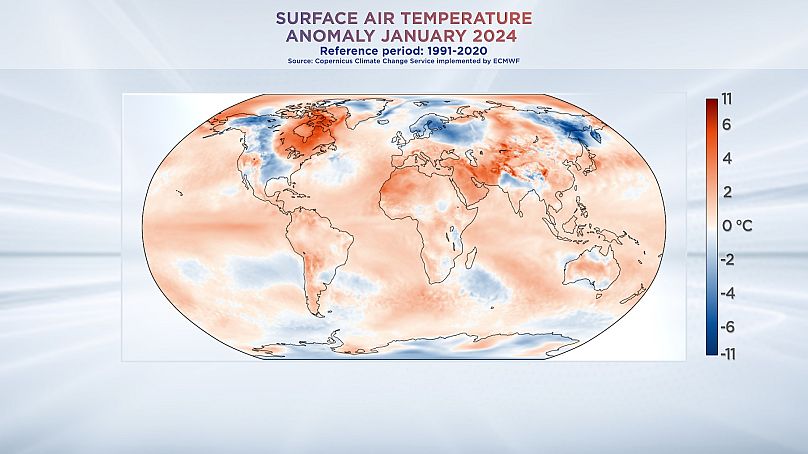

Before we get into this, a quick reminder of the latest Copernicus data, which reveals that we had the warmest January on record, with global temperatures 0.7 degrees Celsius above the 1991-2020 average. We have also experienced the warmest 12 months in succession on record, with an average temperature over 1.5 Celsius above the pre-industrial level for the first time. This symbolic threshold is a key target of the UN's Paris climate agreement.

There was considerable variability in Europe's weather in January, however. Parts of Scandinavia experienced their coldest temperatures in decades, while in Spain there were highs at the end of the month over 8 degrees above average.

In the oceans between 60 degrees north and 60 degrees south - the seas between the two polar zones - the average sea surface temperature worldwide averaged 20.97 degrees Celsius. This is a surprising figure on a par with the absolute highest ever average of 20.98 degrees Celsius, recorded in August 2023.

Such sea surface temperatures do not augur well for the summer of 2024, raising questions about how resilient certain important ecosystems like corals can be in the face of repeated pressure from periods of warmer water.

Heading out to Les Pharillons

With that in mind, the Climate Now team set off for Marseille to go diving with the researchers from NGO Septentrion Environnement. When we joined them, they were putting their gear on and heading out to sea.

"Today, we're going to carry out a census of the health of the populations of red gorgonians at a depth between 30 and 40 metres at a site near Marseille called Les Pharillons," explained marine biologist Tristan Estaque.

He stressed the need for frequent visits: "The aim is to carry out pretty regular monitoring to see how the health of these populations deteriorates gradually over time."

The picturesque coastline of the Calanques National Park was hit by marine heatwave conditions in 1999, 2003, 2015, 2022 and 2023.

It now means that colonies of corals and gorgonians have disappeared from the first 10 to 20 metres of water. In deeper, cooler water, these special species are still thriving.

"The fact is that everything that was dead in 2022 is still dead. There are still a lot of skeletons of gorgonians," says Tristan, indicating that recruitment of new corals has not happened since the persistently high temperatures of recent years.

"When you get to around 35-40 metres, you start to see a dense population, in good health, like it was in previous years. So they haven't been hit yet."

Taking images to document change

The video and photos the scientists take offer them a solid base to monitor how marine heatwaves are killing off certain species in the Mediterranean.

Justine Richaume shows us three photos of the exact same area near Corsica to illustrate what's happening. In the oldest photo, dating from 2015, "You can see colonies of Mediterranean red coral in perfect health. In the second image from 2017 we can see that the colonies are starting to die. You can see necrosis and dead tissue. This could be due to waves of thermal anomalies."

"And finally, in the last image, from 2023, we can see that these colonies of red coral have completely fallen away, showing a rather flat structure to the habitat, and there's no habitat available for the fish."

Globally, the number of marine heatwave events has doubled since 1982, and species that can't move, like corals, are some of the worst affected.

What can be done to help the corals?

Scientists say the main thing we can do to help them is to prevent fishing and tourism around vulnerable areas. Anchors, flippers, pollution and certain fishing techniques can leave corals damaged and unable to recover.

"Perhaps by removing human pressures, we would give them a chance to adapt. Perhaps a mutation will emerge and we'll have super-colonies that are adapted to climate change and that will then, in a perfect world, be able to reproduce and reconquer the layers towards the surface," explains Tristan Estaque.

However, Justine Richaume sounds a note of caution that any recovery could take shape soon.

In the Mediterranean at least, she says, "On the scale of a human lifetime, we won't be able to go back to the landscapes that were lost, for example, following the marine heatwaves of 1999, 2003 and 2022."

Marine heatwaves are forecast to become more frequent and intense as the planet warms, and even in the best conditions, these species grow at just a few millimetres per year.

The team from Septentrion Environnement will continue their mission of surveying the corals, documenting decline, and educating local people and decision-makers about the importance of these ecosystems for biodiversity in the Mediterranean. With invasive species, pollution and high water temperatures posing an increasing threat to these waters, it's vital to raise awareness and install protective zones to give the corals a chance to survive.

Thanks to the Copernicus Climate Change Service, Septentrion Environnement, Associated Press, Office de Tourisme de Marseille, Marineheatwaves.org, and the Calanques National Park.