Here’s a look at some of the efforts in Europe to tackle disinformation and what voters should look out for before the June vote.

Concerns are growing regarding disinformation and artificial intelligence (AI) generated content ahead of the EU elections in June.

The European Commission published recommended measures in March for digital platforms with more than 45 million EU-based users per month “to mitigate systemic risks online that may impact the integrity of elections”.

In addition, many platforms committed to the EU's Code of Practice on Disinformation "to address both misinformation and disinformation across their services,” a Commission spokesperson said.

Experts who studied previous elections in European countries noted that disinformation can take several forms with the main narratives targeting climate change, immigration, and support for Ukraine.

“Considering the very specific nature of the EU elections, we think that the situation will be broken down at the national level in most cases,” Tommaso Canetta, fact-checking vice director for the European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO), told Euronews Next.

"So, we expect the main disinformation narratives will have very national and local nuances".

Roberta Schmid, managing editor for Germany and Austria for the US-based company NewsGuard which rates news sites, agrees that false claims regarding Ukrainian refugees and climate change policies are likely to be spread.

She also noticed that “a lot of the false claims are personal, meaning a lot of it is about specific politicians”.

Fact-checkers are looking at “the risk level” but also at “how much a claim spreads” to pick the ones they will be debunking.

Deepfake audio is the main concern when it comes to AI disinformation

Regarding AI, Schmid says that it’s "an additional risk on top of the risk that was already there".

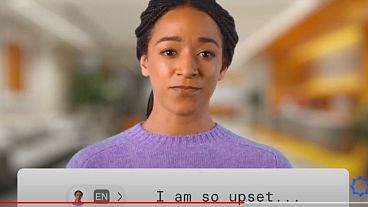

“Deepfakes has been, around for quite some time now. The big difference is that they're getting better and better. And especially now there's voice deepfakes that are really convincing,” she said.

Canetta adds that while generative AI made a technical leap in recent months, AI-generated images and videos aren’t good enough to offer entirely realistic outputs yet.

However, AI-generated audio can pass as real due to the lack of visual clues.

"It's an issue for the average user to detect the artificial origin of the content," Canetta said.

During the 2023 Slovakian elections, Michal Šimečka, leader of the Progressist party, was the victim of a disinformation campaign with a fake recording of him discussing vote-rigging with a journalist, according to multiple reports.

“This is tricky, because to debunk this kind of content, it requires time. So it can be potentially harmful for the elections,” Canetta added.

Most of the European political parties have signed a code of conduct for the elections pledging to “abstain from producing, using, or disseminating misleading content”.

The Code of Practice on Disinformation also says signatories commit to address issues such as “malicious deep fakes”. However, there is currently no foolproof system to detect them.

Experts have also warned that users should not trust AI chatbots, which are susceptible to “hallucinations” and can communicate false information in a very realistic manner.

One of the AI-fueled phenomena that is a cause of growing concern is the creation of pornographic deepfakes weaponised against female candidates.

Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni was one victim of these and is seeking €100,000 in damages, the BBC reported.

A plethora of tools to fight disinformation on social platforms

The European Commission organised a “stress test” on April 24, inviting all very large platforms and search engines.

“Participants will work through scenarios in which multiple instruments and mechanisms could be used to address incidents, such as a disinformation campaign that aims to undermine the elections,” a spokesperson told Euronews Next.

“The exercise will be used for all participants to explain their plans, procedures and policies,” he added.

Facing increased scrutiny after previous scandals, several social media platforms have taken several measures to increase disinformation monitoring.

TikTok, owned by the Chinese company Bytedance, set up an EU online election centre, adding that 30 per cent of MEPs were present on the platform.

“We work with 15 fact-checking organisations around the world that support more than 40 languages,” the company told Euronews Next, adding that the videos with “unverified content” were flagged to users and don’t appear in the “For You” feed.

Weeks after TikTok’s announcement, Meta also said that it was setting up its own operations centre for the elections “to identify potential threats and put mitigations in place in real time”.

In a separate statement, Facebook’s parent company said that it planned to start labelling AI-generated content in May 2024.

Google also stacked up its anti-disinformation task force Jigsaw and is preparing to launch a campaign across five EU countries, according to Reuters. The company also started rolling out restrictions on election-related queries asked of its Gemini AI chatbot.

The social media platform X, formerly Twitter, hasn’t made any election-related announcements.

Companies face fines of up to six per cent of their annual global revenue if they don’t comply with the Digital Services Act (DSA), which requires platforms to mitigate election manipulation.

Experts say voters should be cautious.

It’s important to check the source of the information shared, especially as doppelganger websites can be created to mimic trustworthy media, Schmid said.

“Think before sharing, see the source of the content you're about to share, see what other sources are saying, traditional media, even if sometimes they do spread misinformation, they're still the most reliable source of information,” Canetta added.

“Nourish a healthy scepticism without falling into the trap of not believing anything that you see. There should be a right way in the middle”.