About nine million species of animals and plants are exposed to changes in the global climate. Monitoring how climate change affects wildlife and ecosystems has become critical for directing conservation measures where life is most at risk.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

“The living world is a unique and spectacular marvel,” comes in the baritone voiceover of David Attenborough, as images of wildlife pouring into a savannah landscape run on the screen. “If we act now, we can yet put it right,” adds the UK naturalist and broadcaster, referring to how we can still save and protect the animals and plants we’ve endangered throughout centuries of changing the natural world.

We stand to lose about 18 percent of the world’s plant species and another 22 percent of mammals, if the global average temperature will increase by 2°C by 2100, experts estimate. With climate change emerging as one of the biggest drivers of biodiversity loss, policy makers looking for conservation solutions need to know how different future climates will affect species. Yet, are our science and methods already accurately helping us predict how species will react to changing habitats and climate?

Scores of scientists, labs, start-ups, and governments are working remotely and in the field to untangle how global and local climates behave and how they might shift by the end of the century. At least a quarter of the world’s estimated 8.7 million species might already be on the move, experts have warned, pushed out of their habitats by the changing climate and human activities. The same factors could bring to extinction about 1 million animal and plant species in the next decades, says the IPBES report; the study also stresses that climate change poses growing risks for species as it doesn’t operate solo - its interactions with land-use change and overexploitation of marine resources amplifies negative effects on wildlife.

It’s not just the species that we stand to lose. Losing biodiversity can significantly affect our health, if the services nature provides no longer fit our needs, warns the World Health Organization (WHO). As plant species vanish, that lack of plant gene diversity can make food crops more vulnerable to pests and diseases, undermining global and local food security; it also means the pool of medicinal plants that could provide new treatments for human diseases could shrink.

Each species of plants and animals thrives only in certain climate conditions, in what scientists call a “climate envelope”. “It’s a comfort zone,” says Dr. Samuel Almond, Climate Applications officer at Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S). “If the temperature or rainfall changes outside that zone, say for a tree, if these species can’t adapt to those changes, then it will impact its growth and reproduction.” Changes to their habitat’s climate can hinder wildlife and plants’ biological mechanisms or push them into migrating to places with conditions similar to their preferred ones. Others can adapt and survive the altered conditions.

Other factors might interfere too. Often climate change doesn’t affect wildlife directly, according to Dr. Mark Urban, associate professor at the University of Connecticut. “Many of the climate impacts on biodiversity happen through species interactions. A species might not be declining because it can’t survive the heat, but maybe because its food has disappeared or because there’s a new predator or a new disease that has arrived with the change of temperature,” Dr. Urban tells Euronews. “We may want to focus on the species that are critical in particular food webs, that are often also sensitive to climate change. They are often top predators, and as they play a keystone role in the ecosystem, any climate impact on them will have a huge effect on other species.” “We don't know how good we are at forecasting biodiversity responses under climate change,” says Dr. Urban. “We’re currently using correlations or statistics to predict the future; those statistics can work for a period of time and for some species, but when you have something more complicated, it becomes pretty easy for those predictions to fall apart. The challenge is to improve predictions, building models using biology, rather than statistics,” Dr. Urban explains. The Connecticut-based scientist says that including species’ natural processes – i.e. birth, death, how they move, how far – when modelling climate impacts on biodiversity will provide a more rounded picture of what the future holds for millions of species. It will also help people prioritise conservation for those species needing it most. “Without knowing which species can adapt and which can’t, you might spend a lot of resources on those that can adapt, and let others decline,” says Dr. Urban. But climate information that can help researchers and policy makers understand how climate change might redistribute species and their habitats is becoming increasingly available. “We’re creating a suite of indicators built specifically for the biodiversity community to use in biological modelling and monitoring,” C3S’s Dr. Almond explains about the Global Biodiversity Service.

“The data in the Global Biodiversity Service looks into the expected climate conditions in the decades to come,” says Professor Koen de Ridder from the Flemish Institute of Technological Research (VITO), which works closely with C3S on the project. “Among the difficulties in linking climate indicators to species is that climate is not the only aspect affecting species abundance and habitat suitability. Yet, the IPBES expects that, for many areas and species, climate will become a dominant driver in the future. This is precisely what our Global Biodiversity Service responds to, by casting a glance into that climatic future.” de Ridder explains that the service will help the conservation community and others to better measure climate risks to species, include climate factors in conservation projects and find solutions to concrete threats, such as finding where to relocate endangered species.

