Scientists found the bacteria causing leprosy can make livers regrow healthily in animals, holding promise for future regenerative treatments.

Leprosy is one of the world’s oldest and most unpleasant diseases, but the bacteria behind it may also have the unexpected ability to grow and regenerate a vital organ.

Scientists have found that these bacteria can reprogramme cells inside animals to expand the size of their liver without causing damage - and instead giving them a “rejuvenated” state.

Mycobacterium leprae can infect the nerves, skin, eyes and lining of the nose, causing the disfiguring sores, lumps and bumps that characterise leprosy.

This bacteria can “hijack” cells to spread through its host by giving it more tissue to infect, Professor Anura Rambukkana, of the University of Edinburgh’s Centre for Regenerative Medicine, said.

“This bacteria cannot grow in a lab dish like E.coli or others. It has real limitations in that respect. Of course, limitation breeds innovation,” he told Euronews Next.

Rambukkana and his colleagues say uncovering how these bacteria can regenerate tissue could lead to new life-saving and anti-ageing therapies, and avoid the need for liver transplants.

Leprosy bacteria can ‘reprogramme’ cells

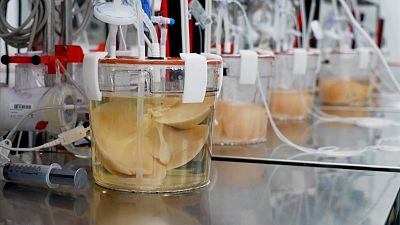

Working with the US Department of Health and Human Services in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, the team infected 57 armadillos – a natural host of leprosy bacteria – with the parasite and compared their livers with those of uninfected or infection-resistant armadillos.

They found that the infected animals developed enlarged yet healthy livers with the same vital components - such as blood vessels, bile ducts and functional units known as lobules - as the uninfected and resistant armadillos.

Rambukkana said a liver pathology expert on the team who compared the liver tissues was “amazed at how normal the livers were” and could not tell which ones had been infected and which ones were immune. “It was that good”.

Livers of the infected armadillos also contained gene expression patterns – the blueprint for building a cell – similar to those in younger animals and human foetal livers.

Scientists think this is because the bacteria “reprogrammed” the liver cells, returning them to the earlier stage of progenitor cells, similar to stem cells. These then differentiated into new liver cells and grew new liver tissues.

Repairing damaged livers - and more

The team hope their findings, published in the journal Cell Reports Medicine, hold the key to advances in regenerative treatments that could repair damaged livers in humans and even reverse some of the damage caused by ageing in other parts of the body.

Liver diseases currently result in two million deaths a year worldwide. Liver transplantation is currently the only curative option for people with end-stage liver failure.

In no way is the team thinking of infecting people with leprosy bacteria; it’s simply observing how they behave in the body to uncover pathways that could in future be induced with a drug, Rambukkana explained.

“They have trained for millions of years in their natural host to do this job very precisely,” he added.

Dr Darius Widera, of the University of Reading, who was not involved in the study, welcomed the findings.

"Overall, the results could pave the way for new therapeutic approaches to the treatment of liver diseases such as cirrhosis,” he said.

"However, as the research has been done using armadillos as model animals, it is unclear if and how these promising results can translate to the biology of the human liver”.

‘Beauty out of the beast’

To take this research further, Rambukkana and his colleagues are now studying leprosy patients in endemic countries such as the Philippines, India and Ethiopia, to see if the regenerative phenomenon observed in armadillos also occurs in humans.

This unconventional research has an interesting philosophical dimension, he said.

“We can learn rich biology from poor diseases which are neglected, and translate [the findings] to rich people's diseases,” he told Euronews Next, adding that the focus of this ongoing clinical research was on finding clues to regenerate the skin.

In other words: A disease that has disfigured patients for centuries, causing them to be shunned, could now potentially hold secrets for anti-ageing treatments in developed countries.

“We are trying to make the beauty out of the beast here,” Rambukkana said.