With better understanding of the El Niño-La Niña phenomenon and better seasonal forecasts, industries can make better choices to adapt to future fluctuations in their activities.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

It was 0.6 degrees Celsius below the average this summer. In August 2020, data coming from the east-central Pacific Ocean was telling climate scientists that the waters continued to be cooler than usual.

“A La Niña event has developed,” said the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) in October: conditions in the air and ocean pointed to a 90 percent chance of La Niña lasting until early 2021, alerting authorities, businesses, and scientists across several continents.

So how do changes in these remote waters really get to us? And have we become more prepared to face them?

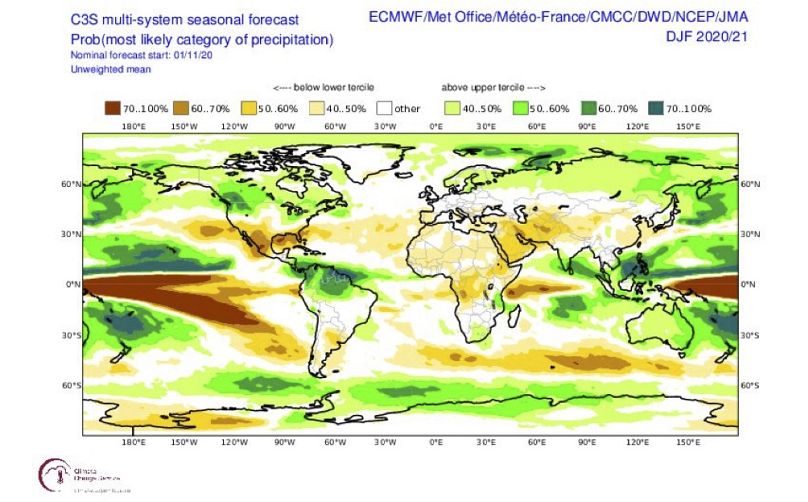

Experts say this year’s La Niña will be moderate to strong. As a result, WMO expects much of East Africa, southern parts of South America and Central Asia to receive less rain through this winter, making droughts more probable. South-East Asia, parts of Australia, the north of South America and the US might need to brace for lots of rainfall and potential flooding. In Europe, “late winter is more likely to be warmer and wetter,” according to Dr. Steve Hardiman, senior research scientist at the UK's Met Office.

Some effects have already been felt: according to the US National Hurricane Center, La Niña helped make this year's North Atlantic hurricane season extremely active, reaching the highest ever recorded number of named storms.

But first, a bit of background.

What scientists know about these phenomena

The Eastern Pacific is usually colder, while the west is warmer: A “La Niña” appears every few years when temperature changes in the upper Pacific ocean, shifts winds and sends normal conditions into overdrive. Cooler waters than usual near South America lead to less rainfall in this region. El Niño acts in the opposite way, and has the opposite effect over this region, leading to enhanced rainfall. Together they are part of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO).

“ENSO is a coupled system between ocean and atmosphere,” explains Dr. Felipe Costa, climate scientist at the International Center for the Investigation of El Niño (CIIFEN) in Ecuador. “The sea surface temperature is one variable to monitor a potential El Niño or La Niña,” says Dr. Costa, who explains one signal is a change in temperature of more than 0.5 degrees. If temperatures go down by more than that, La Niña could be on its way. “But you also need to look at sea level, air pressure, winds, etc. To monitor ENSO you need to see if both the ocean and the atmosphere are colder or warmer in tandem,” says Dr. Costa.

The single biggest thing that can change from one year to another when it comes to climate behaviour is ENSO, explains Dr. Tim Stockdale, seasonal forecasting expert at ECMWF. Since the early ‘90s scientists have deployed more instruments in the Pacific that can provide data about changes in the waters and above; today, technology allows underwater measurements down to 2,000m. “ENSO is the part we predict best and is the starting point of everything else. Once it was realised that we can predict ENSO to a good extent, that motivated the scientific community to set up seasonal forecasting systems,” Dr. Stockdale adds.

