We meet a surfing scientist and toxic algae hunters to see how Sentinel-3 satellite data is used to study the coastline of the English Channel in this month's episode of Space.

Bob Brewin is pioneering a new technique in satellite oceanography - by going surfing.

The Plymouth Marine Laboratory scientist uses his board to take sea surface temperature measurements, and then use them to better interpret data from European satellite Sentinel-3.

He does so because there's a real need for those measurements: "In this near-shore region of the ocean there is a lack of observations, such that we don't really know well the accuracy or the precision of the satellite observations."

The lack of readings directly in the water complicates the job of understanding satellite measurements along the coastal zone.

Bob wants to fix that problem with a device called a SmartFin.

"This SmartFin is the same size and weight as a normal surfboard fin, but it contains a temperature sensor, a GPS device, an accelerometer for measuring motion, and it has Bluetooth capabilities to transfer the temperature and motion data from the fin onto your mobile phone," he says.

So, each time Bob surfs - which is at least once a week - the fin records the temperature. It's a new way of monitoring the coastline of the English Channel, a place which is important for many forms of life, and is sensitive to climate change.

"It’s a vitally important region of our seas," explains Bob. "It contains very high levels of marine biodiversity, marine productivity, it’s the spawning ground for many economically important species of fish. And it’s the foraging ground for marine vertebrates such as seabirds, kitty wakes and guillemots."

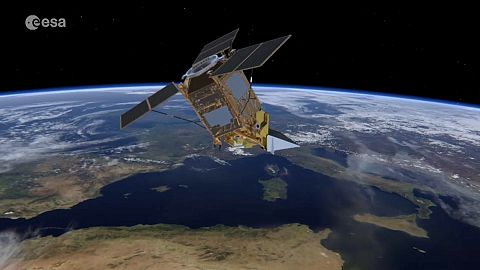

Sentinel-3B joins 3A on a polar orbit

Bob and his colleagues work with data from the Sentinel-3 satellite, part of the European Commission's Copernicus fleet of Earth observing spacecraft. This month the new Sentinel-3B satellite launches, joining the Sentinel-3A satellite, which launched in 2016.

For four months both satellites will fly just 30 seconds apart on their 800kilometre high polar orbit, effectively 'seeing' the same view of our planet at the same time. Later they will fly separately, providing daily coverage of the planet.

The pair will measure sea surface temperature and ocean surface colour, and are being flown in tandem at first to verify and cross-check their readings, as ESA Copernicus Space Segment Programme Manager Guido Livrini explains: "The reason why they fly in close formation at the beginning is we want to cross-calibrate the measurement that we obtain from the 3A which has already been validated, with the measurement that we will obtain from its twin, Sentinel-3B. Later on we will have a constellation in orbit of two satellites that will provide comparable data of equal quality but much more frequently than what one satellite alone could do."

Hunting for toxic algae off the coast of Normandy

Accuracy and frequency is exactly what interests scientists from French research organisation Ifremer studying algae, in particular harmful algae, in the waters of Normandy. We hopped aboard their high speed rigid inflatable boats on a their regular outing to take samples off the coast of Courseulles-sur-Mer.

Every two weeks they measure the temperature, salinity and oxygen level of the water, and combine it with Sentinel-3 data.

Scientist Tania Hernández Fariñas explains the goal: "Here we're measuring several abiotic parameters. These abiotic parameters will be used to relate with algal blooms, and the growth of the algae, and it's those algae that we try to observe from the satellite, which has much larger spatial and temporal coverage."

The crew are swiftly back on shore and into the lab to study what's in the seawater.

Tania explains the need for speed: "You have to be aware, these are biological communities, so the analysis has to be done as fast as possible. So once we've taken the samples at sea we come straight back to the laboratory to do the analysis"

Tania works in a new project called Sentinel-3 Eurohab to study harmful algal blooms, which are poisonous for fish and even humans. It means using space data and sea measurements together:

"The satellite captures a broad view of the production of phytoplankton. With the in situ measurements we'll be able to go further and explain which species were seen by the satellite and to identify the species which are toxic," she says.

The team has already spotted an important trend - the intensity of the phytoplankton blooms has dropped significantly in the past two decades in the English Channel. There is speculation that this is linked to changes in environmental regulations reducing the use of phosphates in household products and less fertilizer being sprayed on farmland.

Francis Gohin, who also works on the Eurohab project at Ifremer, told Euronews: "We have studied all the data on sea water colour coming from NASA and ESA over the past 20 years, in order to follow the evolution of the quantity of phytoplankton from day to day around the coastal waters of the English Channel and the Bay of Biscay. And what we have seen is a relative reduction in the quantity of phytoplankton, especially in the summertime."

Citizen scientists and Sentinel-3

Back at Plymouth Marine Laboratory and Bob Brewin explains how he would like to develop the SmartFin as a 'citizen science' project, deploying the technology around Europe and the rest of the world in order to help him with his ultimate goal of combining Sentinel-3 data and in situ readings to understand climate changes along coastal regions.

"The dream is to have surfers, and not only surfers actually, but also other water sports enthusiasts, canoists, standup paddleboarders, divers, who also regularly go in and out of the ocean for fun, equipped with these types of technology," he says.

"They can measure important components like temperature which we can use synergistically to really improve our satellite datasets."

The potential to realise that dream is there - In the UK it's estimated that 40 million coastal sea surface temperature measurements could be taken by surfers every year.