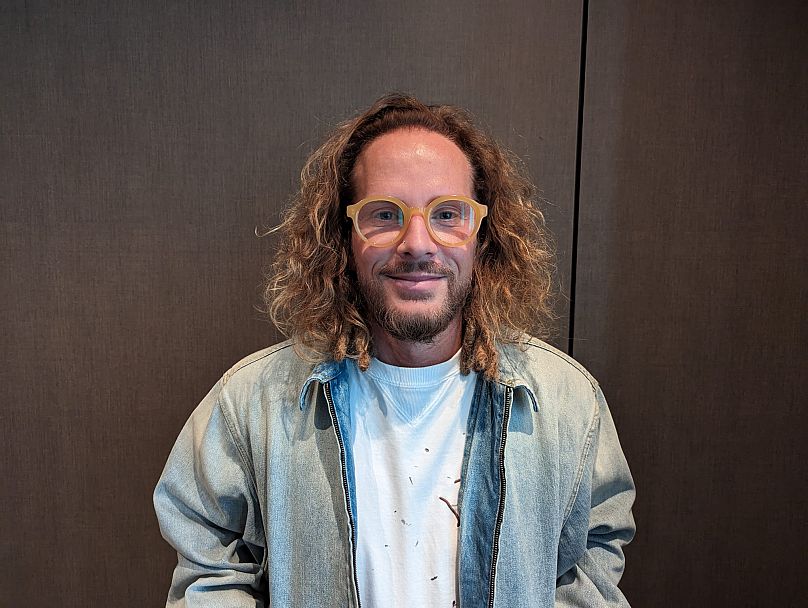

Rare are films like 'The Strangers' Case' that manage to combine striking authenticity with suspenseful, pulse-racing thrills. Euronews Culture sits down with veteran producer, director and activist Brandt Andersen to discuss his film, starring Omar Sy and premiering at the Berlinale.

After his Oscar-shortlisted short Refugee, US producer and activist Brandt Andersen makes his feature directorial debut with The Strangers’ Case, a kaleidoscopic portrait of the refugee crisis that world premieres in the Berlinale Special section.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The Strangers’ Case follows a chain reaction that involves five different families in four different countries. The tragic spark that ignites a chain of events is an explosion that forever alters the lives of a Syrian family in Aleppo. From then on, the film chronicles interweaving perspectives of a doctor, a soldier, a people smuggler, a poet and a coast guard.

The film boasts an international cast that includes French star Omar Sy (Father and Soldier, Lupin), Yasmine Al Massri (Quantico), Yahya Mahayni (The Man Who Sold His Skin) and Ziad Bakri (The Weekend Away), and the end result is a breathtaking achievement that packs a visceral punch.

Rare are films that manage to combine striking authenticity with suspenseful, pulse-racing thrills, and The Strangers’ Case never compromises the integrity or scope of humanitarian crises by putting the accent on compassion at every turn. It’s a tricky balancing act to manage, but Andersen achieves it by directing with piercing precision and injecting a wealth of experience into a film that features several scenes that imprint themselves onto your psyche.

Raised by American missionaries, Andersen has worked with humanitarian agencies, documenting the living conditions in refugee camps in Turkey, Greece and Italy. In 2019, he visited and filmed in hospitals outside Aleppo in Syria, as well as organised film camps for refugees in Jordan and Turkey. This insight provides The Strangers’ Case with a simple yet hard-hitting thesis: by exposing the connective thread that binds lives together, no matter how far-off events may seem to be, they can impact countless lives in unseen and unexpected ways.

Euronews Culture had the pleasure of sitting down with Andersen to discuss his film.

Euronews Culture: The Strangers’ Case starts with this Shakespeare quote, a defence of refugees. Can you elaborate about the choice of this particular quote?

Brandt Andersen: This particular quote from Shakespeare is the only thing that remains in the hand of Shakespeare. It exists in the British Museum and it's the only thing we have in his hand that he's actually written.

It was a conglomeration of writers at the time who came together to make this play for Sir Thomas Moore, and the reason I felt it was so powerful was because it shows that we're dealing with the same things today that they were dealing with 400, 500 years ago. It’s a cycle that has not ended, and it's not any different. To me, the film is also quite Shakespearean in the way that it unfolds.

The film takes this kaleidoscopic approach to humanitarian crises, almost like a butterfly effect. Why did you choose this particular narrative structure to tell this story – or should that be, these stories?

That’s a great way saying it, by the way – a butterfly effect. Can I go off base for one second?

Please do.

I have some artists friends, and this artist, who’s quite well known... One night, he came over and he was... He was very out of sorts, let's say. And at some point, he put a knife to my neck.

As you do...

