‘El Niño’s little brother’ could increase powerful storms, researchers warn.

El Niño’s “little brother” could make powerful hurricanes worse, new research has warned.

The Atlantic El Niño - a weather system involving high ocean temperatures and complex wind dynamics - is little-studied, overshadowed by the much larger El Niño climate pattern.

But fresh analysis has shed light on the weather phenomenon’s link to “the most intense and destructive” tropical cyclones.

“Atlantic Niño/Niña is potentially an additional predictor of seasonal Atlantic hurricane activity that can be used to improve seasonal Atlantic hurricane outlooks,” the authors of new research published in Nature this summer write.

So what is El Niño’s “little brother”, and how does it influence hurricanes?

What is the Atlantic El Niño?

The Atlantic El Niño involves temperature fluctuations over a vast stretch of water in the Atlantic.

Atlantic Niño is characterised by warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures in the eastern equatorial basin and weaker-than-average winds throughout the east and central Atlantic.

“Like a typical little brother, Atlantic Niño tends to follow his bigger brother, often becoming active in the summer following an El Niño winter,” oceanographer Dr Sang-Ki Lee wrote for the Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory.

The phenomenon has complex local impacts, like reducing Sahel region rainfall but boosting flooding frequency in South America.

New research suggests it could also contribute to hurricane formation.

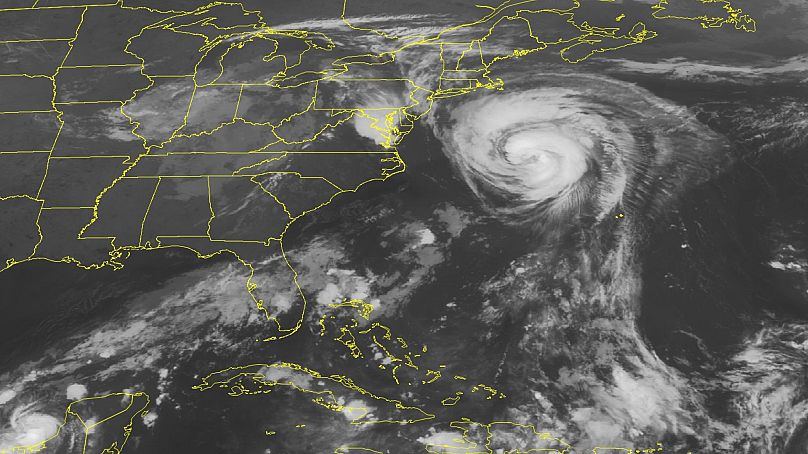

Powerful storms often form in atmospheric disturbances above Western Africa, near Cape Verde. These storms travel thousands of kilometres before making landfall in the Americas.

Cape Verde born storms account for 80-85 per cent of all major hurricanes to strike the US and Caribbean.

The longer hurricanes travel over warm seas, the more time they have to suck up the energy from these waters. Atlantic El Niño pushes up sea temperatures, and so worsens the severity of these storms.

“Such conditions increase the likelihood of powerful hurricanes developing in the deep tropics near the Cape Verde islands, elevating the risk of major hurricanes impacting the Caribbean islands and the US,” the study authors write.

What is El Niño and how is it linked to hurricanes?

It is probable that the Atlantic El Niño will develop next year, given that we are currently in an El Niño year, the first since 2018-19.

The world swings between ‘El Niño’ and ‘La Nina’ years, a climate pattern that steers weather around the world.

El Niño sees waters in the Pacific Ocean become much warmer than usual. It is caused by winds in the Pacific that push warm water eastwards as the Pacific jet stream moves south.

El Niño drives worldwide temperatures up by around 0.2 degrees Celsius overall, but has complex local implications for weather.

In Europe, El Niño usually means drier and colder winters in the north and wetter winters in the south. In the US, it generates dryer and warmer weather in northern states and intense rainfall and flooding on the US Gulf Coast and Southeast.

Monsoons in India and rains in South Africa could be reduced, but east Africa could get more rains and flooding.

El Niño can make hurricanes more powerful, because storms suck up the energy from warmer-than-average seas.

But the climate pattern also drives something known as ‘high vertical wind shear’ - how much winds change speed and direction at increasing heights - which tears hurricanes apart.This means El Niño years are generally associated with less-severe hurricane seasons.

In March, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) scientists predicted a below-average season. But high ocean temperatures means that the hurricane season - which lasts between June and November - has been deadly this year. The NOAA forecast a 60 per cent of an “above normal” hurricane season

“NOAA urges everyone in vulnerable areas to have a well-thought-out hurricane plan,” the US’s oceanography agency has declared.