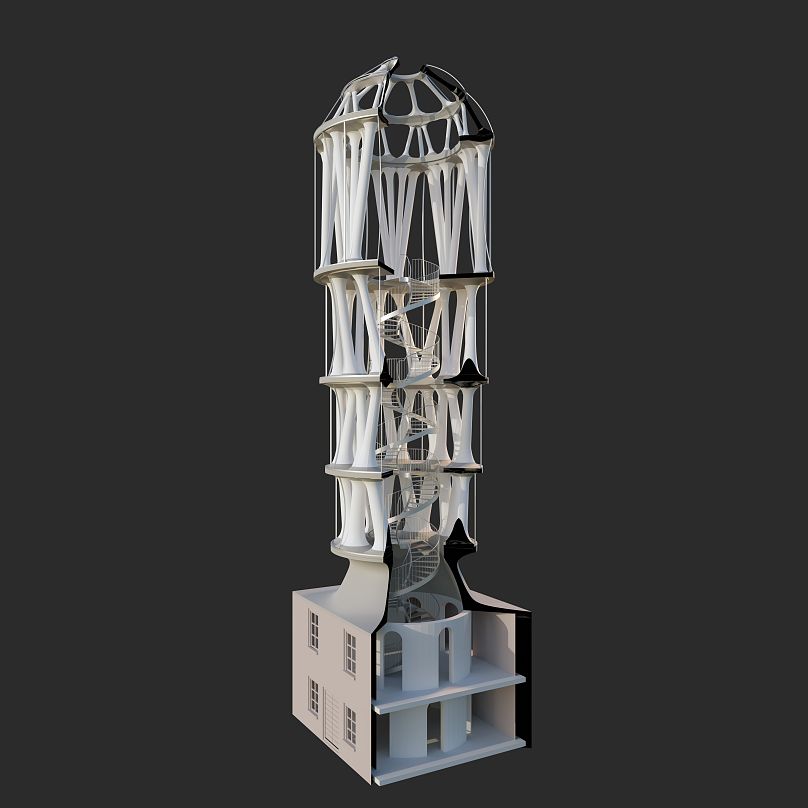

The futuristic White Tower of Mulegns stands 30 metres tall. The multipurpose cultural space is set to open in June, becoming the tallest 3D-printed structure in the world.

In digital projections, the White Tower of Mulegns looks like something straight out of a science-fiction film.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Surrounded by the snowy peaks of the Swiss Alps, the wispy ivory tower rises up from a valley like an ancient tree. Much like a tree, its structure is strong enough to withstand the cold winters and powerful winds that characterise the mountain pass.

Equal parts concert hall, art installation and monument, the 30 metre-high abstract construction will become the tallest 3D-printed structure in the world upon completion, which is scheduled for June.

The “Tor Alva” project began three years ago as an initiative to revive the declining villages of the Julier Pass, which was once an important point of transit between Northern and Southern Europe.

The population of Mulegns, the village where the tower is being installed, has drastically plummeted since its activity peaked in the mid-19th century. Today, only around 16 people live there, and many buildings sit abandoned and empty.

Nova Fundaziun Origen, the region’s cultural foundation, proposed that an architectural wonder like Tor Alva could hold the secret to the area’s revival, inspiring people to stop and visit, catch a performance and maybe even spend a couple nights.

An exercise in creative teamwork

A feat of modern construction, Tor Alva is the product of years of work and collaboration involving dozens of engineers, material specialists and researchers.

