Miodrag Belodedici was Eastern European football's lucky charm, winning two Champions League titles in the 1980s. He also witnessed the fall of Ceaușescu and the bloody breakup of Yugoslavia.

Only two Eastern European football clubs have won the Champions League — known as the European Cup until 1992 — over its 66-year-long history.

One man played for both teams, Romania’s Steaua Bucharest and former Yugoslavia’s Red Star Belgrade.

His name is Miodrag Belodedici.

A lanky yet elegant defender with a thick tangle of jet black hair, Belodedici stood out in the 1980s as one of the most reliable sweepers on the continent.

A former Romanian national superstar in his own right, his calm demeanour echoed the composure of a skilled player that stopped world-class attackers from the likes of Barcelona and Bayern Munich dead in their tracks.

“Whenever I thought about my career, I always saw it as somehow my destiny, growing up as a fan of both clubs,” Belodedici told Euronews. “The two stars, right? Steaua also means ‘star.’”

Belodedici, who reached the top of European football and lifted the coveted trophy first with Steaua in 1986 and then Red Star in 1991, grew up in the ethnically mixed area of Romanian Banat on the river Danube.

He was born in one of the only two Serb-majority towns in Romania, Sokolovac or Socol. The Serb minority in Romania, which has historically inhabited the lands along the Danube and Nera rivers, includes Dositej Obradović, a central figure in the reformation of the Serbian language, and Romanian poet Alexandru Macedonski — the first poet to use free verse in Europe — to name a few.

Since Serbian was his mother tongue, Belodedici learned Romanian only in primary school and grew up watching Yugoslav TV. That is when he fell in love with football.

“In my village next to the border, we watched Yugoslav TV more because the reception for Romanian channels was very bad — so we watched Yugoslav sports and I became a Red Star fan. But I also liked Steaua.”

Romania was at the time considered to be a Soviet satellite state well behind the Iron Curtain, ruled by the communist regime of Nicolae Ceaușescu.

Ceaușescu, who came to power in 1965, was known for his cult of personality, most noticeable in the self-assigned titles, like "Geniul din Carpați”, or “The Genius of the Carpathians.”

Originally a compromise candidate, he managed to distance himself from Moscow over the years and became what some considered to be a reformist within the Eastern Bloc due to his relative openness towards the West.

However, his open admiration for the likes of China’s Mao Zedong and North Korea’s Kim Il-sung saw him turn Romania into a totalitarian surveillance state.

Ceaușescu’s personal whims often dictated his policies. A sports fan himself, he would ban or promote sports on a whim, prioritising those he had a personal liking for. During his rule, badminton and baseball were prohibited by decree — but football and gymnastics saw significant investments.

This meant funding for youth setups even in minor clubs was common, and scouts looked for prospective players in every town and village throughout the country. Recognised for his talent, Belodedici moved from Socol to the nearby town of Moldova Nouă on a football scholarship at the age of 14.

“Playing football was much more accessible, much better than today,” he said, remembering his times as a youth footballer.

“The Communist Party invested a lot in sports and there were more clubs, not just in football — handball or gymnastics, too. You could choose where to go and sign up to play football, there were so many clubs to choose from.”

As an army club, Steaua had the privilege to gather all youth players from the country soon to turn 18 and have their pick of the best and most talented.

Belodedici auditioned and got selected in 1982, supposedly after being hand-picked by the president of the club, Ion Alecsandrescu, who was on the search for a quality centre-back. He became a first-team regular by 1984, at the age of 20.

But the competition at the army-run clubs was fierce because of the privileges that came with the job, says Belodedici.

“Everyone wanted to play for Steaua or Dinamo Bucharest because that meant they would be relieved of military duty.”

The players’ contracts at Steaua were standardised according to rank, and everyone had one — even the players.

“When I first arrived at Steaua, I was given the rank of a private, the lowest rank. My last rank before leaving was lieutenant. But that only meant something in terms of your pay grade. I didn’t wear a uniform — I didn’t even have one,” he said.

When asked about his achievements with Steaua, including five domestic championships, four cups, and most important of all, the 1986 European Cup medal he won in Sevilla against Barcelona on penalties, Belodedici becomes noticeably humble.

“We played in Europe each year and we fought. So we reached the finals in 1986 and won the cup,” he said.

