Lawyer Claire Mitchell QC is leading the campaign to pardon and commemorate the voiceless women who were falsely accused of witchcraft and executed in Scotland nearly five centuries ago.

As a Scottish appellate lawyer with over 20 years of legal experience, Claire Mitchell QC recognises a miscarriage of justice when she sees one. What makes the case she is currently pursuing so compelling is that the clients she represents died nearly four centuries before she was born.

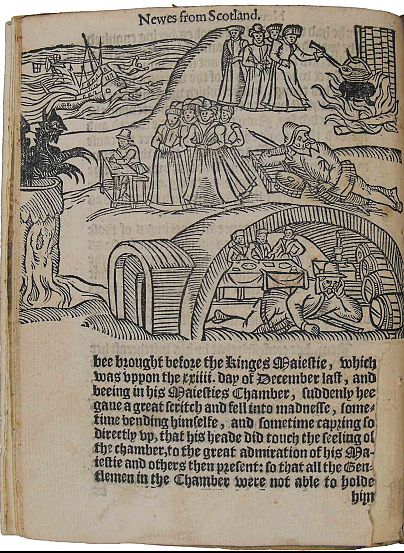

Fomenting with religious fervour, post-Reformation Scotland was a perilous place for women. Deep-rooted fears of witchcraft and devil-worshipping - whipped into a frenzy by figures such as King James VI who wrote extensively on the topic - set the seal on the most prolific campaign of violence against women the country has ever seen.

Over the course of nearly 200 years from the mid-sixteenth to early eighteenth centuries, some 4,000 women were put on trial accused of witchcraft with over 2,000 of them executed. A remarkable feat given its size, Scotland holds the dubious record of carrying out five times more executions of witches per capita than the European average.

It's an injustice that Mitchell wants to set right, going so far as to found a campaign to pardon all those who were falsely convicted of witchcraft, solicit an apology for those accused, and initiate work on a national memorial for all those who fell victim to one of the darkest episodes of Scottish history.

"When I had spoken to people about this idea, I expected complaint, ridicule," Mitchell told Euronews. "I just imagined that people would think that this was a ridiculous idea. I am absolutely delighted to say that I have received overwhelming support, not only within Scotland, but people have contacted me from across the globe."

'Where are the women?'

So, how did this all come about?

Living in Edinburgh's medieval Old Town, with its crooked buildings, cobblestone streets and narrow "closes" (small alleyways with courtyards), you're very aware of the city's past, Mitchell says. It's a history, more often than not, recorded through the prism of the male experience.

"I was walking around Princes Street Gardens. I was looking at the memorials. I just thought, 'Where are the women?' Where were there any statues to women at all in Princes Street Gardens, naming women who have done something?"

There are currently only two statues erected in memory of women in Edinburgh; one for Queen Victoria and the other a local woman and community organiser, Helen Crummy. In fact, there are more monuments in the city dedicated to animals than there are for women, including Greyfriars Bobby, a small Skye terrier of local renown, and a beer-swilling Polish bear named Wojtek who fought in the Second World War and lived out his retirement at Edinburgh Zoo.

"Where I was standing beside Wojtek the bear, I looked down at the area where the Nor' Loch was, where history tells us women were "dooked" [forcibly plunged underwater as a punishment] as witches. They weren't actually but those are the stories that are recorded," says Mitchell.

"I looked down there and thought to myself, 'I know at least 300 women in this very area were killed as witches in a terrible miscarriage of justice and there isn't so much as a plaque or a stone or something to say sorry for it.'"

Visibility of women

The seed of an idea germinated that day as she "stomped home in high dudgeon", Mitchell says. It finally took root this year on International Women's Day on March 8, the day her campaign was officially launched.

The coronavirus pandemic soon began to hit and Mitchell was forced to put the campaign on hold but the Scot soon found a new impetus to stay motivated as she watched the Black Lives Matter movement spread across the globe.

As statues of slave-traders and Confederate generals, offering varnished, one-sided historical perspectives, toppled from their plinths, the core mission of Mitchell's campaign to reclaim history seemed to capture the zeitgeist.

"When that was going on, I thought 'This is the same', as I think it's important for women to have visibility in public spaces and to have their histories told and their stories told. It's not that there weren't women who did fabulous things and should have statues. It's just that history didn't record them."

Legal case

Statues through the centuries have acted as waymarkers of history, prompting the collective remembrance of a person or an event. In the absence of having anything to mark the pernicious witch-hunting that took place across the country, Mitchell's first step has been to build awareness of the plight of the thousands of women long since tortured and put to death.

Her next challenge will be to construct a solid legal argument which she will inevitably have to make to the Scottish government's justice committee in order to finally exonerate them. There is precedence, however, for the kind of pardon and apology she is seeking for Scotland's wrongly-accused witches.

In June 2018, the Scottish Parliament unanimously passed a bill pardoning thousands of gay men in Scotland who had historical convictions for "gross indecency" following an "unequivocal apology" issued by first minister Nicola Sturgeon the previous year.

In Scotland, it was illegal for a man to have consensual sex with other men until a law decriminalising homosexuality was passed in 1980.

"We had passed a law that provided pardons for everybody, living and dead," Mitchell says. "That was actually part of my reasoning when I thought about a pardon because it made it clear that it wasn't just for the living but it was also for the dead.

"I thought it was interesting that it was important to value people's memory and the history of what's happened to them. In a sense, does it matter if a person's been dead 40 years or 400 years at that point?"

'Can you be a witch and not know it?'

While all the personal histories of the women involved are harrowing, two, in particular, have stood out in Mitchell's mind, driving her on to clear their names. The first was an unnamed woman whose trial she read a firsthand account of.

"She said to her torturers, 'Can you be a witch and not know it?' So, she was so defenceless against the charge of being a witch that while these people were torturing her, she thought 'They think I'm a witch. Maybe I am a witch.' I just thought it was so sad that that woman had been put into that situation where she was agreeing with her torturers," she said.

At the time, the authorities' preferred method of torture was sleep deprivation as a means to extract a confession, the accused ultimately losing all grasp of reality. They were also stabbed with pins to find evidence of the Devil's mark.

The other woman was Lilias Adie. Despite having confessed to various crimes of witchcraft, including fornicating with the Devil, she died, presumably from the ordeal of her intense interrogation, in 1704 before her trial could take place.

The depth of public fear at the time is evident in the manner in which her corpse was disposed of. Not content to bury her on the shoreline in a chained box, the villagers put a large slab over her grave to prevent her "revenating," or coming back to life.

"People tend to think witches are a silly caricature - the old woman casting her spells with a cat and pots - and tend to caricature them in a way that you forget that these were just women that this happened to," said Mitchell. "And they weren't a thing to dress up as at Hallowe'en. They were just women going about living their lives."

Symbolically erased

Besides Mitchell's own efforts, recognition of the injustices visited on these women is beginning to break through to mainstream society. In September, for instance, three plaques were unveiled in Fife to commemorate the 380 women - including Adie - who stood accused and were executed in witch trials in Culross, Torryburn, and Valleyfield. It's a start.

It remains an uphill struggle to fully atone for what transpired centuries ago, not least because there is no definitive record of just how many were accused or killed. And unlike Adie, few if any of the women who died are known to have been buried at all. The majority were either burned at the stake or their bodies cremated post-mortem.

"What happened when you were convicted as a witch was that you were obliterated. You were convicted as a witch, you were strangled and then you were burned. Usually, the burning was simply to get rid of the body so you couldn't come back. It was more symbolically erasing you," said Mitchell.

"And that's what happened. These women were successfully erased from history. That's one of the reasons I want to try and bring them back in some way because they were erased".