14 December 1911: Roald Amundsen wins the race to the South Pole

In the early 19th century, European explorers started to visit the southern polar continent of Antarctica. It’s been suggested that Polynesian cultures may have visited Antarctica hundreds of years before any Europeans made the trek, but these accounts are disputed.

The first definitive sighting of Antarctica was by William Smith in 1819 when he sighted land south of the parallel 60° south latitude. Two years later, Captain John Davis, an American sailor is believed to have set foot for the first time on Antarctica.

Over the next century, expeditions abounded to try and chart the Antarctic circle. British expeditions began in 1898 to reach the southernmost pole of the planet. These were followed by similar expeditions by Germans, Swedish, and French explorers.

Finally, the ultimate goal was set. In 1910, two rival expeditions set out to reach the South Pole. The second was Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen team on the Fram ship with Brit Robert Falcon Scott’s expedition on the Terra Nova having set off months beforehand.

Amundsen left Oslo with the Fram on 3 June 1910. They arrived at the edge of the Great Ice Barrier (now known as the Ross Ice Shelf) over half a year later on 14 January 1911 where they established a base camp called Framheim.

After an unsuccessful first attempt, Amundsen and four other men left Framheim on 19 October to begin their journey south. After a month spent climbing glaciers in the Transantarctic mountains, the crew began their march to the pole. On this day, the 14 December 1911, Amundsen planted the Norwegian flag on the South Pole, the first human to officially make it there.

Amundsen’s journey was a success and his team made it back to Framheim before returning to Norway to universal acclaim. If only the same could be said of Scott’s British expedition.

Scott’s crew had camped with Amundsen’s at Framheim and got on well with each other before the two teams set off on their journeys to the pole. They left the base camp on 1 November. Of a team of 65 that had originally set out on the expedition, only five were part of the final journey.

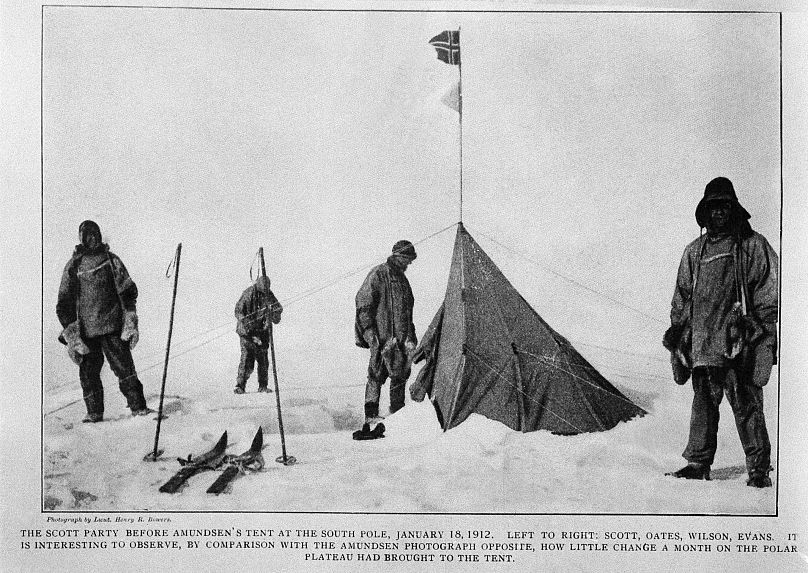

The Brits struggled through the difficult terrain, losing many of the ponies they had brought while their mechanical sledges broke down. Eventually they made it to the pole, only to find out they had been beaten. On 17 January 1912, Scott’s team saw the Norwegian flag of Amundsen’s.

Tragedy struck on the return journey. Demoralised, the crew were slowly picked off by the inhospitable cold. Edgar Evans was the first to die, collapsing after a fall on 17 February.

After further setbacks, Lawrence Oates, who was suffering from frostbite and slowing the team down, sacrificed himself by leaving his tent to face the blizzard on 17 March. Oates hoped that the team would have better survival chances without him. He was 32.

Scott and his final two companions Edward Wilson and Henry Bowers, are believed to have died on 29 March 1912 in their tent.