As conversations about decolonisation increase, more museums are considering returning their looted African heritage, but is this the right approach?

Museums around the world are returning or considering the return of heritage artefacts that originated in colonised lands.

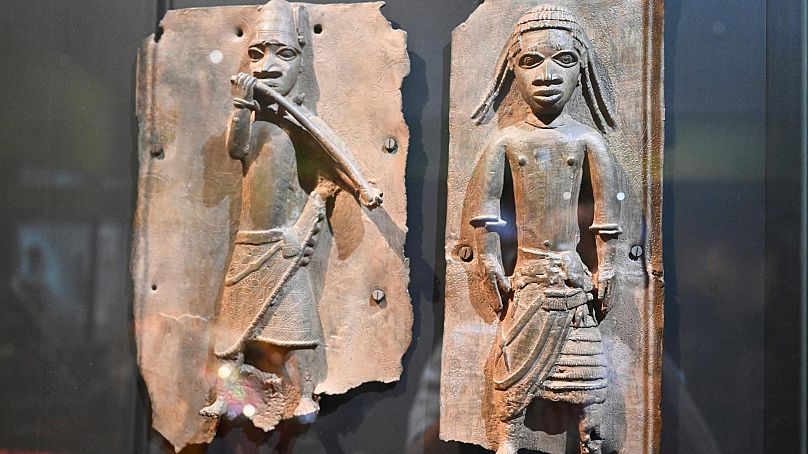

Paris has just returned 26 royal antiquities, looted by French soldiers in the 19th century to Benin, while Sudanese museums are requesting their artefacts back too. And perhaps most famously, the British Museum is finally opening up a dialogue about returning the Parthenon Marbles.

But where has this trend come from in recent years?

France's big promises

While the conversation around returning human remains held in museums has been around for a long time, Paul Basu, Hertz Professor of Global Heritage at the University of Bonn says, the discussion about returning African items is much more recent.

Much of the political conversation comes from France. Emmanuel Macron’s visit to West Africa in 2017 saw him make a landmark speech promising the return of many heritage objects.

“African heritage cannot solely exist in private collections and European museums,” Macron said in a speech at the University of Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso.

“African heritage must be showcased in Paris but also in Dakar, Lagos and Cotonou; this will be one of my priorities. Within five years I want the conditions to exist for temporary or permanent returns of African heritage to Africa,” he said.

“One can argue about the political or diplomatic objectives of what he was saying there. But it was a very public statement,” Basu says.

After that, Macron commissioned a report by Senegalese academic and writer Felwine Sarr and French art historian Bénédicte Savoy to assess the African cultural heritage in France and the methods of restitution.

The report influenced other European countries and reinvigorated a movement to return the Benin Bronzes which has since seen France, Germany and the Netherlands all participate.

In the public sphere, the necessity for decolonising museum collections has grown through the rise of Black Lives Matter. Basu also credits the Rhodes Must Fall movement, a campaign to remove the name of slave owner Cecil Rhodes, from university buildings in South Africa and the UK.

“One of the key points is the shift in language from the idea of the post-colonial to the decolonial,” Basu says, an idea that has been highlighted in the public consciousness by the Black Lives Matter movement.

It's not just about returning the items

We can’t just return these items, says Dr. Evangelos Kyriakidis, director of the Heritage Management Organisation.

For a long time, one of the ways museums with colonial artefacts have justified holding onto the objects is because museums in the origin countries do not have the facilities to look after them.

“Say we Europeans give them back their stuff. And then 10 years later, we go back and point the finger at them saying, ‘Look, we told you, you didn't have good enough museums for this. We should have them back and you're not going to get anything else…this is a dishonest trap’” Kyriakidis says.

While this is a legitimate worry for caretakers of heritage, instead of curators burying their heads in the sand, a lack of facilities and management capacity in origin countries should present an opportunity for a greater offer, Kyriakidis suggests.

As many of the origin countries have spent a long time under colonisation or occupation, they have often been treated as second-class countries within an empire. This treatment is at the root of why their facilities today may not be up to the standard expected of a Western European museum.

“Your responsibility towards heritage and towards humanity says that you must return these artefacts,” he says.

“You must make sure that whoever receives them can look after them. So you must put a budget aside. And you must use your human resources to be able to train locals and to create the right conditions for these items to be exhibited properly, to be stored properly and to be conserved properly in perpetuity,” he continues.

As institutions like the British Museum claim they’re looking after pieces as a service for humanity, they also neglect their duty to the communities where these pieces originate.

If countries want to truly end the cycle of colonialism and imperialism, then it is crucial that collaboration with source countries is prioritised in the return of stolen or appropriated goods, Kyriakidis emphasises.

The current approach, as seen with the return of the Benin Bronzes by France, the Netherlands and Germany, is that the items are given back and presented alongside a plaque that commemorates the pledge made by the respective government.

“But imagine how different this would have been if the repatriated artefacts came back to a museum that was built with the aid of the ex-colonial or imperial country. That you could be in a whole museum that was the gift of the people of that country to the people of the origin country, like Benin,” Kyriakidis suggests.

The future of the museum

Basu suggests that a truly decolonial approach to museums could see the disposal of the museum building as a concept entirely.

“It's a very static idea of a museum,” he says, “personally, I'm much more excited by the possibilities of a trans location of the idea of the museum.”

Disconnecting the concept of a museum as a building with storage and instead replacing it with the concept of shared knowledge and stories would be Basu’s preference.

“This is about recognising that as a consequence of the same colonialism that we're talking about which has dominated the political world but also meant intellectually and epistemologically in terms of what we know, how we know, and what being in the world means,” Basu says.

A more holistic approach to bringing items back to Africa is important because in many cases, the cultures in question are still extant.

“The debate has also been dominated by what you might call exceptional objects,” Basu explains. As looted objects like the Benin Bronzes and the Parthenon Marbles dominate conversation, there is also an important dialogue to be had about the everyday African heritage objects on display in European museums.

For his work with the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Basu worked with 20th century surveys of Sierra Leone. The surveys included photographs and audio recordings, which Basu has been able to retrace back to their communities.

“It's very interesting what people really care about and the connections people make, particularly with photographs of ancestors or the voices of ancestors,” Basu remarked.

“For a lot of the items that are in private collections, or in museums around the world, from Africa, they actually come from local communities that are still around,” Kyriakidis says.

Which also means, from a heritage perspective, not allowing those communities to have access to the items, means a lack of ability to meaningfully learn about the items from those same communities.

Africa as a heritage hub

Kyriakidis’ work at The Heritage Organisation heavily focuses on projects within Africa to grow skills for managing heritage. They work alongside the African Union, the Economic Commission for Africa, the European Union and other stakeholders.

“We think that actually Africa has a fantastic opportunity to not only catch up, but overtake a lot of the currently famous heritage countries,” Kyriakidis says.

“We must stop saying that Africa is not a continent important for heritage, because Africa is the most important continent for heritage.

"It has more heritage alive with greater diversity, more rich heritage, and it's just a continent with not as many monuments as Europe or Asia or Mesoamerica. But that doesn't mean it's poorer, it's probably richer.”