The climate-biodiversity indicators in the Global Biodiversity Service measure the impact of temperature, rainfall and other land, ocean, and atmospheric variables not just on species’ geographical ranges, but also on their fitness and reproduction, and on the ecosystem services they provide. “All indicators are at global scale, but we also provide climate projections at regional and local levels,” Dr. Almond explains. Users will be able to use the 80 indicators and incorporate them in their own models, according to C3S. The platform can also provide maps showing how climate envelopes for species might evolve from the present up to 2100, if information on species’ environmental tolerance is available. “One will be able to see where species will be under pressure, where they are more likely to survive, which trees are susceptible to climate change, which types should be planted to mitigate or adapt to climate change,” adds Dr. Almond.

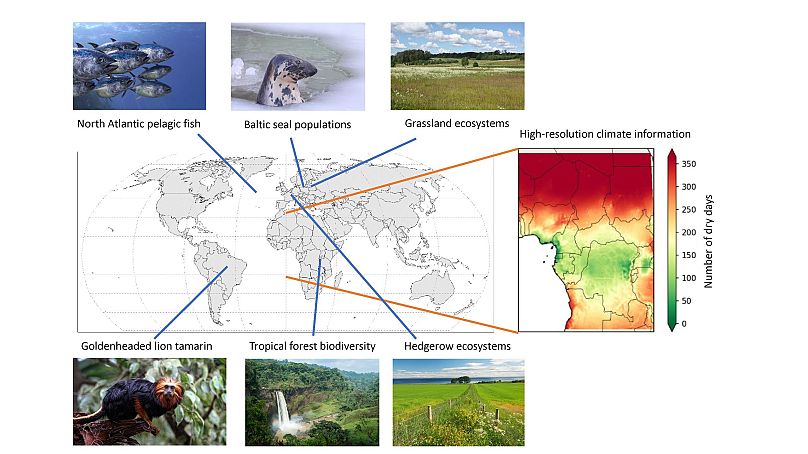

With the service going live at the end of 2020, C3S scientists have already tested the data for plants and animals species across the world. “We’ve been looking at how tropical forests in Central Africa will adapt to changing rainfall regimes, or at how shifts in sea ice concentration will influence seal conservation in the Baltic Sea,” says Dr. Almond. In Brazil, experts are looking at how climate conditions might affect the range of the golden-headed lion tamarin, an endangered monkey. “An analysis based on tailored climate indicators has shown that future climate conditions will be unfavorable for tamarins in the nature protection areas where they currently live,” explains Prof. de Ridder. “This knowledge, together with other types of information, is being used in making conservation plans for the species.”

Tracking how species that are regularly on the move will react to climate change is another testing mission. One app explores the connection between bird migration dates and climate variables. It does so across Europe for flagship species such as white storks, or black kites by combining data provided by citizen science projects with earth observation data from C3S. “Data gathered in initiatives such as eBird together with recently available high resolution satellite imagery offers a powerful and cost-effective tool for the long-term monitoring of migratory birds and other species,” says Juan Arevalo, managing director at Randbee Consultants, a company providing data analysis for environmental policy. “Detecting the impacts that climate change is having on bio-indicator species such as migratory birds allow us to better understand the effects on ecosystems and to make the most suitable management decisions to help their conservation,” explains Arevalo.

Climate change also interacts with other threats facing species, stresses Dr. Urban, making it critical to model how species might react to the combination of those threats. When it comes to making biodiversity predictions more accurate, Urban is hopeful, drawing a parallel to how far we’ve come in predicting climate. “The original models we had were quite poor, but step by step climate scientists collected the information, created a global monitoring system, figure out what mechanisms and processes they needed to include; we’ve seen dramatic increases of forecasting accuracy and in the ability to hindcast climate. We’re talking about the same thing in biology. Only that we are looking to make predictions for millions of species.” Choosing which species to make predictions for using platforms such as C3S’s comes with dilemmas. So far, the C3S biodiversity service has been used for species based on the biodiversity community agenda. Dr. Urban says that focusing on species that are expected to be endangered is critical for protecting them, while not losing sight of those species that might be at risk in the future. “Now that we understand better climate change, we need to understand what those impacts on biodiversity really are and find ways to mitigate them,” Dr. Urban says. “It really comes down to resources. We’re trying to focus the world’s attention that this is a really critical thing. It would be a real shame to lose many species to climate change, as they really determine our health, our economy, and even our culture.”