Did nationalism doom the ISS? Its demise is signaling a new era of space competition

The International Space Station is approaching the end of its lifetime. This is why we’re unlikely to see another similar project take its place.

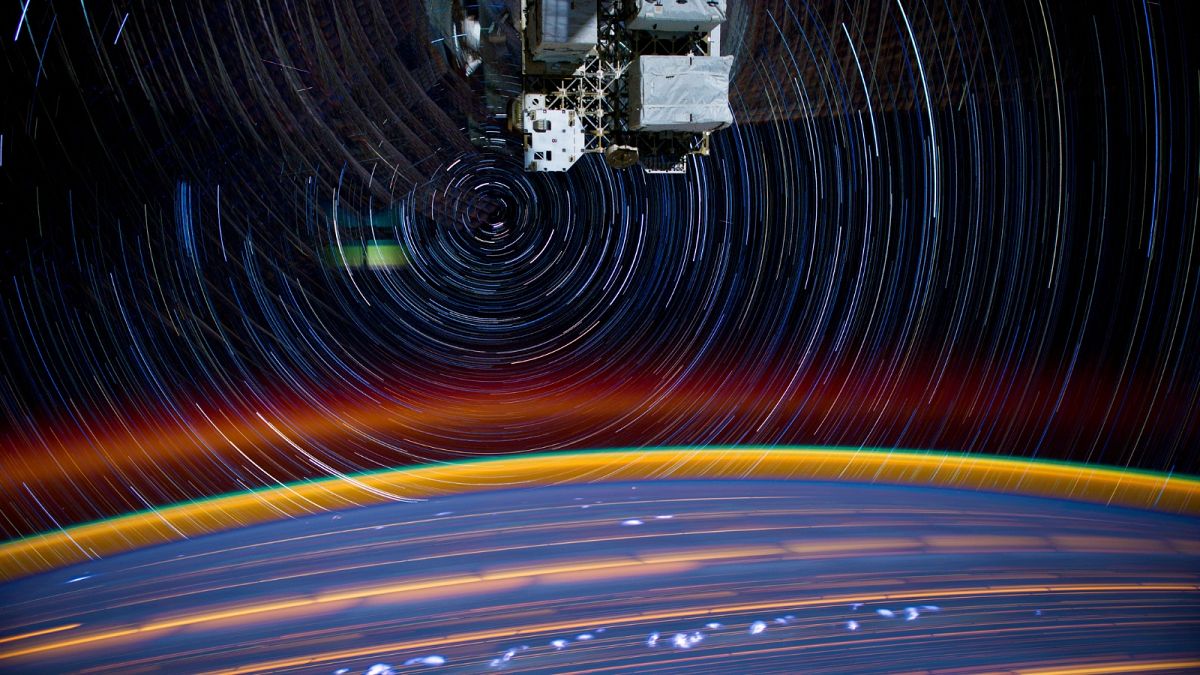

Orbiting the Earth since 1998, the International Space Station (ISS) is a multilateral project involving five space agencies from around the world.

It has conducted thousands of experiments and helped superpowers keep corridors of communication open, even when relations on Earth have been frosty.

However, it’s unclear if the ISS will even reach NASA’s proposed 2031 end-of-life date.

Key partners are threatening to pull out over rising tensions and costs at a time when the ISS is more needed than ever.

So, why won’t we see another internationally constructed space station on this scale, and what does the ISS’s demise tell us about rising conflict in space?

The origins of the ISS

The world’s first space station, Salyut 1, was launched by the Soviet Union in 1971. The US followed suit in 1973 with its manned Skylab.

However, decades of Cold War and space race antics ended with the 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union and in 1991 former rivals came together to work on the ISS.

Dr Mariel Borowitz, an expert in space policy issues and Associate Professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology, argues that building and deepening international relations was probably the most important goal of the ISS.

She says a driving reason for the ISS was "working with allies on a big, highly visible, scientifically and technically advanced project, but then also engaging with Russia specifically on this kind of peaceful cooperation".