Minority athletes in communist states

But things were never good for Romania’s minorities, comprising a total of 12 per cent of the country’s population at the end of World War II.

Under communism, they faced constant threats of deportation or resettlement, such as the Soviet-ordered expulsion of ethnic Germans in 1945.

The 1951-1956 Bărăgan deportations saw minorities, including Serbs from Banat, deported from Romania as "elements who present a danger" to the Romanian regime.

The deportations were made worse after socialist Yugoslavia cut its ties with Moscow in 1948 and the two countries became separated by the Iron Curtain.

Although Ceaușescu disengaged from policies of resettlement and brokered a shaky yet permanent end to political hostilities with the likes of Yugoslavia, he was both suspicious of perceived outsiders and wary of the potential territorial pretensions of neighbouring countries like Hungary.

In response, he declared Romania a “unified country” and adopted the goal of "national homogenisation" in an attempt to further control all of the distinct ethnic groups, such as Hungarians or Ukrainians, disenfranchising them in the process.

Belodedici was lucky, however. After facing repeat rejections for his request to be allowed to move to Yugoslavia, he finally left using the fact that his family was issued a special pass given to those living in close proximity to the border.

“I actually asked to leave Romania much earlier. After a couple of years at Steaua, I asked for a passport to go visit my family [in Yugoslavia] together with my mother. But they didn’t want to issue it,” he recollected.

“The system was such — they told me, ‘there’s no one who can issue you a passport because none of the players has one.’”

In addition to yearning for a change of scenery, he was also getting increasingly tired of the constant paranoia and surveillance.

“Once I went to the bank to get some cash and the club brought me in for questioning: whether everything was okay, why I took out more money than usual, whether I had some kind of problems, those kinds of things. So I got angry and left.“ Belodedici remembers.

“We had special passes issued to minorities living in border areas that would allow you to enter Yugoslavia up to a certain number of kilometres.“

“Growing up in my village, I saw this happen all the time. Half of the village defected abroad. First, they’d go to Yugoslavia and stay there for a little while, and then they’d apply for asylum so they’d go to the US or Australia, Switzerland, Sweden.”

In 1988, he packed his belongings and went beyond those several kilometres, all the way to Belgrade. He was dead-set on continuing his career there.

After Belodedici left, although still an Eastern European behemoth, Steaua lost its second and last Champions Cup final to AC Milan by a whopping four-goal margin.

In Yugoslavia, he carried on as a nobody at first. After spending some time with his family, he decided it was time to go knock on some doors and start with his favourite club, Red Star.

“I went to the stadium to speak to [the technical director at the time] Dragan Džajić and to tell him about my situation. I asked him whether he’d take me in and let me play for them. I told him who I was, and he said he had heard of me and took me in,” Belodedici said.

“But he also told me that I’ll have problems because they didn’t know what the sanctions might be, because I switched clubs without permission.”

Although not registered as a professional player — Steaua’s players were technically enlisted officers — he ended up being suspended for ten months after the club’s consultations with UEFA.

“I knew it would happen. So I went and trained with them, I played friendlies in Serbia with the reserve team, and I prepared during that time.”

From one trouble to another

At the same time, in his native Romania, the people disposed of Ceaușescu in less than two weeks in late 1989.

It was minority communities in Romania that set off the first sparks of the revolution. In Timișoara, the local Hungarian community insisted on organising a vigil on December 15 in an attempt to prevent the communist government from deporting a local Reformed Hungarian Church pastor.

Soon enough, other groups like students joined in what became full-blown protests, channelling a general anti-government sentiment brewing in the country, further fomented by the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Ceaușescu responded with a brutal show of force, having police, military forces and his secret police Securitate open fire on the protesters on December 17.

Reports from the protests claimed that Timișoara hospitals were overflowing with injured protesters, while the numbers of those killed were estimated from several hundred to 4,500, as reported by Yugoslav news agency Tanjug.

Within days, the number of protesters went from thousands to 100,000 în Timișoara alone.

The protests turned into a revolution almost overnight. By Christmas Day, Ceaușescu and his wife Elena — who served as deputy prime minister at the time — previously caught hiding at an agricultural centre near Târgoviște were executed by a firing squad after a brief court-martial.

But Belodedici found himself in the midst of another drama, with the bloody dissolution of Yugoslavia becoming imminent with each passing day.