“ENSO is a cornerstone of seasonal forecasting, and it provides a lot of the predictability months ahead,” says Prof. Scaife, head of long-range predictions at the Met Office. Given La Niña’s ripple effects on global rainfall regimes – what experts call “teleconnections” – predicting it well ahead of time becomes an essential tool to help countries and businesses prepare for the possibility of extreme events… so is forecasting where La Niña might hit. “Our ability to predict the remote effects of ENSO events has improved a lot in recent years,” says Dr. Scaife. “We have now reached a point where we have the ocean and the lower layers of the atmosphere all modelled in the best forecast systems. For example, we now know that the stratosphere [the air layer above the one we live in] plays an important role in ENSO’s effects in the Atlantic-European region, like it did in 2009/2010, when it intensified and prolonged a severe winter.”

Data serving industries and businesses with more accurate predictions

Unlike your weather forecast, seasonal predictions might not tell you if you should wear your waterproofs tomorrow, but they count for other types of decisions. “Seasonal forecasts are not about predicting precisely the conditions in a particular location, but the effects of large-scale influences,” says Dr. Anca Brookshaw, seasonal and climate prediction expert at Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S). Since late 2016, C3S has provided seasonal forecasts, using data from a steadily increasing number of international climate and weather centres.

C3S integrates seasonal forecasts from these centres and provides data and predictions in a user-friendly way for experts and non-experts alike. “C3S has contributed to making climate data free and open. The requirements for data provision set out by C3S, along with the C3S Climate Data Store infrastructure, make for an easier user experience and have resulted in more homogeneous, and more easy to compare and combine seasonal forecast datasets. At C3S, we also expand the use of seasonal forecasts into predictions of direct relevance to the energy, transport, insurance industries - to name just a few.”

Forecasting what might happen in the next six months is very much deadline-driven. “We have a very precise schedule,” says Dr. Brookshaw. “For forecasts to become a valuable, integral part of the decision-making process, they need to arrive at a precise, predictable time. And, of course, the sooner they are released, the better, as this increases the warning time for potentially anomalous weather conditions.”

La Niña’s predicted higher rains in Australia will be a boon for the country’s wheat production, that might jump by more than 90 percent than last year, estimates Gro Intelligence, a consultancy. This could be Australia’s third highest wheat crop after 2016/2017 and 2011/2012, both La Niña years.

Seasonal forecasts are essential for adaptation

“Farmers, fishermen, and politicians are using this information to plan better,” says CIIFEN’s Felipe Costa. “It is known that La Niña increases some fisheries catches in Peru and Chile, but could reduce the productivity in agriculture due to drops in rainfall in some regions.”

Crop yields are only one aspect of food security, when it comes to ENSO effects, according to Dr. Weston Anderson, agroclimatologist at International Research Institute for Climate and Society (IRI). “Regions of chronic food insecurity or those already experiencing other stress are areas where ENSO may have the largest effect on food security. In the Horn of Africa, for example, we know that La Niña forces droughts that in the past have overlapped with violent conflict and political crises to cause severe food insecurity that reached famine levels in 2011. Dr. Anderson adds on a more positive note that “even if droughts cause crop failures, they don’t need to become food crises if we act quickly.”

There are also questions of how climate change effects might interact with ENSO and natural climate variability. So far, scientists still have difficulties in extracting those signals. At CIIFEN, Felipe Costa says that some climate change scenarios point to the upper part of the ocean getting warmer, which could lead to El Niño-like conditions occurring more frequently in the Eastern Pacific. At the Met Office, Steve Hardiman says IPCC models predict rainfall will become increasingly variable in the tropical Pacific. This might actually help experts make better forecasts for Europe. “This stronger ENSO-related variability appears to strengthen the link between ENSO and European winter weather, which may lead to improved seasonal predictability for European winters in future.”

Working out what remote echoes ENSO will have still needs perfecting. “Different El Niño and La Niña events show slightly different patterns and strengths,” says Dr. Scaife. “These affect the remote impacts and now that we know more about forecasting the different types of ENSO, the next generation of forecast systems will need to get these more subtle aspects correct.”