Borowitz stresses that this international cooperation was also accompanied by scientific benefits and advances in technology and capabilities for human exploration in space.

The project also lowered the costs for participating nations by pooling their resources.

Dr Dimitrios Stroikos, Head of the LSE IDEAS Space Policy Project and Editor-in-Chief of Space Policy, highlights a further strategic reason for the inclusion of Russia in the ISS project.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, he believes it was a way for the Americans to keep Russian scientists and engineers engaged and prevent the sharing of sensitive technology with rival states.

Rising costs and different goals

Given its scientific benefits and boost to international cooperation; why are we talking about the end of the ISS?

One of the major reasons is rising costs and shifting strategic goals, which are very different now from when the ISS was first established.

The ISS costs NASA alone about €3.8 billion ($4 billion) a year to operate, with the European Space Agency (ESA) putting the price of developing and running the ISS over ten years at €100 billion.

Unfortunately for the countries participating in the programme, the station is ageing quickly, further driving up operating costs.

While the retirement date for the ISS has been extended previously, in recent years, the ISS has suffered from air leaks, software failures, and fire alarms being triggered.

The rising cost of maintaining the ISS comes as countries are turning their attention to new projects, such as NASA’s Artemis programme tasked with returning humans to the Moon or sending rockets to Mars.

The commercialisation of space and the increasing use of private companies by NASA has also made a new intergovernmental ISS unlikely.

Under its Commercial LEO Destinations project, NASA will commit almost €500 million to private companies developing private space stations.

A more weaponised and contested space

However, another reason for the demise of the ISS is that space is fundamentally more contested and is being increasingly weaponised by competing powers.

Rising tensions and geo-political struggles on Earth are also spilling over into space.

While the US is outsourcing its space station capabilities to private partners, rising powers are set on developing their own space stations.

China, which since 2011 has been shut out of projects involving NASA due to the Wolf Amendment, is constructing its own Tiangong space station. The station is planned to be finished by the end of this year.

Following Putin’s invasion of Ukraine and subsequent sanctions, Russia has also confirmed that it intends to leave the ISS programme by 2024 to pursue its own space station which it said would be open to cooperation with "friendly countries".

In September, Russia’s recently-appointed space chief, Yuri Borisov, branded the ISS as “dangerous” and unfit for purpose.

"Technically, the ISS has exceeded all its warranty periods," he said. "An avalanche-like process of equipment failure is beginning, cracks are appearing".

Chinese space efforts have also prompted other space powers, such as India, to accelerate their own plans for national space stations.

Dr Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan, Director of the CSST and former Assistant Director of India’s Security Council Secretariat, says there is no doubt that space is becoming more contested.

However, she also says that this increased contention has led to new partnerships and developments that would have been hard to predict a decade ago.

"This competition is also spurring a certain amount of cooperation, which otherwise may not have been seen, for instance, the quad countries [America, Australia, India, and Japan] talking about space competition," Rajagopalan said.

An example is India’s increased cooperation with Japan, the US, and Australia and its leading role in talking about norms, rules, and regulations in space.

"We may be witnessing the emergence of two camps, one US-led and the other led by China and Russia, sort of spheres of influence in space characterised by competition," Stroikos added.

He adds that unlike during the Cold War, today, great space powers aren’t talking to each other and that that’s quite problematic but doesn’t have to mean conflict in space is inevitable.

Bigger issues to resolve in space

While the demise of the ISS is one of the most visible signs that we’re entering a different era of space politics, Stroikos argues that we shouldn’t let it distract us from bigger issues.

"My main concern is how higher tensions will further increase mistrust among great space powers, at a time when cooperation is urgently needed in order to tackle global space challenges, such as space debris, and establishing norms of responsible behaviour," he said.

It remains to be seen whether attempts to resolve tensions and space policy issues will succeed or whether, like the ISS, they’ll come crashing back down to Earth.