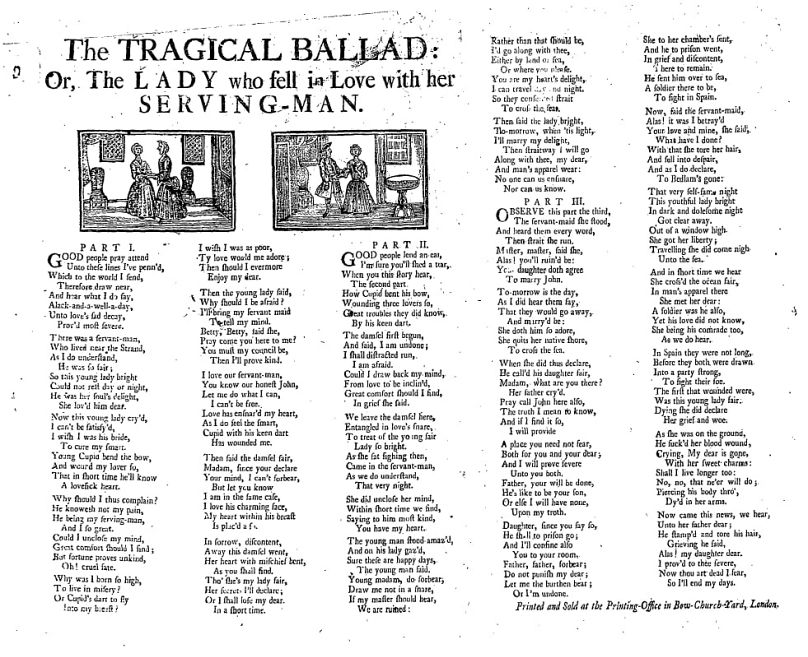

The sale and distribution of popular songs was completely different in the 17th century but there are still some elements which remain within today's music industry right across the continent...

Ballads were all the rage, and we’re not talking about 'Stairway to Heaven'.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

