There are several circulating subvariants of Omicron globally. But what are they and why are we not as concerned as WHO officials about it?

While the height of the pandemic may be over, the virus that causes COVID-19 continues to mutate with multiple variants circulating in every country.

Yet despite this, testing and surveillance have decreased, with experts urging people to keep taking the threat of this disease seriously.

"The world has moved on from COVID, and in many respects, that's good because people are able to stay protected and keep themselves safe, but this virus has not gone anywhere. It's circulating. It's changing, it's killing, and we have to keep up," Maria Van Kerkhove, the COVID-19 technical lead at the World Health Organization (WHO), told Euronews Next.

What are some of the most common COVID variants today?

All the variants circulating today are sublineages of Omicron, a highly transmissible variant of COVID-19 that first emerged two years ago.

One sublineage, EG.5, also nicknamed Eris, currently represents more than half of the COVID-19 variants circulating globally. It was declared as a variant of interest by WHO back in August.

Cases of EG.5 increased over the summer, but it was recently outpaced in the United States by a closely related subvariant called HV.1. This subvariant now accounts for 29 per cent of the COVID-19 cases in the US, according to the latest figures from the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

"HV.1 is essentially a variant that's derived from EG.5.1 (and previously XBB.1.5) that's just accumulating a few mutations that allow it to better infect people who have immunity to SARS-CoV-2," Andrew Pekosz, a professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at Johns Hopkins University in the US, told Euronews Next.

Pekosz, who studies the replication of respiratory viruses, said that these variants likely emerged as random mutations as part of the natural evolution of viruses.

According to the European Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (ECDC), XBB 1.5-like variants such as EG.5 - or Eris - are currently dominant, making up about 67 per cent of cases in EU/EEA countries.

The prevalence of another Omicron sublineage called BA.2.86 has been "slowly increasing globally," according to WHO, which recently classified it as a "variant of interest". Its sequences were first reported in Israel and Denmark in July and August.

"BA.2.86, when it emerged, was something that was really concerning to scientists because it was a variant that had a large number of mutations, particularly in the spike protein, which is the target for the protective immunity that vaccines and infections give you," said Pekosz.

Scientists think that this variant likely originated in a person with a compromised immune system which allowed the virus to replicate and accumulate mutations at a faster rate, yet it hasn’t come close to becoming dominant.

French authorities, however, recently said that most cases of BA.2.86 in the country were a new sublineage JN.1, which has been "detected in other countries but is mainly circulating in Europe and particularly in France".

It appears to have more mutations that make it more transmissible, Pekosz said.

Should we be concerned about the new variants of COVID?

RNA viruses like SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19, are known to pick up mutations at a faster rate than other viruses "because they make more mistakes and don't have the ability to fix those mistakes," according to Pekosz.

SARS-CoV-2 and its spike protein also appear to tolerate a lot of mutations, similar to what scientists see with influenza.

But so far, while scientists pay attention to these mutations, they are not seeing changes in disease severity, and the tests we use still detect the virus.

These new variants will continue to emerge and "for the most frail in society, especially those with certain underlying health conditions, they will continue to contribute to hospitalisations and even deaths," said Andrew Pollard, a professor of infection and immunity at the University of Oxford.

However, Pollard does not expect them to "reboot a pandemic" as globally, there is strong population immunity from vaccination and prior infection.

While new families of COVID-19 are “likely being generated by mutation," there hasn’t been one "as successful as the Omicron variants which are dominating," he said. “At least for now".

The worst-case scenario would be a new variant that spreads more quickly and causes more severe illness that the vaccines do not work against.

“We don't take anything for granted. We have different scenarios that we're planning for in terms of the variants and their detection,” said Van Kerkhove, who is also WHO's interim director for epidemic and pandemic preparedness and prevention.

Decreases in testing and surveillance ‘challenging’

At the moment these variants are not causing a new large surge in cases or hospitalisations, and while experts say that there is still enough sequencing for them to detect emerging variants, these efforts have decreased.

“What we've lost recently is the ability to really get a sense of the whole diversity that's present in these virus populations,” said Pekosz.

Van Kerkhove encouraged people to continue to get tested if they think they have COVID-19 because that allows scientists to track the virus and later sequence it to study possible mutations.

"If you’re not tested, you can’t be sequenced," she said.

Reductions in testing and sequencing as well as increased delays in getting the data "is very challenging for us and slows down our ability to do risk evaluations of each of these subvariants," she added.

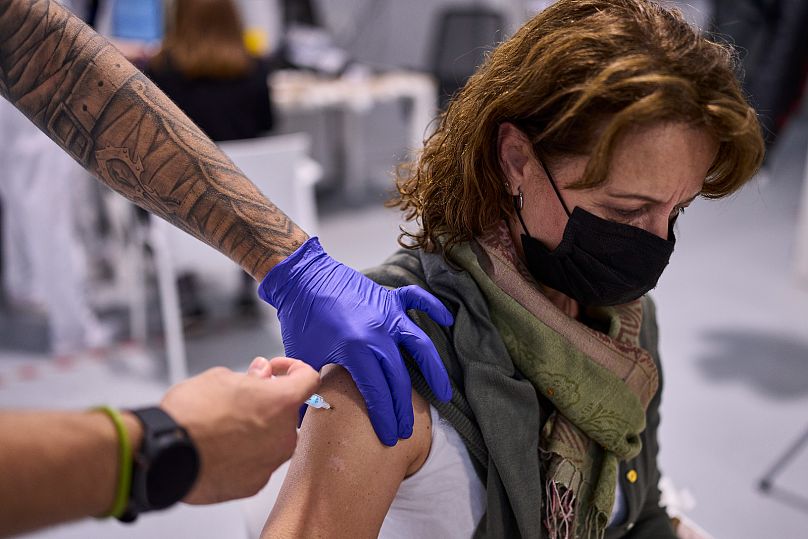

Most importantly, even as the world moves on, experts recommend that people get vaccinated, wear masks in crowds or around people at higher risk of severe COVID-19, and get tested to prevent its further spread.