I remain calm, but then as soon as he finally moved the knife away from my neck, I asked him to immediately leave. His manager called me the next day and told me that the artist wanted to bring me one of his pieces. I didn’t really want them to come back, but the manager told me that he insisted – “What do you want it to be?” I said “Well, why don't you have him do a piece of art for me that represents the butterfly effect.” And so this hangs in my house. And this idea that some action somewhere very far away, albeit small, can have a huge effect somewhere else in the world, and that it can increase in what that means... That is a principle that I really believe in. I see that in my life, everywhere I go.

If you're kind to someone in some part of the world, you may find that months or years later, you'll meet someone else who knows them in a whole other part of the world, and they've referred to that kindness that you did over there. These connecting threads that run between us are so strong but yet so sensitive. In making this movie and the structure of it, it makes sense because I feel this deeply. I believe that people love each other, and they want to be with each other, and there's so much more that's similar about us than different.

One thing that struck me about the film is that some sequences outshine most thrillers out there in terms of tension. Was it difficult for you to broaden the scope of the topic without diluting its authenticity by not only looking at these different characters but also utilizing the cinematic language of the thriller genre, for example?

I have kids and I see how they are consuming media these days. It’s mostly YouTube and the social media type of consumption. So, I felt that on a topic like this, which I really want to receive wide appeal, I needed to create an environment that would be approachable for people in the way that they're consuming media today. I think of it as a drama with thriller elements to it that keep you in it. I want this film to reach people on a level that they're comfortable with, and then allow them to take the emotion that's on the screen and put that into their own life. That's my hope. David, do you have kids?

I don't.

Do you have nieces and nephews?

I have a young nephew.

At any moment, did you see your nephew in the kids on screen?

I did, yes. Especially during the boat scenes, it was impossible for me not to project myself and fear that someone I love like my nephew would face the possibility of drowning.

And that's the thing. When you think about that, you can't help but go “I've got to make some changes.” And that's not just for you - that's me too. If I’m moved by something, I’ve got to go all-in more. Whether you have a brother, a sister, a nephew, or just a neighbour kid that you feel deeply about, if I can help put you in a position where you can allow yourself to be vulnerable, then cinema’s doing its job.

From my standpoint, when I was a kid, I was moved by cinema and it made change for me in my life, and it taught me things not because that's what I think the filmmaker was always trying to do, but because it gave me a very safe space to do that. And this is a safe space. I'm not telling you what to do. I'm not telling you how to feel. I'm just saying- here is this experience. This is a true, authentic experience of what these people are going through. And as human beings, we can’t just sit by. It's one of the reasons why I believe the kids are so important in this film. We have to make some changes, and I want people to see the film because I want them to be able to help.

I recently interviewed Agnieszka Holland for her film Green Border, which also deals with a devastating humanitarian crisis, and she told me how we need important films right now. We need courageous films, but it’s harder to find funding for films which are politically engaged. She also told me that no one film can change the nature of global politics, but that hopefully a film can help to raise awareness...

I disagree with her on that. I do think that one film can change that. It may not change the whole world of it, but I believe deeply that we should not defund UNRWA (United Nations Relief and Works Agency) right now. I’ve been to Gaza, I know what's going on in Palestine, and UNRWA needs to be there right now. And if let's just say, totally separate issue from what's in this film, but if I can use this film to help influence those people who make those decisions to say “We need to be more compassionate”, then that's a direct change in policy from one film.

So, I think we need a lot of these films to change the overall climate of emotions from people. But the people are the strongest arm that we have, and if we can say “We want we want to see more compassion, we want to see more change”, then the people can demand change from the leaders. These extremist leaders that we have, who are speaking the loudest... It's hard to watch because compassion gets no play from leadership right now, and I do believe compassion is still very much alive. So, I hear what Agnieszka Holland is saying. I'm grateful for all films like lo Capitano and Green Border – those films are important, and they're beautiful. And I love that filmmakers are making those films. She's right - they're very hard to make financially. But social change is possible, even through one film.

Your directorial debut was Refugee, and you’ve worked with humanitarian agencies and have observed what goes on in refugee camps in Turkey and Greece. Would you say that cinema is an extension of that humanitarian work?

Yes, absolutely. I didn't intend it. It didn't start out that way, but it's an extension. It's like a by-product of it. I will continue to do humanitarian work, no matter what happens, with my film career after this. Because it enriches my life, and I believe I can help create solutions to some of these problems. I don't always know what those are, but I have to work off the fact that I can believe that I can do that, or it would be too daunting to even go into it.

I know I can tell stories. I met with a smuggler to understand how and why they're smuggling, and what the thought process behind this is. I was with refugees who are getting on the water or on the other side helping them get off the water... I’m trying to find ways to help. And what comes out of that is I tell their stories. This is what comes out of me, and there is no set plan. This is just what my heart tells me to do, and I have to follow that to be true. As corny as that may sound.

