National authorities and lawyers are embroiled in debate after migrants crossing into Italy were found to be ushered into vans, deported to several countries, and ultimately abandoned outside the EU.

Italy has admitted to informally returning migrants to Slovenia simply by putting pen to paper.

It's an illegal procedure, according to legal experts, and has been found to trigger a chain of transfer that not only leads migrants out of Italy, but out of the European Union, too, by passing them through Croatia on to Bosnia and Herzegovina.

There's no written evidence, no trace, and no publicly available documents.

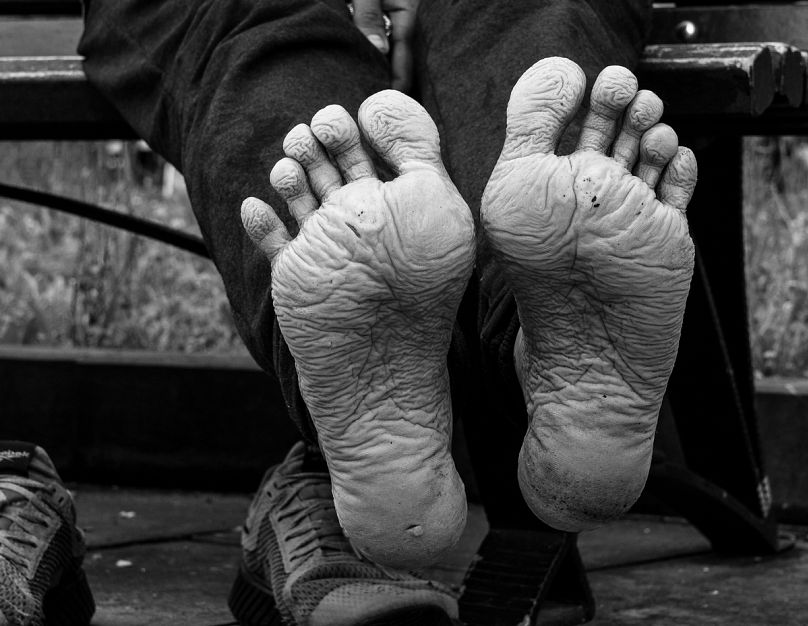

Migrants are simply found at the station in Trieste, Italy, before being ushered into a van and vanishing like ghosts. Reappearing in Bosnia, they are now firmly outside the bloc having often suffered widely reported brutalities from Croatian police.

ASGI, the Italian Association for Legal Studies on Immigration, said this act amounted to illegal rejection, and lawyers in Slovenia agreed.

But Italy's interior ministry was not so quick to concur. It instead defined the rejections as "informal readmission procedures" and argued that yes, they are perfectly legal.

The interior ministry said the procedure does not "involve the drafting of a formal provision" and is actually part of "consolidated practice" that works on the basis of an agreement between Italy and Slovenia from 1996 - eight years before Ljubljana joined the EU.

Italy claims that this agreement can therefore be enacted "even if the intention to seek international protection is expressed [by migrants]."

But on this, the European Commission's stance is clear, telling Euronews that member states cannot transfer asylum seekers to another neighbouring state simply because they arrived from there.

Ahmed's story: from Trieste station to Bosnia in 24 hours

On July 20, Ahmed*, from Pakistan, was found by police in a square in front of Trieste station with two other groups of migrants. They had left Bosnia a few days earlier, attempting the so-called "game".

Taken alongside the others to a tent, the group was fingerprinted and asked to speak with a cultural mediator. Ahmed was guaranteed the possibility of obtaining asylum in Italy.

But by 5 pm, he was transferred to a van and handed over to the Slovenian authorities. Spending the night in a police station, he was given food, had his fingerprints taken again, and was delivered along the chain to Croatian police the following morning.

That evening, at 8 pm, he was abandoned together with his travel companions on the Bosnian border, in the Velika Kladusa area.

READ MORE:

- Mediterranean rescue charities disagree on whether to work during pandemic

- Salvini 'nothing to ashamed of' after senate vote sends him to trial

- 'People can die if we don’t act,' says founder of migrant rescue NGO

Ahmed's story was later retold to ISPIA, an NGO working in Bihać, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

He has now left - but before his departure, he and his travel companions spoke about the violence they say they also suffered at the hands of Croatian police on the Bosnian border. This included the destruction of personal belongings (backpacks, telephones, power banks, etc.), insults, beatings, destruction of documents and clothing (shoes and jackets).

The only document issued by the Trieste border police, and signed by the boys, is a "report of identification, election/declaration of domicile and appointment of the defender made by an investigated person". It included a complaint for illegal entry into the country.

Ahmed managed to hide this document along the way.

The complaint highlights two things: The first, is that Italian police admit that people have entered Italy. The second is that the speed of the readmission procedure does not allow someone to defend themselves from this complaint.

Border authorities in Trieste referred Euronews to the interior ministry when asked about the procedure - which served as further evidence of the sensitivity of the issue. These are matters for high administration and political responsibility, they told us over the phone.

Ahmed's court-appointed lawyer was also never contacted by him, and he expressed surprise that the "rejection" took place at Trieste station, saying: "It seems a bit far away.

"I thought it happened only just beyond the border with Fernetti."

He added that he had never received any calls from any migrants regarding readmission to Slovenia.