“When I first arrived, the political situation in Yugoslavia was still not very complicated,” he recalled.

“There were rumours, though. One year later, things got worse.”

The increased violent crackdowns of the then-socialist republic of Serbia and its leader Slobodan Milošević against ethnic Albanians in Kosovo paved the way for a rise in nationalist sentiments across the country, in Serbia and Croatia in particular.

Once he was cleared to play in the spring of 1990, it took him a year to win the Champions League once more, again on penalties against Olympique Marseille in Bari.

But the celebrations over a Yugoslav club’s first and last top European title were bittersweet and overshadowed by events back home.

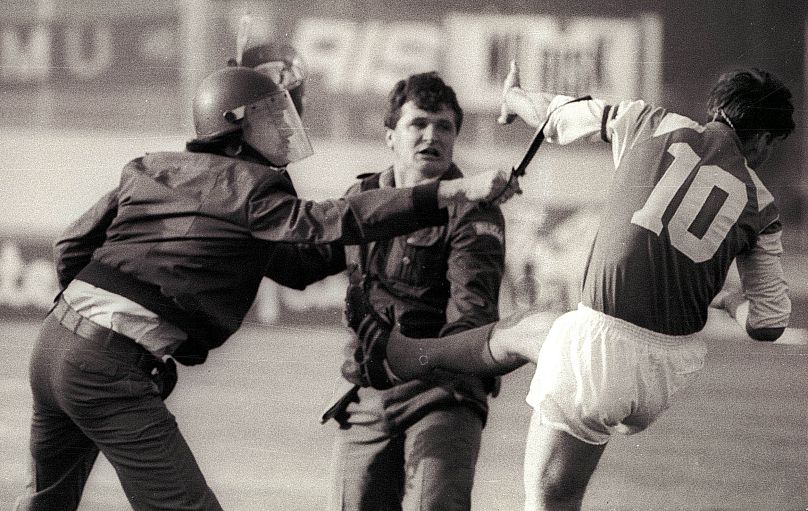

A match between Red Star and its rivals Dinamo Zagreb in May of the same year was cut short by an eruption of violence between the fans, spurred by nationalist sentiments, and for many still marks the beginning of the end.

Belodedici, who was in the Red Star’s starting eleven, was dumbfounded by the scenes at the Maksimir stadium.

“We went to Zagreb to play against Dinamo — you know the game when the hooligans tore down the fence and we had to flee across the pitch.”

“I had no idea what was happening. In Romania, Yugoslavia was Yugoslavia — the entire country was the same to us. I didn’t know about the problems they had.

“But to be honest, I got scared,” Belodedici said. “I thought, ‘I came to Red Star to play football and now I have to deal with this.’”

In 1991, almost all of the six Yugoslav republics — Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Macedonia — had already left the union or were well on their way to do so in response to an attempt by Serbia to dominate the federation.

Milošević, who positioned himself as the defender of Yugoslav unity as a foil for keeping all ethnic Serbs in one country, went on a series of military campaigns with the Serb-dominated Yugoslav National Army against all but Macedonia, with Bosnia bearing the brunt of the conflict as the most-ethnically-mixed state.

By the summer of 1992, when the war in Bosnia came into full swing and sanctions doled out by the international community against what was left of Yugoslavia prevented clubs from playing in any international competition, Belodedici got a transfer to Valencia.

The Yugoslav dream was over.

With Romania well into transition after Ceaușescu’s demise and with promises of change for the better, Belodedici finally felt safe enough to go back to playing for the country’s national team — something he refused to do before out of fear of potential prison time.

“When I left Red Star, I was again approached to come back to Romania to play for the national team. So, I went back,” he said.

“When they invited me to play at the 1990 World Cup, Red Star wouldn’t let me because they didn’t know what my situation was like back home.”

“Since I was considered to be a military officer, the club didn’t know whether I was sentenced for desertion in the meantime. So they didn’t want to let me go until Romania delivered my dossier.”

The 1994 World Cup in the United States was the first and last time he represented Romania at the tournament. In the quarter-finals, Romania lost to Sweden on penalties. Belodedici missed the last penalty that would have kept them in the game.

After several stints in Spain and Mexico, he returned to where he started — to Steaua, finishing his playing career in 2001 with one more domestic title and a cup to his name.

