We need to see like birds in order to protect them, say the ornithologists suggesting a ‘simple’ redesign.

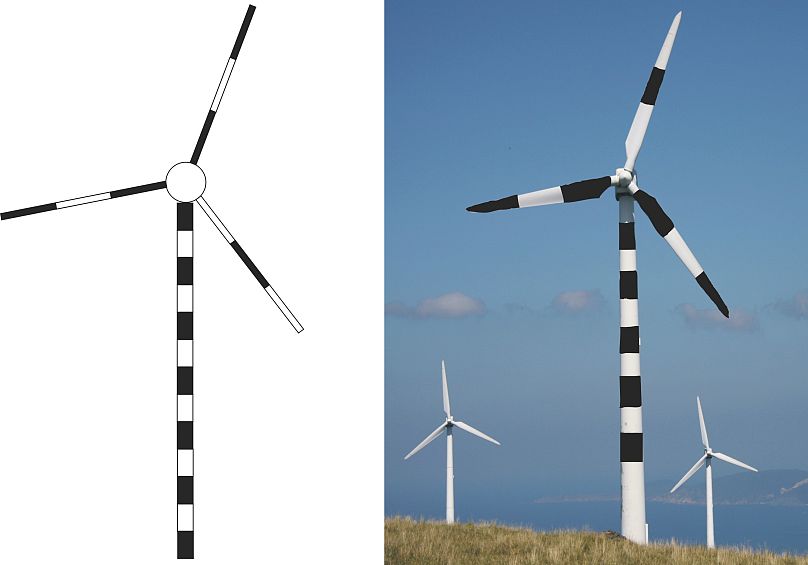

Painting wind turbines with black and white stripes could prevent seabirds from colliding with them, a new report suggests.

The risk of seabirds being struck by turbine blades is a major consideration for offshore wind farms (OFWs), so any mitigating measures are very welcome.

This isn’t the first time that researchers have considered making wind turbines stand out more. In 2020, a Norwegian study found that painting one blade black could cut bird strikes by up to 70 per cent.

But the key to making OFWs more conspicuous to birds is to see like a bird.

Professor Graham Martin, an ornithologist specialising in the sensory world of birds, and Alex Banks, an ornithology specialist at Natural England have delved even deeper into avian vision in their study, published in the Global Ecology and Conservation journal.

They argue that increasing the internal visual contrast of wind turbines using achromatic patterns (making them stripy, in other words) should make the skies even safer for birds.

Why do birds fly into wind turbines?

Ornithologists have long observed that “a bird is a bill guided by an eye.” Its vision is driven by the need to forage for food, and detect predators. Looking out for pylons hasn’t been so much of a priority, historically.

In the same way that humans are vulnerable to car crashes - movement “beyond the evolved limits of our perception” - birds are susceptible to new obstructions, say the researchers, especially in open air space.

Larger birds like eagles and vultures have the highest spatial resolution of any animal, meaning they can spy incredibly small details from afar. But they’re particularly vulnerable to collisions because their eyes are trained downwards on prey.

Though the limits of visibility vary, the authors point out that in all bird species, the direction of highest spatial resolution projects laterally - on both sides of the head - rather than forwards.

Why are birds more likely to spot stripy wind turbines?

Unlike on accident-prone roads, we can’t simply put up warning signs or speed restrictions for birds. But could we be doing more visually to protect them?

“We see the world in a particular way, and we flatter ourselves that that’s how the world is,” Professor Martin tells Euronews Green. “But we are prisoners of our own senses; other animals will see the world and extract other sorts of information.”

While people might think that painting a wind turbine in bright colours is the surest way to ward our winged friends off, there’s good reason that the researchers have gone in a monotone, stripy direction.

Birds use forward vision to control their flight towards a target, especially to figure out the time-to-contact. They use relatively low spatial resolution vision to do so, which is more attuned to changes in the ‘optical flow pattern’ than any particular details.

So a turbine with blades divided into thirds of black and white - alternating to create the most flicker when they’re rotating - is the best way to catch birds’ attention.

This internal contrast is more effective than trying to make the turbine contrast with its background, as the sky is constantly changing colour and brightness. And black and white - both absorbing and reflecting light - are the most contrasting combination.

Will policymakers take the findings on board?

Rolling out wind farms at sea and on land is key to Europe hitting its renewable energy targets.

At the same time, “thousands of birds are being killed out at sea and something should be done to offset that,” says Professor Martin. Especially as developers eye up new waters - round the west coast of Scotland for example, where new bird populations will become vulnerable.

“Hopefully we’re stimulating debate as to what's to be done,” he says, and the turbine design is a “really simple, straightforward thing to do.”

It can be implemented at the manufacturing stage, and doesn’t interfere with statutory requirements to make offshore turbines visible to ships and aircraft (i.e. with flashing red and yellow lights).

The researchers add that more work is needed to understand the impact on bird migration as well as human marine users.