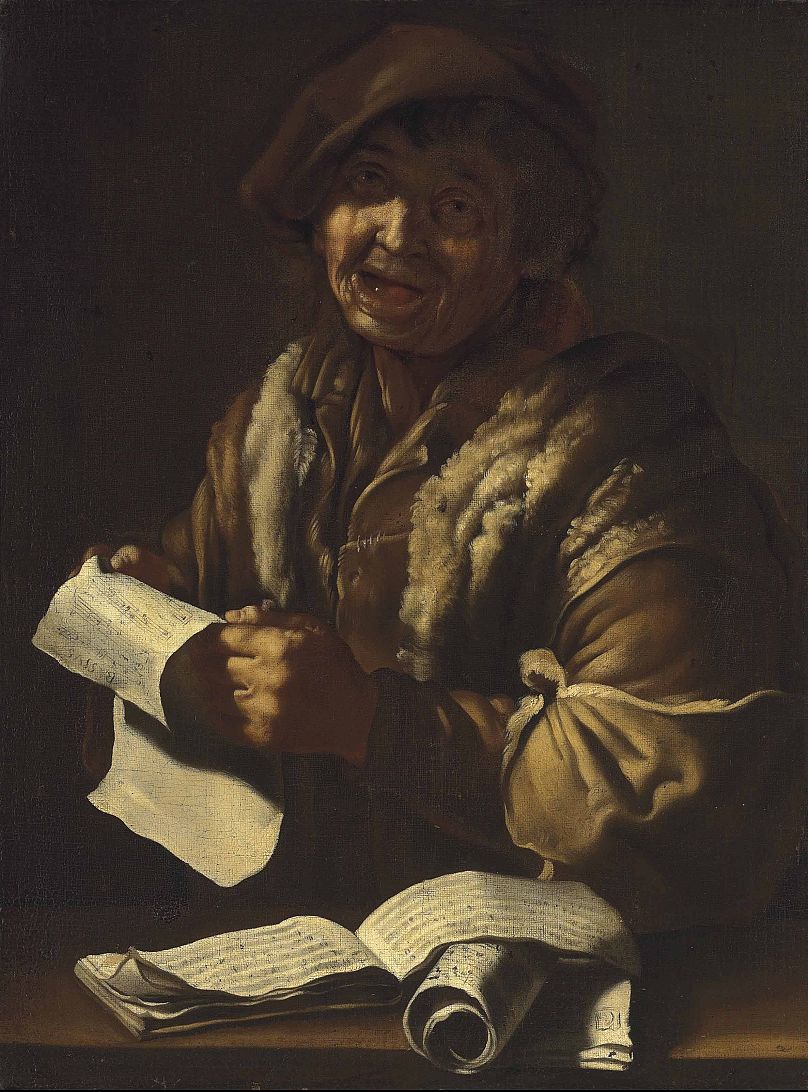

These were songs sung straight from the mouths of balladeers: musicians who went from place to place setting lyrics to music for the public’s listening pleasure.

The tunes they played were often already well-known. But instead of coming up with the lyrics themselves, these itinerant performers might have just bought a new sheet of lyrics from a budding songwriter.

And so the commercial music market as we know it was born.

This is according to a new UK study called 100 Ballads, the work of Christopher Marsh, a history professor at Queen’s University Belfast, and Angela McShane, an honorary reader at the University of Warwick.

As part of the project, Marsh and McShane identified some of the 17th century’s top listens, then invited contemporary musicians The Carnival Band to recreate them so that anyone interested could enjoy them for free on the project’s website.

And while this might all sound very quaint, dating as it does from the time of Shakespeare, when it comes to the music market time doesn’t heal all.

Songwriters during this period could expect their work to fetch a standard fee of one penny per sheet, which remained constant over the course of a century in spite of inflation.

One look at Spotify’s current royalty model might suggest that these are still the going rates.

What about Europe?

Interested in what the 17th century music scene was like beyond England's borders, Euronews Culture contacted the project’s Christopher Marsh to learn about what was going on across the channel.

Though the purview of the 100 Ballads project is English, Marsh told us that "there is now lots of work going on that is demonstrating very similar patterns of publication, sale and itinerant performance in France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway and what is now the Czech Republic.

Unfortunately, the picture we’ll be able to form of the music scene in these places might end up being less complete than in England, simply because ‘the survival rate … is higher for English songs than for those printed elsewhere."

This is because ballad sheets were an inexpensive form of publishing, and in contrast with Europe, ‘the most distinctive thing about English ballads was that many of them were collected and preserved for posterity.’

Compare and contrast

Despite this, Marsh tells us there is still lots of overlap between the music English and other European markets were listening to at the time.

Often the tunes themselves would carry across the channel even if the lyrics didn’t. One tune, ‘Fortune my Foe’, which Marsh says was ‘probably the best known ballad melody in 17th century England,’ definitely made the journey.

Marsh says it was ‘used for the singing of literally hundreds of songs in the Netherlands, where it was known as 'Englesche Fortuyn' and 'Fortuyn Anglois'.

If you want to hear it for yourself, hop across to the 100 Ballads site and queue up ballad No. 20: “A sweet Sonnet, wherein the Lover exclaimeth against/ Fortune for the loss of his Ladies favour”.

And just as the English market exported its tunes to the continent, so too the continent sent its melodies to England. According to Marsh, ‘the tune known in England as “Rogero” derived from a piece of music known in Italy as the “Ruggiero” air.’

Likewise, what the English would have called the 'Spanish Pavan' "had its origins in Italy, after which it travelled first to Spain and then to England’.

To give those a listen you’ll want ballads No. 10 and 99 respectively.

European news was set to music

To Marsh "it's clear that lots of European stories were picked up by English authors and turned into highly successful songs."

Sometimes these stories were based on real events, sometimes not.

