Experts have noticed an increase in cyber-addiction in young people since the start of the pandemic. What is real cyber-addiction and can we do anything about it?

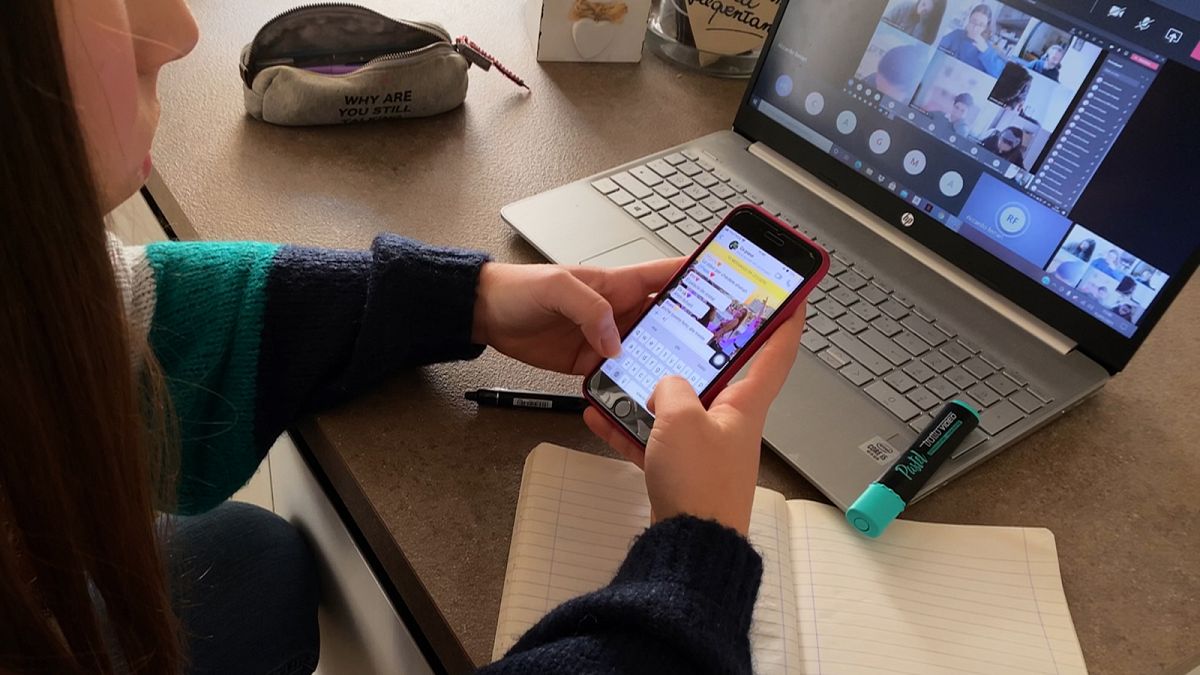

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused problems to all walks of life across every continent. Financial difficulties, high unemployment, pressure on health systems and isolation are just a few of the hardships facing society right now. But one of the less mentioned issues caused by the pandemic is the effect of prolonged and repeated lockdowns on young people and how they are becoming increasingly hooked on the dopamine hit they get from screen time. More and more parents are worried about this. They fear that their children spending hours on computers and phones, gaming and studying, might turn into an addiction.

We decided to talk to two under 20s to see how they are handling screen time in these uncertain times.

Remote education during the pandemic

Benedetta Melegari is a secondary school pupil from Genoa, Italy. She is one of the 1.6 billion students worldwide whose education has been disrupted by COVID-19. Last year she did most of her classes remotely and she still is. She says that since the beginning of the pandemic she has spent "about eight hours a day in front of a computer". She tells me that she hardly used the computer before and she now feels that she "couldn’t live without a phone or a computer".

Remote learning has maintained a certain level of educational continuity during the pandemic, but it is also heavily criticised. Many say it is keeping students glued to screens. However, not everyone agrees with this. Roberto Rebora is an English teacher at Grazia Deledda International School (Liceo Linguistico Internazionale G. Deledda). He thinks that “students tend to reject the screen as they start associating it with many hours of distance learning". Although he does say that "this doesn’t mean they avoid using their phones, because that has become a relatively new way to meet other people, perhaps the only way.”

Benedetta admits that the time she spends on her smartphone has skyrocketed since the pandemic. She spends hours on social media without even realising. She describes the effects as making her "less keen to do things". She tells us that it has affected her sleep, keeping her awake and making her feel agitated.

Her mother, Serena, says the extended screen time means children are interacting less with their families. She is also concerned that so much time on screens will lead to an addiction.

But Serena is not the only one to worry, nor is she the first. In 2017, the local Health Authority in Genoa gathered a pool of experts to study the emerging phenomenon of youth cyber-addiction. We attended their latest virtual meeting.

Margherita Dolcino is the head psychologist at the MySpace project for teenagers and one of the experts in this group. She says they have received "double the amount of requests for support and intervention post-lockdown". In the last three months, they have taken on 10 children identified as cyber addicts.

Cristiana Busso, a psychologist at SERT, the addictions' unit of Genoa's local Health Authority, tells us that their new patients are predominantly young males between 13 and 20 years old. They already had an unhealthy relationship with tech devices before the pandemic. Remote learning did not cause their addiction.

She gave us more insight about tech addiction:

“We don’t suggest measuring technology addiction in terms of time spent in front of the devices. Parents often consider this as the main problem. We might better understand addiction related to the kind of use the youngster makes of the screen. The question we have to ask is how does the kid use the Net and why for so long?”.

Identifying screen addiction

We went to Paris to ask one of the most prominent researchers on cyber addiction, Michaël Stora. He is a psychologist, an author, and founder of the Observatory on Digital Worlds in Human Sciences. According to him, the addiction process starts off slowly, "little by little, the person will do nothing other than play. The relationship with the video game will be similar to other kinds of addiction. The game will become more important than other social activities. Virtual bonds will take over real-life bonds. If in six months, the person can’t overcome this way of functioning, the diagnostic is cyber addiction.”

Stora says 98% of young people suffering from cyber addiction have high IQ’s, but they also often have social and school phobias, or sometimes autistic troubles. He describes video games as a form of escapism for these young people, as often "when these young people are faced with failure, they break down. Video games become a kind of interactive antidepressant".

But video games don't prepare children for the real world. As Stora says, "video games allow them to become virtual heroes, to continue fighting with great results. They succeed, but they're short and easy victories” and that's "the opposite to real life where succeeding takes time".

Heros School

However, Stora is convinced that for these kids, gaming addictions can be turned into an asset. That's why he created 'Heros school' (École des Héros), where a select number of hardcore gamers train to become video game designers.

One of the students at his school is Fidy. Fidy is sixteen and he dropped out of school a year ago. His social skills are impaired by Asperger’s syndrome. His autistic disorder has challenged him and his parents for years.

He spends a maximum of 16 hours a day in front of a screen, yet he himself does not consider that an addiction. He is happy with the way things are. He does say, however, that the time the internet is turned off at night makes him "overwhelmingly sad".

His parents consider technology as more of an ally to him than an enemy. It's a space where he feels good and happy. His father tells me that he considers it more of a "consolation rather than an addiction". Video games are a refuge to Fidy.

It’s too early to analyse the full impact of prolonged social isolation on young people and their screen habits. More time is needed to know whether increased cyber addiction will end with the pandemic and to what extent its effects are reversible. But one thing is for sure, screens are not going anywhere and we may have to get used to a new reality, like Fidy's, where "screens are not another world, they are a part of real-life".