2020, the hottest year on record wrapped up the hottest decade ever. Although global lockdowns have not stifled the warming climate, the global health crisis might nudge us into climate action.

Last year wasn’t business as usual. But while our livelihoods were disrupted by an ongoing health and economic crisis, our planet’s climate continued on its warming course, with particularly high levels throughout the last decade. Global lockdowns have led to slightly lower greenhouse gas emissions, while air quality improved, at least temporarily. But the world in 2020 still experienced record-breaking temperatures, and extreme weather in what experts deem now the hottest year in history, on par with 2016, according to Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) who was the first to publish such data. The World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) combining five datasets confirmed that 2020, 2019 and 2016 were the warmest years on record with minimal differences between the datasets making a clear ranking difficult. Climate change might not stumble on us taking a short break from our activities. But as we gain new perspectives on what a global crisis means, we might find fresh momentum to mitigate climate change.

Global, local and ocean temperatures continued climbing

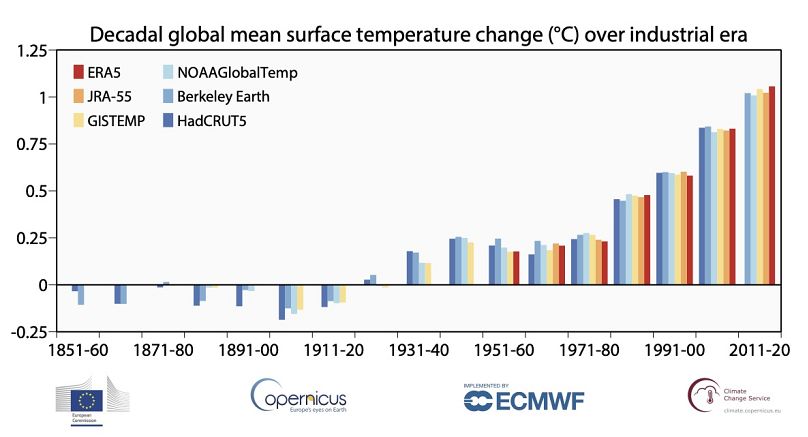

In 2020, the global climate was 0.6 C warmer than averages between 1981-2010 and around 1.25 C above pre-industrial levels, according to new data from the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) and a recent report from the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO). The year also wrapped up the hottest decade registered, of which the last six years were the warmest ever. “The temperature ranking of individual years is less important than the long-term trend, which shows the unequivocal warming of the planet as a result of heat-trapping greenhouse gases from the burning of fossil fuels,” says Dr. Omar Baddour, head of Climate Monitoring and Policy Services at the WMO.

Large regions of the Eurasian continents were particularly warmer than average. Europe’s 2020 was its warmest yet, almost half a degree Celsius above 2019 and 1.6 C when compared to the recent 30-year reference period. Temperatures in parts of the Arctic and northern Siberia saw temperature increases by more than 6 C from their long-term averages.

“The exceptional heat of 2020 is despite a La Niña event, which has a temporary cooling effect,” says Dr. Baddour. “It is remarkable that temperatures in 2020 were virtually on a par with 2016, when we saw one of the strongest El Niño warming events on record. This is a clear indication that the global signal from human-induced climate change is now as powerful as major naturally occurring climate drivers.”

Fewer greenhouse gas emissions, but concentrations still rising

Last year a flood of headlines celebrated the silver linings of global lockdowns: a drop in pollution levels and greenhouse gas emissions in some of the most industrialised areas on the planet. Concentrations of nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide and sulphur dioxides dropped across the world, as countries’ restrictions toughened. Last February fine particulate matter levels were 20-30 percent lower across Eastern China, while Europe and North America recorded similar drops throughout April. In some parts of South America, pollutant concentrations halved.

Temporary reduction in daily global CO2 emissions during the COVID-19 forced confinement. Source: Global Carbon Project

CO2 emissions also dropped, though only by 7 percent, according to the Global Carbon Project. A recent study published in Nature attributes the drop in carbon emissions in the first half of 2020 mainly to the disruptions in ground transport and energy production and less to industry and aviation. Levels bounced back though as restrictions eased.

