The decisions policymakers make now will determine whether or not Europe can invest in solutions to the environmental, economic, geopolitical and social challenges we’re facing, Ludovic Suttor-Sorel writes.

As EU financial ministers and Members of the European Parliament engage in heated discussions on reforming the European fiscal rules ahead of next year’s election, crucial questions emerge.

How concerned should we be about European public debt? Would investors be willing to support EU public investment? The answers are pivotal in deciding between curtailing spending or boosting investment.

There is a huge funding gap in Europe — each year until 2030, we need €520 billion to meet our environmental and energy objectives, €125bn for our digital priorities, €142bn for social infrastructure such as hospitals and schools, and up to €190bn to maintain other public infrastructure, including roads, buildings, bridges and ports.

This funding gap is hurting our competitiveness, and it’s jeopardising the well-being of future generations.

Recognising the public good nature of many of these investments, a substantial portion must be funded through public budgets.

Whilst reprioritising public spending and improving taxation play a role, debt financing is vital to distribute the cost across generations benefiting from these investments.

Deactivating debt brakes

Failure to account for this reality in the review of Europe’s fiscal rules would be shortsighted, especially in light of recent developments in Germany.

To balance fiscal discipline with rising energy costs and investment needs, Germany established extrabudgetary funds amounting to 9% of its GDP — the so-called Sondervermögen.

However, on 15 November, the German constitutional court deemed the government's 2022 decision to reallocate €60bn of unspent COVID-19 crisis debt to a new climate fund to be used in subsequent years as unlawful.

This ruling exposed the limit of such practices and resulted in a freeze on government spending commitments, including the €200-billion Economic Stabilisation Fund. Germany's response? Deactivating its national fiscal rule, the debt brake.

Against this backdrop, why is it that several EU finance ministers remain intent on shackling the Union with fiscal rules that revolve primarily around reducing debt stocks and deficits?

Tidy arguments omitting key factors

Glossing over the significant reforms made in the wake of the eurozone crisis, some finance ministers, led by Germany, argue that higher debt and deficit reduction targets are needed in the EU fiscal rules because financial markets will react negatively to high public debt levels.

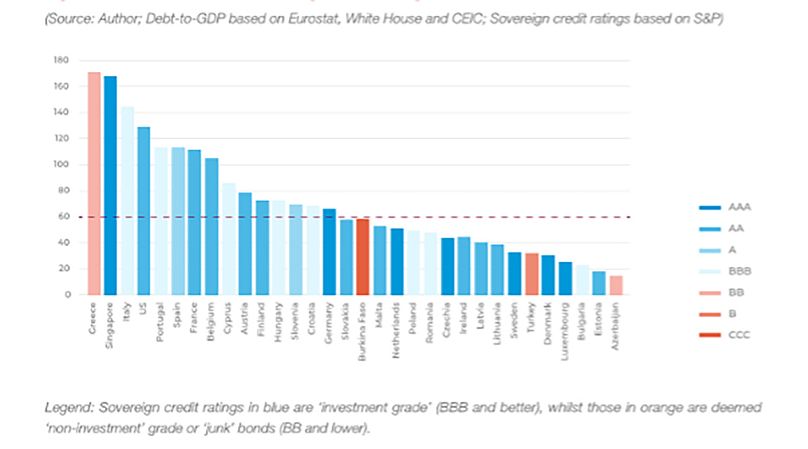

They contend that credit rating agencies, for example, Standard & Poor’s (S&P), will look at rising debt-to-GDP ratios across EU countries, downgrade their credit ratings across the board, and set the stage for the next sovereign debt crisis.

What they omit from this tidy argument is that financial market analysts don’t fixate on debt numbers alone. For instance, credit rating agencies look not only at a country's fiscal health but also its institutional and economic strength.

In fact, sovereign credit ratings have a strong correlation with economic and institutional strength (as indicated by GDP per capita, current account, and governance indicators), a moderate correlation with debt affordability (a country's annual interest payments on its debt) but no correlation with debt stock or deficit.

This doesn’t imply that investors ignore debt stocks and other fiscal indicators; it indicates that robust economic and institutional strengths can offset their influence on ratings and that these should be the priority — just look at Singapore’s AAA rating despite its ~170% gross debt-to-GDP.

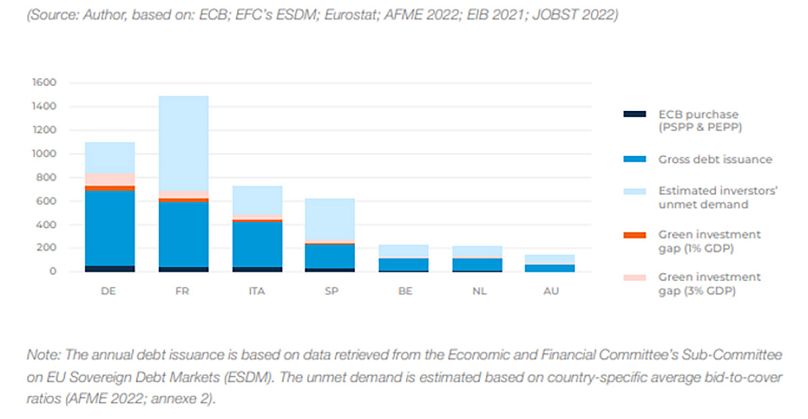

Contrary to this persisting narrative, more EU sovereign debt would actually be welcomed by many financial market participants.

Banks, pension funds and insurance companies all need high-quality liquid assets to meet their liquidity requirements, and sovereign debt securities are an appealing option.

Government bonds are the primary source of high-quality liquid assets in the euro area and currently, demand for euro-denominated sovereign debt is twice as high as supply.

A chance to move away from a punitive fiscal framework

On top of meeting investor demand, expanding sovereign debt could go a long way in reducing green investment gaps across EU member states. Investors could help finance the additional green public spending required to reach the EU’s climate objectives, estimated at 1-3% of EU GDP annually.

The current reform of the EU fiscal rules is an opportunity to move from a punitive fiscal framework to one boosting European growth and resilience.

For example, what if new rules exempted future-oriented investments from fiscal limits?

The rationale for excluding certain expenditures rests on their ability to either stimulate economic development (growth-enhancing) or mitigate future deficits due to crises (resilience-enhancing).

EU countries would include a list of future-oriented investments in their national plans, and these investments would be excluded from fiscal limits. The European Commission would then assess the quality of the investments on this list, and ensure they support the country’s debt sustainability.

What’s more, the Council of the European Union would approve or reject the list of investments, adding another layer of quality control against creative accounting.

This is one of several good proposals on the table that would ensure the EU fiscal rules prioritise future-oriented investments and reforms that boost European economic development and resilience.

The decisions policymakers make now will determine whether or not Europe can invest in solutions to the environmental, economic, geopolitical and social challenges we’re facing.

The EU needs to embrace a new way of thinking about public debt. There are debts we need, that will make Europe stronger.

Ludovic Suttor-Sorel is a Senior Research and Advocacy Officer at Finance Watch.

At Euronews, we believe all views matter. Contact us at view@euronews.com to send pitches or submissions and be part of the conversation.