Sweden has been left shaken by grenade attacks in recent years. Euronews explains why the country, known for its crime safety, has a grenade problem.

By Karis Hustad for Euronews

On a Sunday this January, Daniel Cuevas Zuniga, a 63-year-old Chilean living in Sweden, was cycling home in Vårby Gård, a suburb of Stockholm, with his wife. He saw an object on the bike path and reached down to pick it up. It was a hand grenade.

It exploded, and Zuniga died from his injuries. The blast was so strong it threw his wife off her bicycle in front of him.

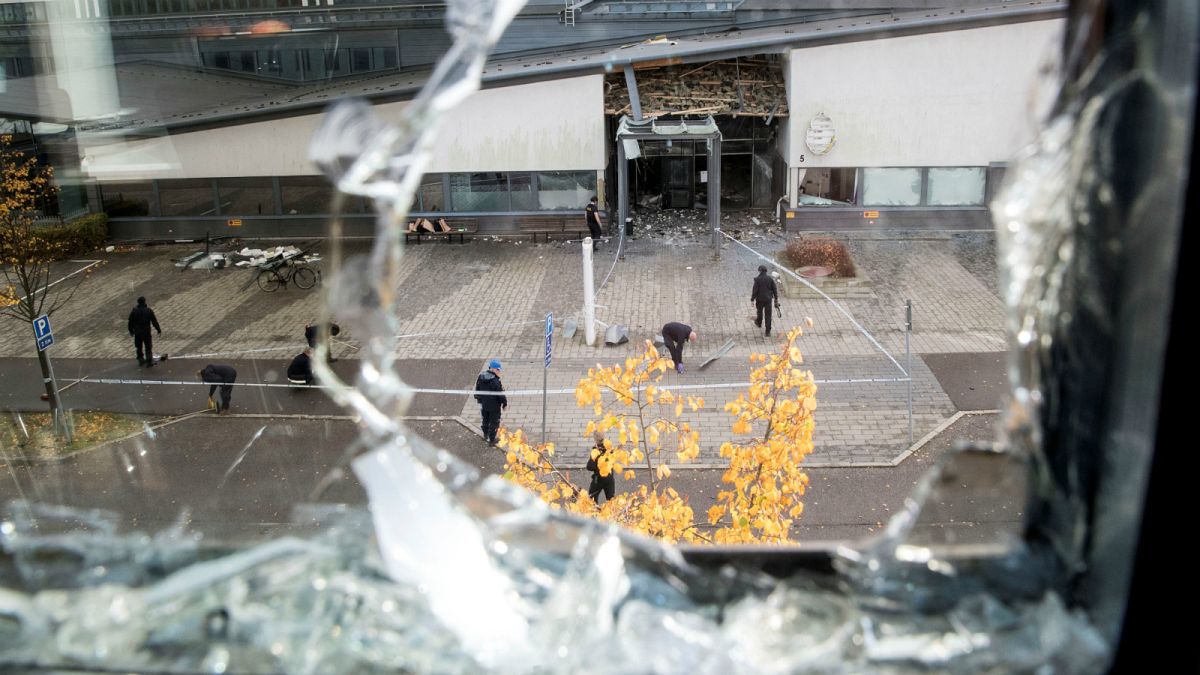

It was one of the latest violent incidents in a series of hand grenade explosions and attacks that have shocked Sweden in recent years.

In 2015 police seized 45 hand grenades, and 10 were detonated. In 2016, police seized 55 hand grenades, and 35 were detonated. In 2017 the numbers dropped slightly: 43 were seized and 21 were detonated. So far in 2018, there have been three grenades seized and two detonated. The explosions have been spread across the country.

While the numbers have fluctuated over the last few years, cases seem to be spiking. In ongoing research, an inter-institutional team of criminologists and researchers have counted 78 cases of hand grenade explosions since 2010, with half of those cases occurring in 2016.

Zuniga’s death was an anomaly. He was one of just two people — both bystanders — who have died in grenade attacks since 2015. The other was an 8-year-old boy from the UK who was killed after a grenade was thrown into the apartment where he was staying in Gothenburg. Police believe the attack on the boy was connected to a gang feud.

Why grenades?

Crime in Sweden is still relatively low by international comparisons. But the nature of hand grenades —weapons usually used for war — as well as the context of an uptick in violent incidents and lack of research on the problem has the generally peaceful country on edge.

“Overall, violent crimes have gone down big time in the last 40 years, although the ones that do occur are a lot more violent, a lot more gun-related than they have been before,” said Joakim Palmkvist, a crime journalist at Sydsvenskan and author based in Malmö, to Euronews.

The hand grenade attacks are connected to gangs and organised crime, but don’t seem to be perpetuated by one particular group, said Palmkvist. One theme that could tie the attacks together, he said, is intimidation. The most recent attack in March, for example, was carried out by two gang members who threw a grenade at the house of a banker who was investigating fraud related to organised crime.

