From normalising populist rhetoric to objectifying women on TV, Euronews Culture takes a look at how the 'Cavaliere' transformed Italy’s cultural and social landscape.

The curtain has closed on the life of Silvio Berlusconi, the three-time Italian prime minister and media titan whose time on earth felt more like the plot of a Verdi opera – or even one of his TV channels' soap operas – than anything approximating that of any other politician.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

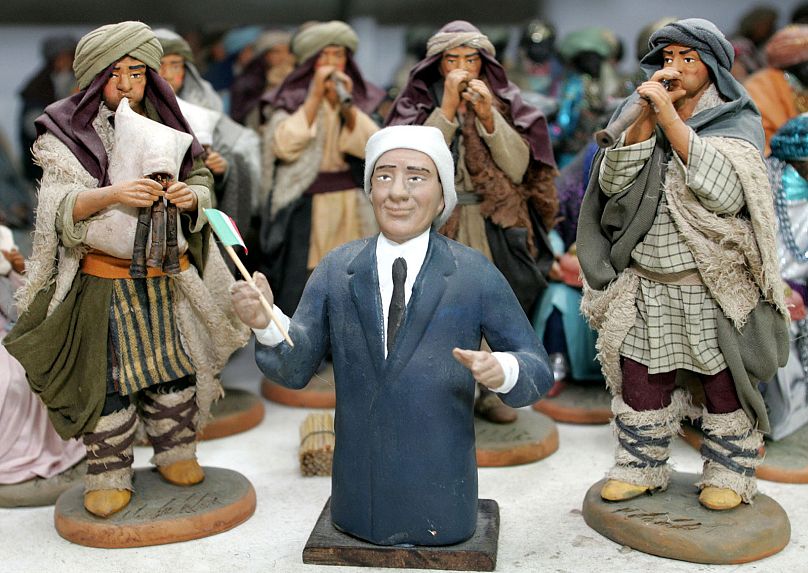

Much has been made of il Cavaliere ("The Knight", as he was nicknamed) and the sleuth of scandals, intrigues, and legal vicissitudes he has left behind. But it was Berlusconi’s transformative impact on Italian society and culture that has been arguably the most noteworthy — and controversial — part of his legacy.

Berlusconismo: 'Cancer' or 'revolution'?

Berlusconi's arrival into Italian politics came in the midst of years of turmoil which had ransacked the country’s party system, and left the political landscape with a void - one he was swiftly able to fill.

Most commentaries on Berlusconi have consequently tended to look at his impact after his so-called discesa in campo ("descent into the field", borrowing from football jargon) in 1994, and how he led four right-wing governments which brought together both neo-fascist forces (to which current PM Giorgia Meloni belongs) and the regionalist Northern League.

But as the owner of a business empire which had three top private TV channels, a newspaper, publishing house, theatre and the world-renowned A.C. Milan football club, Berlusconi had Italy under his chokehold since the 1980s, well before his political career could spread its wings.

The mogul’s Mediaset channels, which offered an alternative to the country’s state-owned RAI network, flooded the Italian media landscape with a very new brand of television. Glossy, gaudy, and gossipy, they exposed the Italian public to American soaps — Dynasty being the most prominent among them — and were dominated by lowbrow talk and variety shows, namely Striscia la notizia, presented by scantily-clad showgirls (known as veline). Clothes were looser, the language cruder, and such an erosion of certain public mores left a profound mark on the nation’s image, changing the format of national TV networks and the public’s everyday vernacular and aspirations.

Indeed, such a new cultural climate ended fuelling the aspirations of countless Italians, who dreamed of a lucrative TV career within one of his networks.

"Without TV, you couldn’t do anything," said Lele Mora, one of Italy’s best known talent agents, a Berlusconi aide, and convicted pimp. “It’s a magic box... People see you from home, and you become popular."

Berlusconi would eventually wed his media visions to his political ambitions, pioneering what came to be described as il Berlusconismo, or "Berlusconism".

Blurring the line between politics and entertainment, and treating his voters as consumers, this signalled the start of a new, kitschy – campy, even – approach to politics which had hitherto been alien to Italy's rather stuffy political establishment. Even the name of his first party – Forza Italia, loosely translated as "Onwards, Italy" or "Go Italy!" – directly borrowed from the language of football stadium chants.

The epitome of Berlusconi’s "pop political" style came in 2008, when he released an electoral TV campaign titled "Thank Goodness for Silvio!" (Menomale che Silvio c’è), showing a crowd of singing, devoted followers which make even Kim Jon-Un blush.

"There is no doubt in my mind that [Berlusconi’s] most profound impact was on Italy’s national popular culture," noted Italian journalist and documentary-maker Annalisa Piras while speaking to Euronews Culture. "Today, a quick zapping through Italian TV news is clear evidence of the Berlusconi effect".

Such an impact is still felt in the present-day, which to Piras is confirmed by the "football chanting, the hagiography and the simultaneous broadcast on 20 TV channels", of the ex-PM’s state funeral, held in Milan last Wednesday.

‘I love beautiful girls’: The public objectification of women

Il Cavaliere 's controversial relationship with women, both in his public and private spheres, has been a prevalent theme of his life.

Berlusconi claimed to "love women" and "beautiful girls", although such loves were intertwined with scandal (namely sordid "bunga bunga" party rumours) and even landed him in legal trouble. Exotic dancer Karima El Mahroug or "Ruby the Heartstealer" may have stolen his heart, prosecutors claimed back in 2010, except it came at a price — at 17, she was under the legal age of prostitution. He was eventually cleared of all charges.

