In an ambitious plan involving hundreds of international scholars, the Republic of Uzbekistan is scouring the world for literary artifacts from the nation’s history. Earlier this week, in Tashkent, a conference involving domestic and foreign scientists, museum curators and conservators mapped out a four-year road map which ultimately will engage up to 1,500 scholars in 90 separate projects worldwide to uncover and document Uzbekistan’s past.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

For over 3,000 years, the territory now called Uzbekistan has been a crossroads for wave after wave of conquerors, traders and migrants – Persians, Genghis Khan’s Mongols, Turks, Alexander the Great’s Macedonians, Muslim Arabs and, ultimately, Russians all had their moments. All left their mark, some in architecture but others in science, literature and the arts. There was Ibn Sina, known in the West as Avicenna, one of the most significant physicians, thinkers and writers of the Islamic Golden Age, and the father of early modern medicine. Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī produced vastly influential works in mathematics, astronomy, and geography. And Mīrzā Muhammad Tāraghay bin Shāhrukh, best known as Ulugh Beg, a Timurid sultan, was an influential astronomer and mathematician.

Over the years, many of the most prized parts of this legacy wound up in state and private collections elsewhere in the world. Shortly after taking office in 2016, President Shavkat Mirziyoyev decreed that these artifacts should be found and replicated, with the facsimiles brought home to Uzbekistan.

Thus began a worldwide search, assisted by a growing cadre of domestic and international scientists. In 2017, an international conference held in Tashkent and Samarkand formally agreed to establish a World Society for the Study, Preservation and Popularization of the Cultural Heritage of Uzbekistan. The Society began the task of contacting international museums and libraries where originals were kept.

Among the first finds was the Katta Langar Qur’an, one of the earliest written copies of Islam’s most holy book.

“Every one of the documents we have found has a story and often a mystery,” says Firdavs Abdukhalikov, head of Uzbekkino, the national film agency, and Chairman of the World Society. “But the Katta Langar Qur’an has some special mysteries.” Captured in what is now Saudi Arabia by the famous Turco-Mongol conqueror Amir Timur – known in the West as Tamerlane – the manuscript was first transported to Samarkand where it became enmeshed in the troubled history of the mystical Sufist branch of Islam.

Parts of the document wound up in different hands, with 81 pages landing with the St. Petersburg Institute of Oriental Manuscripts in Russia. Twelve pages were found at the Spiritual Directorate of the Muslims of Uzbekistan in Tashkent. A number of other pages were located elsewhere in Uzbekistan, including the little mountain village of Katta Langar, where Sufi followers had hidden some of the missing pages. Sadly, a further 100 pages remain missing.

In 2018, 100 copies of the manuscript were printed and distributed to museums and libraries around the world. President Mirziyoyev ordered one copy to be taken to its original homeland, Saudi Arabia, where it was officially presented to King Salman.