Lorena Fornasir, founder of the Shadow Line association that provides food, shelter and comfort to migrants at Trieste station, said stories like Ahmed's were not uncommon. Some, she said, also involve minors, Afghans or Pakistani people from Kashmir, all of whom are protected by international law.

She added: "After they are taken, no one is tracking them anymore. We don't even know if they are deported.

"They become ghosts that then re-emerge in Bosnia, where they send me photos of how they were treated by the Croatian police during the rejection process."

She then recalled an incident last week in which she saw 13 boys who were being taken to Slovenia.

"We couldn't take pictures, the police blocked us," she said. "But we heard the desperate screams and cries of these guys when intercepted by the police."

The problem with this procedure is that it leaves no trace

Migrants are not guaranteed access to the asylum procedure making it impossible to ascertain their possible refugee status, which could ultimately save them from expulsion.

Not only this, but rejections carried out "without formalities" cannot be challenged by migrants, who find themselves at the mercy of the police.

According to Schiavone di Asgi, the whole procedure itself has major flaws. The readmission agreement cited by Italian authorities from 1996 is dubious in its legitimacy and was never actually ratified in law by parliament.

It also does not apply to asylum seekers and contradicts the Dublin regulation on asylum rights in Europe, which was precisely created to avoid border rebounds between one state and another.

But the interior ministry insists there are no violations of asylum rights, and in reference to the risk of "chain rejections" between countries, it says that Slovenia and Croatia are members of the EU, and are therefore deemed safe.

The Slovenian administrative court, however, which sentenced national authorities in July over a violation of asylum rights to a 24-year-old Cameroonian, did not agree. In this case, authorities had taken the migrant back to Croatia, where he was eventually moved on to Bosnia.

Judges in the July ruling said the principle of non-rejection - a cornerstone of international, community and national law - had been violated because it did not take into account the real risk of the individual being subjected to torture or inhumane treatment in Croatia.

There is a wealth of evidence of violent behaviours from Croatian police that has been gathered by journalists, NGOs, activists, volunteers and politicians. In the case of the Cameroonian, it was found the informality of the procedure meant that he was unable to access necessary legal protection.

Slovenia uses the same justification as Italy

Slovenian authorities have justified these "readmissions" in a similar method to Italy - by citing a bilateral agreement signed in 2006 with Croatia.

However, the Slovenian Ombudsman, which participated in the Cameroonian's trial, indicates that this agreement also goes "against the European legal order".

Most rejections in Europe today, it writes, are justified with similar bilateral agreements - all of which can be challenged in court.

The PIC, the legal centre of protection for human rights in Slovenia, also agrees with Italy's ASGI lawyers.

"This is a procedure that does not comply with European law. There is no written decision as to why or where migrants are reported, there are no procedural guarantees, nor is it possible for migrants to legally appeal against this decision," Katarina Bervar Sternad, director of the PIC, told Euronews.

"According to the agreement between Slovenia and Croatia, even minors are not excluded, and the Slovenian police are not sanctioned unless they inform the social services in case the procedure involves minors, as required by the protocol."

READ MORE:

- Open Arms migrant boat: Salvini concession as children leave stranded vessel

- Why did Sea-Watch 3 decide to enter Italian territorial waters?

- What's it like living in Italy as a migrant?

Statistics from Slovenian police indicate that Italian authorities reported 158 migrant crossings in 2018, and a further 147 in 2019. Almost all of them were then handed over to Croatian police.

In the first six months of 2020, the number of "readmissions" from Italy to Slovenia rose to 291.

Clarifications from the European Commission and UNHCR

When questioned on the matter, a spokeswoman for the European Commission told Euronews that, according to the EU directive on the return of illegal immigrants - which came into force in 2009 - member states can continue to apply bilateral agreements signed before that year.

ASGI points out that although the possibility of applying these readmission agreements is provided for by both European Union law and national law, these readmissions can never violate the common asylum system, or be carried out in violation of fundamental human rights.

"The right of states to reject those who do not have permission to enter and to expel those who are not entitled to remain on national territory, albeit lawful as an expression of the principle of state sovereignty, has specific limits," ASGI wrote in a statement.

In short, if a foreigner is inside a state - even irregularly - but asks that the conditions for obtaining asylum or international protection be ascertained, no country can take then back and deprive them of access to the procedure.

Urged on this point, the EU Commission pointed out that the European Asylum Regulation does not allow the transfer of asylum seekers to a neighbouring member state, even if they come from there.

"If the member state considers another member state to be responsible for examining the asylum application, the former will still have to comply with the procedures of the regulation before transferring the applicant," the Brussels spokeswoman said.

The European Court of Human Rights, over the years, has intervened to make the principle of non-rejection binding for all member states. Schiavone di Asgi asked the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, UNHCR, to monitor the situation in Trieste by sending at least one official.

UNHCR staff in Italy told Euronews that the number of people readmitted to Slovenia had increased in comparison to the previous year, and encouraged a "check with the competent authorities the news concerning the readmission to Slovenia also of people who intend to seek asylum in Italy".

"Each state has the right to exercise control of its borders and to manage irregular flows of people, but, at the same time, it must avoid making excessive or disproportionate use of force and ensure the functioning of systems that allow it to take charge of asylum applications according to orderly procedures," the note from UNHCR said.

*Ahmed's name has been changed to protect the subject's anonymity