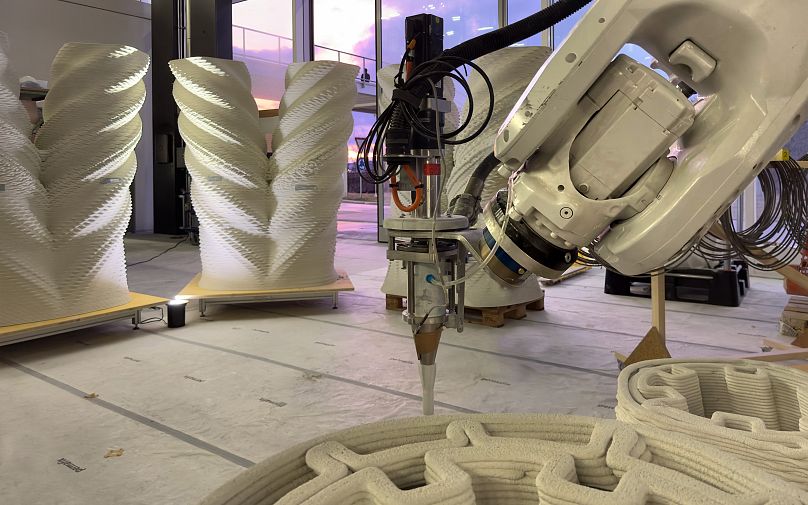

The tower is made from concrete that is 3D printed using an extrusion process pioneered at the Department of Building Technology (DBT) at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH). in Zurich.

It was designed by architects Michael Hansmeyer and Benjamin Dillenburger, both pioneers of computational design and digital fabrication.

Although 3D printing of concrete has existed for years, this is the first time that the process has been able to integrate rebar, or steel reinforcement rods, giving the structure the stability needed to stand tall, according to Hansmeyer.

“Up until now, there was never any rebar integrated into the concrete,” Hansmeyer told Euronews Culture. “We’ve been able to integrate for the first time rebar into this concrete extrusion process, which allows us to build very, very high.”

The building is made of 32 prefabricated columns, which can easily be printed and assembled on site. It has five levels, which become brighter and more airy as one climbs the winding staircase, reaching the domed performance venue on the very top.

The performance space can welcome 45 visitors and features a panoramic view of the surrounding mountains. The tower’s facade will feature a removable, translucent membrane to protect visitors from cold winter weather.

At the start of February, the printing process began for the first eight columns, which will make up the lower floor of the building. It will take a total of 900 hours for all of the elements to be 3D printed.

New freedoms, new challenges

This new way of building comes with a host of new freedoms when it comes to design, as well as unique challenges for structural integrity.

The shape of the Tor Alva, with its branching columns and wave-like surface, could never have been made with traditional building methods, Hansmeyer said.

“Architecture over the last 100 years has been dealing so much with standardised forms, which have usually been strained at 90 degree angles, surfaces that are not articulated but are kind of flat,” Hansmeyer said. “By using this 3D printing technique, we can reintroduce an ornament, or non-standard curvatures at no cost because the robot doesn’t really care whether it prints a straight line or an ornamented one.”

“For us architects, this freedom of design is super exciting,” he added.

Each column in the tower will be unique, with its own surface structure and ornamental layer acting like a fingerprint. In a way, Hansmeyer says, modern technology can actually bring back a certain artisanal aspect to building, which has been mostly absent from contemporary constructions.

“It's almost like going back in time before industrialisation and mass production and assembly line production came along, back to a time when there was more of an artisanal production,” he said.

But the design was also informed by technical constraints, Hansmeyer added. The tower was initially drawn with vertical columns, which were swapped out for the current Y-shaped ones after researchers found they could better withstand the loads brought on by winds and activities.

A more ecological way of building

Another advantage to 3D printing concrete is that the structures have a smaller environmental impact, according to Hansmeyer.

Traditionally, building concrete structures requires formwork, or frames that are used to give the poured concrete its shape. Concrete structures have also been made from solid blocks or columns, a technical constraint that maintains the structural soundness of the building.

But 3D printing offers a unique, more minimalist alternative – formwork is no longer necessary, saving on materials, and the amount of concrete needed to build a solid structure is reduced because the robots involved in 3D printing can print just the outer shell of the building.

The problem of the building’s end-of-life, which is one of the most polluting aspects of the building industry, is also solved by the fact that the structure is easily disassembled.

“This tower is all built in a modular way, and things are simply screwed together,” Hansmeyer said. “So we can unscrew the different parts and we can disassemble the tower to give it a second use or a second life, either as a tower somewhere else, or to make the components part of another project in the future.”

The Tor Alva will stand in Mulegns from June 2024 until it is disassembled in 2029, after which it will continue its journey elsewhere.