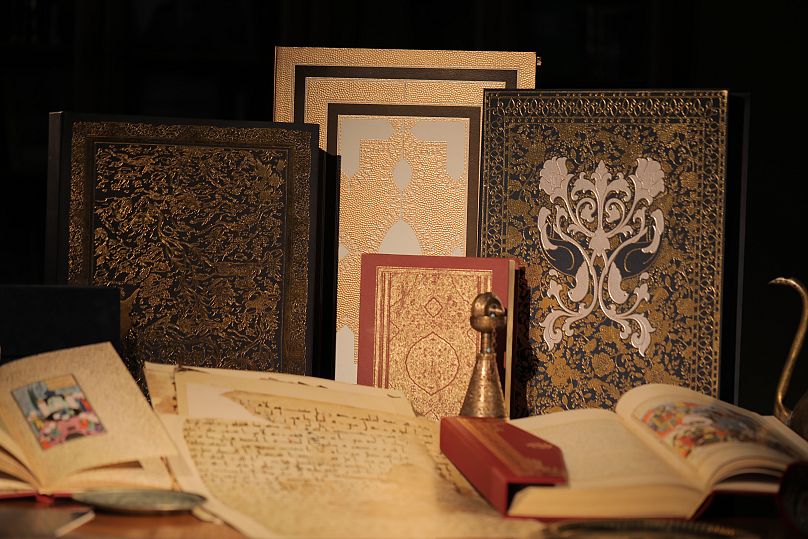

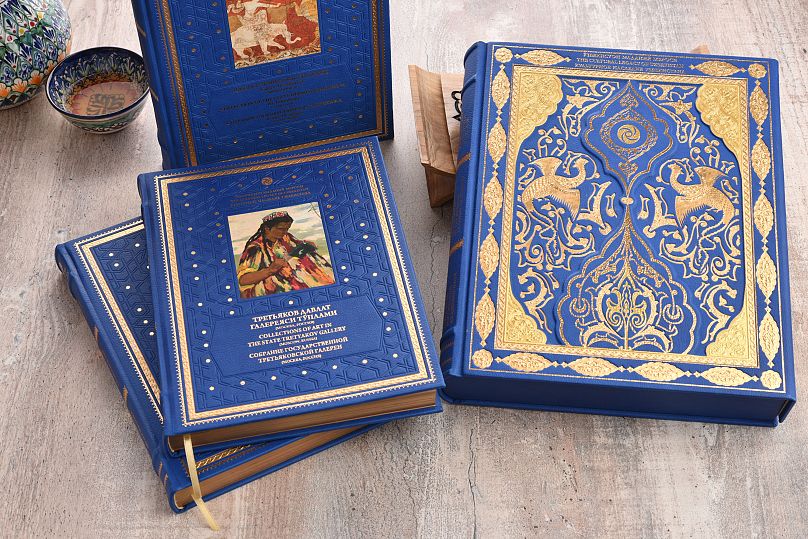

There are now 35 printed and bound books containing facsimiles of famous manuscripts which have been located internationally and painstakingly replicated. The growing collection can be found in libraries and museums across Uzbekistan.

The fabled 14th Century emperor Timur figures prominently in many of the stories behind these manuscripts. Known as Tamerlane (“Tamer the Lame”), the Samarkand-based ruler captured international imagination for his military conquests, inspiring western writers as varied as Christopher Marlowe and Edgar Allan Poe to write him into their works, and the composer George Frideric Handel to pen a three-act opera titled Tamerlano.

But Timur was more than a warlord. His success in the battlefield permitted him to bring hundreds of intellectuals – artists, scientists and writers – to Samarkand. They contributed to what is known as the Timurid Renaissance spanning the late 14th, the 15th, and the early 16th centuries, roughly in parallel with the Renaissance then flourishing in Western Europe.

The hope in Uzbekistan is that the revival of Uzbek intellectuals’ literary legacy will help inspire a new renaissance. “Uzbekistan President Mirziyoyev’s plan is that the atmosphere of enlightenment, religious tolerance and humanism which blossomed in ancient times will give rise to another era of intellectual vigour, openness and progress,” according to World Society chairman Abdukhalikov. “We are learning about our own history from the world,” he says.

He cites the example of “Zafarname” (“The Book of Victories”) by the Persian scholar Sharaf ad-din Ali Yazdi, a biographical work about Timur’s rule housed at the British Library in London. The book was commissioned by Timur’s grandson Ibrahim Sultan and is beautifully illustrated with a series of miniatures by famous Uzbekistan artists.

The World Society’s lavish reproductions were presented at the organisation’s annual conference held this week in Tashkent, drawing on source material kept in museums in the Czech Republic, India, US, Canada, Italy, Turkey, Poland, UK and Japan, as well as in Uzbekistan’s own State Museum of History and the al-Biruni Institute of Oriental Studies of the Academy of Sciences. Reprints are being distributed among local institutions.