It was Berlusconi’s casually flirtatious attitude towards women both in politics and on his media network, nevertheless — his constant comments praising the "beauty" of female right-wing politicians and body-shaming of those on the left, for instance — that critics see as having had the most insidious social impact.

Moreover, the late prime minister set up something of a showgirl-to-politics pipeline, with several former starlets – from former Equality Minister Mara Carfagna to regional councillor Nicole Minetti – being afforded sought-after positions within his party. According to his detractors, it was more of a bedroom-to-politics pipeline, with accusations swirling about how he had allegedly slept with some of the politicians in his party.

Berlusconi did, at least, officialise the relationship with one of his party members. Marta Fascina, 33, is a Forza Italia MP and was his girlfriend from March 2020 until his death.

Beyond Berlusconi’s own personal relationship with the women in his party, critics have accused him of fostering a cultural and media climate where women would be increasingly pressurised into conforming to conventional beauty standards, or even resort to cosmetic surgery, in order to succeed in their careers.

"[Berlusconi’s] objectification of women, in his personal life and in his media, has arguably set back equality in Italy by decades", Piras remarked. "The shameless objectification of women, whose value was always made conditional to their looks, has deeply poisoned and permeated public attitudes and personal perspectives on femininity".

"I remember growing up in a country where there were several authoritative female middle-aged newsreaders," she added. "Today there are none."

Barbara Serra, a British-Italian journalist and author of award-winning documentary Fascism in the Family, echoes Piras’s comments, although she sees Berlusconi’s impact on women as complex, and noted how the ex-PM did not only "champion" former showgirls’ political careers — Meloni herself being the prime example. Serra's overall assessment, nevertheless, remains negative.

"He hugely damaged young women, and also young men. He made money off of their objectification, and turned women into something to be bought", she told Euronews Culture.

"And ultimately, the scandal that brought him down - which he won on appeal - wasn’t that of his bunga bunga parties, but that he had allegedly paid for sex with a woman under the legal age of prostitution".

Loaded gaffes: How Berlusconi’s jokes normalised far-right narratives

If Berlusconi made a name for himself as the unparalleled master of one skill in particular, it’s his impeccable ability to say the wrong thing at exactly the wrong time.

The ex-PM’s gaffes, from playing peek-a-boo with former German Chancellor Angela Merkel to visibly irking the typically stoic late Queen Elizabeth II, left the public guffawing and had subeditors finding headlines written for them.

But such behaviours and comments had political undertones that had wider social and cultural implications.

His many faux-pas had racist undercurrents, a deeply problematic issue in a country that has yet to fully reckon with its fascist colonial history.

For example, in 2010, he made a joke about Jews in concentration camps that even garnered the condemnation of the Vatican, while getting in hot water two years prior for calling then-US President Barack Obama "suntanned".

His gaffes exploited sexist attitudes to further enforce prevailing homophobic prejudice. "It's better to like beautiful girls than to be gay," he quipped at a motorcycle show back in 2010.

They also referenced a particularly unsavoury, longstanding friendship with Russian President Vladimir Putin, such as when Berlusconi gifted him a widely mocked duvet cover for his 65th birthday. Putin’s invasion of Ukraine last year and violations of human rights did not deter the Cavaliere from expressing his love for his chum, claiming he sent him "bottles of Lambrusco" and a "sweet letter". Coalition colleague and current PM Giorgia Meloni was decidedly unimpressed.

His comments further normalised far-right rhetoric and narratives, brandishing opponents as “Communists” and supporting the italiani brava gente ("good Italian") trope, the idea that Italy was a victim, rather than a perpetrator, of Holocaust war crimes.

"Mussolini never killed anyone", he told right-wing British magazine The Spectator in 2003. "Mussolini exiled people on holiday".

But most of all, Berlusconi’s almost comically grandiose victim complex, and the gaffes that came along with it, wrote the playbook that populist politicians would eventually borrow a page from.

Well before Donald Trump was banging on about "fake news", Berlusconi was already finessing the art of performative victimhood and constructing anti-establishment narratives.

"I am the Jesus Christ of politics," he was quoted as saying back in 2006. "I am a patient victim, I put up with everyone, I sacrifice myself for everyone."

"He started saying the unsayable, not caring about the impact of his words", noted Serra. "He was not scared to be divisive -- you always have to win against someone."

A life on the silver screen

For a public figure who was so much larger than his 86 years of life, it comes as little surprise that Berlusconi would himself garner cultural icon status and obtain silver screen treatment.

Much of this treatment was decidedly unflattering. Acclaimed documentaries such as Videocracy (2009) and Girlfriend in a Coma (2012) dissected his political impact and indeed became pelliculae non gratae in an Italy heavily under Berlusconi’s control, as they found themselves facing censorship and had their releases thwarted.

As for fictional depictions, two prominent examples include Nanni Moretti’s The Caiman (2006) and Paolo Sorrentino’s Loro (2018). The former’s film-within-a-film portrayal of a grotesque, money-hungry politician best encapsulates the legacy Berlusconi left behind: upon his court conviction, hordes of rabid supporters angrily assault the “leftist” judges upon leaving the tribunal.

The parallels with crowds of Italians chanting against “Communists” outside Berlusconi’s funeral are evident - and a tangible sign of the new political language and culture Berlusconi leaves behind.