UN Special Rapporteur Oliver De Schutter explains why he thinks the EU needs to quit an agreement that protects the interests of the fossil fuel industry.

Olivier De Schutter is the UN Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights.

As global leaders continue critical climate talks at the COP27 conference, the EU is deliberating whether it wants to reform or quit an agreement that protects the interests of the fossil fuel industry.

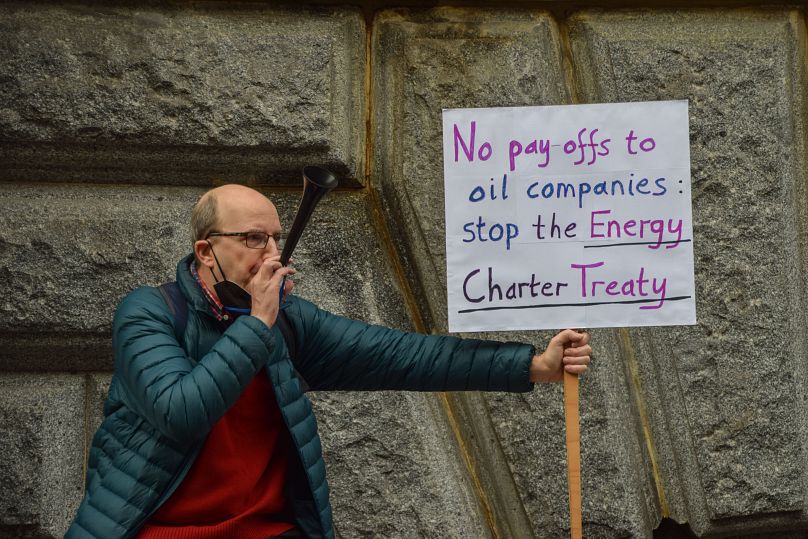

The Energy Charter Treaty (ECT) is an international agreement signed in the 1990s that allows energy investors to sue governments for policy changes - including for taking vital climate action.

It is a deterrent to states introducing measures to curb greenhouse gases. The fear of facing massive pay-outs, such as the €240m award Italy was forced to pay British oil firm Rockhopper, can stunt government ambition.

The EU has already made a flawed attempt to ‘modernise’ the treaty to address its climate problems. But the outcomes of the reform fail to fix its conflict with the bloc’s climate commitments and incompatibility with EU law.

It's therefore absolutely right and applaudable that major EU countries, including Germany, France, Spain, Poland, Slovenia, and the Netherlands recently announced their intention to withdraw from the ECT.

The European Commission, however, is dead-set on remaining a member. It is pushing national governments to greenlight the amendments to the ECT in a crucial vote this week that is set to define the Union’s climate leadership.

If member state leaders are serious about tackling the climate crisis, they must block it. The new ECT fails to align with EU and international climate objectives leaving countries vulnerable to legal action for adopting vital climate policy measures.

It also creates new risks for member states navigating their energy transition.

Even if reformed, the ECT will protect investments in fossil fuels for at least another decade in the EU and open new dangers with protections expanded to other controversial energy sources, such as biomass.

Whatever progress is made at the climate talks in Egypt, the ECT will continue to block climate action in the critical years to come, and make the energy transition more expensive.

Approving the reforms will create new legal problems

For the countries that have already moved to exit the treaty, they must follow through on their decision to leave and vote down the new agreement. Supporting the amendments risks creating an uncertain, chaotic, and problematic legal environment.

The upcoming Council’s vote, delayed several times already, will form the common position of the EU to be taken to a meeting in Mongolia on 22 November, where all 52 signatories of the ECT will decide to adopt or reject the reformed agreement.

If the countries leaving the treaty - together with Italy, which left in 2016 - support the amendments, then they will be sending an unhelpful contradictory signal on the international stage.

Worse still, it is incoherent for the EU to remain a party in its own right to a treaty that several of the largest EU countries have found to be an obstacle to climate action.

The ECT is a mixed agreement that touches on the competence of member states. That means it should require ratification – all EU member states should have to approve it to enter it into force in the bloc.

Securing the consent of all EU governments, even those that want to leave or have left means ratification of the reformed treaty is bound to fail. Attempting it could waste years, with severe reputational damages to external relations.

It’s nonsensical that the “exiters” and even the EU would commit internationally to something they already know they can’t deliver.

Then there is the issue of the duty of loyalty of the member states towards the EU.

Adopting a common position “to raise no objection” to the adoption of modernisation would bind member states' hands. It would also postpone their ambition to individually withdraw from the treaty until ratification - which they would be obliged to seek under this duty – eventually fails at a later stage.

At least 80 cases for compensation have been brought under the treaty so far

Ultimately, the revolt against the ECT has been fuelled by the rise in dispute settlement claims between investors and states. They are decided by panels of corporate representatives in secretive tribunals and can result in multi-billion euro awards.

At least 80 cases have been brought under the treaty seeking compensation for environmental measures in its lifetime.

If the Commission was to attempt to bypass national parliaments on the ECT reforms, it would have enormous implications for the democratic legitimacy of EU trade decision-making. This concerns taxpayers' money and interference with national judiciary, and therefore national parliaments must have a say on these reforms.

It’s unclear what the consequences of these claims would be if member states had one foot in and one foot out of the agreement. There is too much uncertainty to blindly greenlight the reforms without clarity on the implications for member states who want to individually withdraw.

Should the EU withdraw from the Energy Charter Treaty?

Rejecting the modernisation would put the Commission under pressure to propose a withdrawal by the EU.

The right way forward is clear: a full-EU withdrawal is the cleanest way to release governments from the ECT’s shackles and make progress on their climate commitments.

Arguments against this approach claim that due to a sunset clause, which binds ECT members to the conditions of the treaty for 20 years after they leave, the reform is still favourable.

But there are solutions, known as an inter-se agreement, that would neutralise the effects of the clause and allow the EU and potentially other ECT signatories to end treaty protection earlier.

Member states that want out must use their voting power now to block the reforms and kick-start that process.

The time for the EU to finally abandon the outdated, damaging agreement is now. COP27 is a good reminder of the need to walk the walk rather than just talk the talk.