Hand grenades lend themselves to this sort of criminal work, said Palmkvist. Using a gun to, say, shoot someone in the leg in order to get a debt paid is “full of troubles,” he said, including DNA evidence, traceable bullets and harsh possession sentences. Hand grenades are less cumbersome and less likely to leave evidence.

“Being a criminal you need tools to do your dirty work, and [grenades] are a lot smarter to use in that sense than guns,” said Palmkvist.

Part of the problem may have stemmed from how hand grenades has been historically treated in Swedish law. Previously hand grenades were governed as “flammable and explosive materials,” rather than weapons, and the minimum sentence for possession was just six months in prison, reported The Local.

That law was amended in January 2018, in response to the attacks. Now the minimum sentence for aggravated breaches is two years in prison. More serious offenses carry a minimum sentence of four years.

“That’s giving the police the ability to actually arrest people and incarcerate people for a longer time,” said Amir Rostami, a researcher at Stockholm University, who is part of the team researching the use of hand grenades. “Criminals carrying weapons now have to think about the consequence a little bit more.”

From the Balkans to Swedish homes

The most common hand grenade used in Sweden is the M75, which originates in the Balkans and is brought into Sweden by car, truck and bus. There is an excess of the weapons in the Balkans, left over from the Bosnian War, and police believe the hand grenades are thrown in for free with orders of AK-47s. Palmkvist noted that previous connections in Sweden’s gangs could be drawing a line from Eastern Europe to Sweden.

“There is a wide, deep and heavy road for contraband being transported to the Nordic countries from the Balkans,” said Palmkvist.

A smuggling law reform passed in November could help. Previously explosive devices did not have to be reported to customs authorities when entering the country. Now the devices must be reported, and failure to report is considered smuggling.

That said, these laws won’t impact the grenades that have already been brought into the country and remain unused. Police have suggested a grenade amnesty for October 2018 to January 2019, which would allow people to turn in their weapons. A similar one for illegal firearms is underway through April, and has seen modest success.

Amnesty divide

Palmkvist and Rostami were both skeptical that the amnesty would work with gangs. Instead, they said there needs to be more focus on the context that leads to gang violence.

“To stop hand grenades, we need to stop people from trying to get them,” said Palmkvist.

Sweden Democrats, a right-wing anti-immigrant party that has been steadily gaining ground in the country, blame Sweden’s openness to immigrants, asylum-seekers and refugees for fuelling gang violence.

While a 2012 study led by Rostami found that 76% of gang members are either first- or second-generation immigrants, the ethnic makeup of gangs is heterogenous (hailing from 35 different countries) and 42% of the gang members are born in Sweden.

Government studies found that the majority of people suspected of crime in the country are born in Sweden to two Swedish-born parents. And while people with foreign backgrounds are 2.5 times more likely to be suspected of crimes than ethnic Swedes, the vast majority of people with foreign backgrounds are not suspected of a crime.

Researchers at Stockholm University found that socioeconomic conditions seem to be what separates criminal activity between immigrants and others in the population. Rostami pointed out that Sweden has under-served its socially vulnerable areas with higher numbers of immigrants and low levels of education and income, which can increase risk of crime. Plus, strong labor unions keep entry-level wages high, which de-incentivises the hiring of employees who lack education or Swedish language skills. About 16.6% of foreign-born men are unemployed according to OECD statistics, one of the highest levels in the EU.

Joining a gang could be partially rooted in seeking a “new brotherhood” in the face of these economic and social challenges, Rostami explained to Euronews.

“Our models and our ethos are not reaching those groups and areas that need the most help,” he said.

Rostami also pointed that a mass reorganisation of the Swedish police in 2015 shifted administration from 21 different regional organisations to one single agency, which may have disrupted connections to local intelligence. The Swedish Police Union said the police authority was “in crisis” in 2016 in response to a government issued report that found local police work hadn’t been sufficiently prioritized as the reorganization progressed. Earlier this month, Gunnar Appelgren, a police superintendent and specialist in gang violence, told the New York Times “We’ve lost the trust of those in communities.” Appelgren, nor the Swedish Police Authority, responded to an interview request.

To address these concerns, the government said it would bump up the allocated budget for the Swedish police to 2 billion kronor (€194 million) by 2020.

Hand grenades are just one issue in the context of violence that has surprised Sweden. There has also been a slight uptick in firearm violence, although the overall levels have trended downward in the last 25 years. There have been non-hand grenade explosions, indicating that other bombs may also be a growing concern.

With that in mind, Rostami said Sweden’s sudden spike in hand grenades will need a broad solution.

“You cannot prevent hand grenades if you are not preventing gang violence,” said Rostami. “You can’t only target hand grenades.”