As the country was trying to rid itself of Ceaușescu’s legacy, his dossier became irrelevant, and his defection was largely forgotten.

“I didn’t have too many problems after I came back. An odd communist would approach me to ask things like why did you have to leave, etc. but people greeted me well.”

After his retirement, he was invited to be a part of the Romanian Football Federation, coordinating the national teams and working with youth recruits — where he works to this day. But it did not take long for him to realise that the change only happened on paper.

“The problem with Romanian sports is that, although it seemed like things were going to change, it was actually the same people. The same ones who were in management during the communist times were now entering the managing boards of clubs,” Belodedici said.

“The change only took place in theory. In practice, things remained the same.”

The privatisation of clubs, often done under suspicious circumstances or involving sketchy investors, further impoverished the game. Prospective players — the future Belodedicis, Popescus, Mutus, Hagis — are paying the biggest price.

“Can you imagine that Steaua Bucharest is gone? Dinamo Bucharest is next to last in Liga I and they’ll most likely get relegated. Politehnica from Timișoara is almost gone as well,” he enumerated.

“There are four or five big clubs in total that are no longer what they used to be, because the private owners syphoned off the money from the clubs, and that’s a disaster for the young footballers.”

Belodedici’s Steaua is to this day embroiled in a name dispute and a legal conflict regarding its brand and honours. In 2017, the now privately-owned club had to change its name from FC Steaua București to FC FCSB.

The club’s majority owner, Gigi Becali — whose family was incidentally also deported to Bărăgan as ethnic Aromanians — has accrued significant wealth during the post-Ceaușescu period.

After several investigations by the country’s National Anticorruption Directorate, he was sentenced to prison for land exchange deals with the Romanian Army between 1996 and 1999.

Becali, who is a self-proclaimed nationalist and a sympathiser of the militant revolutionary fascist movement, the Iron Guard, also dipped his toes into politics, serving as a European Parliament member between 2009 and 2013.

“Romania never truly progressed,” Belodedici emphasised. “Each year we get promised that things will get better, over and over again. But it’s been thirty years since, and it simply just keeps worse all the time.”

His illustrious career is in constant contrast with his quiet nature, which led to myths and rumours springing up around him, like the story of how he left Romania right after being awarded the coveted ‘Footballer of the Year’ award, forcing Ceaușescu to wipe out any mention of him from the local press.

In fact, he never got the award.

“I’d always get selected as either the second or third best footballer in the country. In 1988, I came second to Helmuth Duckadam — the goalkeeper who saved four out of five penalties in the 1986 finals. I never got that title,” he said.

Another urban legend says that it was none other than another Romanian superstar, Gheorghe Hagi, who helped him learn Romanian. When asked about it, Belodedici laughed.

“I learned it in school — I started learning Romanian from fifth grade, at age 10.”

“I only met Hagi in 1981, when we were both with the U-21 national team. Hagi also didn’t speak Romanian at home — he spoke Macedonian, I think.”

And contrary to popular belief, he was never called “Deer” due to his graceful tackles.

“I wasn’t called ‘Deer,’ I was called ‘Doe.’ In Serbian it’s ‘srna,’ in Romanian, ‘caprioare,’” he explains, smiling.

It is other nicknames that are much lesser-known, he said.

“When I started playing in the Romanian second league, they called me ‘the Serb.’ They’d chant ‘Sârbule, Sârbule,’ as the Romanians say. They kept calling me that at Steaua and the national team, too.”

“But when I went to Red Star, I was ‘the Romanian’ to everyone,” Belodedici explained.

“My whole life, everyone always asked me, who are you? I’m a minority, I’d reply -- both in Serbia and Romania.”

But the various coincidences in his footballing journey that helped the “two stars” -- Steaua and Red Star -- win their Champions League trophies are what makes him something of a talisman, he believes.

“I managed to win all the big trophies, and to this day I have no idea how that happened. It’s fate, simple as that.”

“With Red Star I won the Inter-Continental Cup, while we lost that game with Steaua. While with Steaua I won the European Super Cup, and with Red Star I didn’t,” he pointed out.

“I still sometimes think, was it me?”

Every weekday, Uncovering Europe brings you a European story that goes beyond the headlines. Download the Euronews app to get a daily alert for this and other breaking news notifications. It's available on Apple and Android devices.