The Strangers’ Case premieres at the Berlinale this year, and Berlin Film Festival has a reputation for being politically active. Do you see film festivals as contributing in a meaningful way to these vital socio-political topics? Because the second there are cameras and red carpets, activism can feel a little performative and photo-opy...

I give the Berlinale and Carlo (Chatrian, artistic director) huge props for being willing to show the film here. Not everybody would. I think that's bold. You've got a festival that's funded by the government here, and I know they have their limitations. But, the festival wouldn't happen without it being funded by the government. You can't upset everyone and have everyone show up, you know? I think I understand how those things work, maybe more than somebody who just says “Fuck this situation and I'm not coming.” I understand why they feel the way they feel, and they're entitled to that. I think people are entitled to their voices in this situation. But I think Berlin has done a better job than many at walking this line. Are they perfect on it? No. But they acknowledge what the issues are, and then they try to do what's right. You can't make everyone happy.

And in a case like this, on a film on Syrian refugees, made by someone who primarily speaks English, you need someone who's willing to say “Okay, I believe in this film, and we’re going to show it here at the festival”. And respect to them for doing that.

With the regards to the casting, one major name is Omar Sy, who delivers a performance that far from a lot of the roles he usually plays. His character of a people smuggler is detestable, but you also see him with his child, and have sympathy for him as a father. How did your collaboration come about?

Well, the script got sent to his agent and then to him. He said he’d love to meet. He was shooting in France, and at the time, I was on a non-profit visit to Lampedusa, seeing what was happening with refugees who were coming from Libya. I said I would go back through Paris and have dinner with him. And we just hit it off. We just had this very good, shared energy - our kids were the same age and our real desire to better what's taking place with humanity. We really bonded over that and became very close. And so he was the first one to sign on for the film. He was a great collaborator throughout, and he's one of my closest friends.

Without spoiling too much for readers, but the ending of the film feels like a plea to take notice of the multi-facetted nature of people, and not stay stuck in preconceptions. And I don’t know whether this is me reading too much into it, considering the final scene takes place in the US, but it felt like a subtle dig at American exceptionalism, at a country where the term “globalist” is an insult. Was that the case?

We’re living in a very nationalist moment unfortunately in the United States – and really all these countries. Nationalist populism has become a very important issue to people. I don't feel that way, personally. Maybe that's because I've grown up in different places. I don't feel this sense of nationalism. I love the country that I was born and raised in, but I welcome diversity. I thrive on diversity. I need that to feel like I'm squeezing all the juice out of life, you know?

So, it wasn't so much like a dig at the United States - although there's plenty of digs I could take. But it is what you said about taking a second to look at the things that you think you know so well. We bring all this bias from our past history and our lives into every experience we have.

When we just met, you told me you lived in Lyon. I immediately go to all my experiences. I've had in Lyon. The cool people I've met there, and I think – Oh, I’m going to like this guy – he’s from Lyon, he’s cool. It's weird how our minds do that in a firing second, right? But when it goes the other way, it's real trouble. If for some reason you're seeing it in the negative, so it’s about trying to figure out why that is, and what's in us that's doing that.

Throughout the movie, there are these little things that you maybe saw and that you maybe didn’t. For example, did you see the poet in the doctor's story?

Yes.

Where did you see him?

He was at the birthday party.

Cool, you saw that. Great, that's unusual. When was the first time you saw the white helmet?

I’ve got me on that one.

The first time the white helmet shows up is when the two ladies are walking out of the hospital, and he walks in holding a boy. Not to give too much away, but there are a bunch of little moments throughout the film, buried in there. It’s about understanding that the first glance of things is not always the reality of the way things are. I hope that people will see the film so that they understand that life is not so black and white. And a smuggler who's maybe a really bad human being can be a really great dad. And a white helmet who's maybe really great at saving people and revered by people in his town, may not be such a great dad.

You are incredibly invested and engaged with humanitarian work and in November last year, you joined the Jordanian Air Force on aid drops over Gaza. With the benefit of these experiences and your commitment, does the promotion of a film and the cinema bubble not feel a little quaint?

(Laughs) It's an interesting experience. It all has its own place. I'm much more for action, and I'm not so good at the schmoozing, the parties and the political part of things. I'm much more about going and doing things, and letting my work speak for itself, you know? I like that Terrence Malick model where he never showed up! (Laughs) But I don't think you can do that anymore. You would end up just coming off as an asshole! That would be really dreamy for me to not do that part of it, but I also accept it for what it is.

At this stage, I recognize that there's value in the experience that I've had and I want to share it if it’s helpful. It may not always be the comfortable way for me to do it. For instance, I have not been on social media since 2005, but that is how people are consuming media now. So this year, I'm like “Okay, I’ve got to get on social media and find a meaningful way to social media to tell stories and possibly provide some help.” It’s maybe not my first choice, but I need to do it. It’s all about finding ways to grow, and learn, and evolve. I keep evolving, I hope.