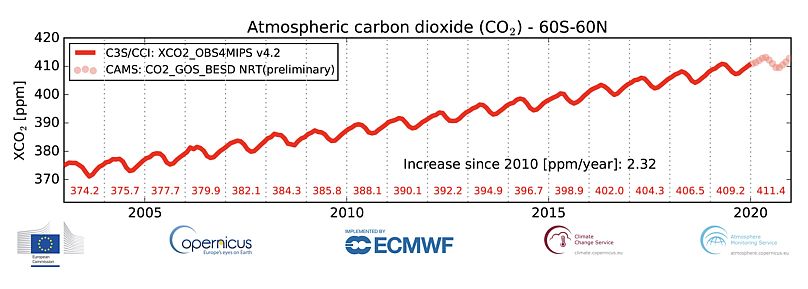

But CO2 concentrations still rose by about 2.3 parts per million (ppm), data from Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) shows. Although the growth rate was lower than in 2019, 2020 concentrations still continued to increase, confirming trends in the last decade, when CO2 growth rates ranged at around 2 ppm/year according to WMO. Dr. Gavin Schmidt, director of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, sums up what’s been happening: “COVID-related restrictions did make a difference to CO2 emissions,” says Dr. Schmidt, “but given we have put about 10 gigatonnes of carbon (GtC) into the atmosphere in 2019, and the deep oceans are only sequestering around 2 GtC, […] we are still emitting more than the planet can handle. So 2020 CO2 concentrations went up yet again.”

“The connection between emissions (or how much we put in the air) and concentration (what is in the air) is controlled by the global carbon cycle,” says Dr. Oksana Tarasova, Chief of WMO’s Global Atmosphere Watch Programme. About 46 percent of the carbon we emit stays in the atmosphere, while the rest gets absorbed by the biosphere and the oceans. But the biosphere’s uptake varies every year, boosting or decreasing CO2 concentrations by about 1 ppm, explains Dr. Tarasova. These dynamics make it harder for experts to tell the exact influence of nature from that of human activity. Some years we produce more emissions, and nature may absorb less or more of that, or we emit less, but nature also takes in less carbon. “We are talking about a rather small anthropogenic signal that can be hidden by the large natural variability,” says Dr. Tarasova.

“We will not fight climate change with a virus”

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres used those words last March to highlight that global lockdowns are not an effective, sustainable strategy to mitigate climate change. A seven percent drop in CO2 emissions is also not enough to put us on a path to net-zero carbon, many experts are warning. But this drop, alongside the urgency shown by governments in addressing the health crisis, does offer new perspectives on our approach to the climate crisis.

Some of the adaptations we’ve been forced to make during lockdowns might be sustainable in the long-run. Experts from the University of Munich and MIT claim that lockdown behaviours unrelated to the economic slowdown could be maintained. Continuing work-from-home schemes, reduced business travels, cycling to work and shopping closer to home or online could quickly slash as much as 15 percent of all pre-pandemic emissions from transport.

“What the health crisis shows is that it is possible, at least for some activities, to reduce emissions without reducing efficiency, but this should be made systemic rather than just episodic,” says Dr. Vincent-Henri Peuch, head of Copernicus Atmospheric Monitoring Center (CAMS). He adds that more of the general public is becoming aware that more rapid, more aggressive climate mitigation actions from their governments would be needed. “Relief on the climate system through curbing CO2 concentrations growth will take a long time, and in the meantime things can only deteriorate… so fast action is more than ever required,” said Dr. Peuch.

2020 economic slowdowns, an opportunity for a climate resilient restart

Global economic downturn is not favouring climate mitigation policies, says the WMO, but it can provide a clean slate for rebuilding greener economies. After the pandemic, stimulus measures bailing out fossil fuels and supporting a business-as-usual growth could boost emissions, as it happened in some countries after the 2008 financial crisis. Financial packages that push growth onto a greener path, while supporting GDP and employment during our recovery from COVID would help us leverage that clean slate. “Failure to tackle climate change may threaten human well-being, ecosystems and economies for centuries. Governments should use the opportunity to embrace climate action as part of recovery programmes and ensure that we grow back better,” said WMO Secretary General Petteri Taalas.

So far, governments around the world have pledged $12 trillion in recovery packages. It is still unclear how much of that will go towards climate-friendly investments for long-term growth. Last year in June, Bloomberg estimated only 0.2 percent of that amount was for climate priorities, though discussions about the EU’s Green Deal and green recovery ambitions in the US and other major economies are ongoing. But one recent analysis from Imperial College points out a clearer price tag for taking meaningful climate action in the near-term. Experts think that if every year, countries would invest just 10 percent of the $12 trillion in “climate-positive recovery plans for the global energy system”, we could be on track to meet the Paris Agreement goals.

Last year wasn’t business as usual. It was a wake-up call about the impacts of a global emergency, and about how fast and decisive we can be to solve it. The time to apply these lessons to our climate crisis is near.