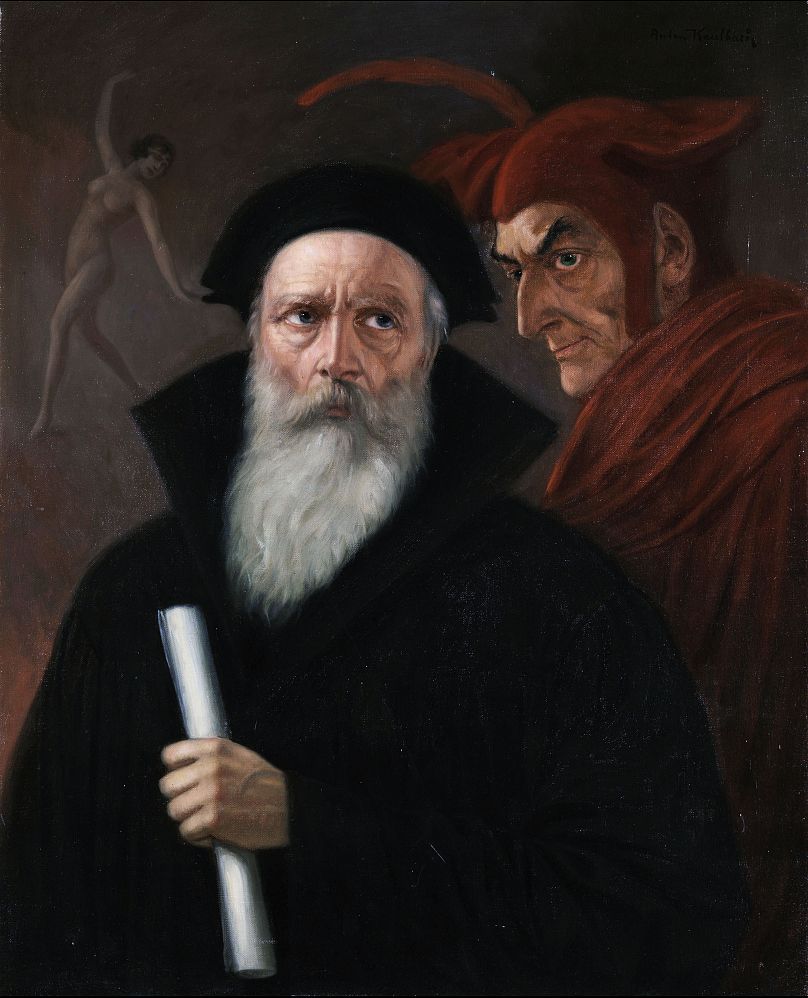

Ballad No. 35 is about Faust’s pact with the devil, which Marsh says was probably inspired by a German pamphlet of 1587.

He credits ballad No. 29, about a black servant who kills his white employers, to ‘the 'novelles' of the Italian Friar, Matteo Bandello, published in 1554.’

In terms of what Marsh calls the ‘supposedly “true” stories about English travellers on the continent’, ballads no. 6, 22, and 31 all give outlandish accounts of Englishmen journeying through Europe.

But it wasn’t just plagiarism and tall tales.

Marsh points out that "it is clear from the content and popularity of the 100-plus super-successful songs on the website that English ballad consumers were deeply interested in stories and news from the continent."

He cites two examples from many: "No. 56 celebrates the lifting of the Ottoman siege of Vienna in 1683; and No. 74 includes a song about a French maiden who was executed for her Protestantism in the mid-16th century."

Perhaps there’s not too much for a modern audience to relate to in those. But as for ballad No. 31 referenced above, that one still lands.

Marsh says it’s about ‘two English travellers who toured Europe between the 1660s and the 1680s’. Their trip is rather spoilt by being ‘scorned everywhere because the English had executed their king in 1649.’

While the lyrics might change, and the music with them, the continent’s antipathy towards English tourists and their political decision-making will always be a hit.