Last year saw a record of wind energy installations across Europe, albeit still lower than needed to meet Europe’s 40% renewables target by the end of this decade. Nevertheless, the rush to achieve energy independence and the currently installed 236 GW and the 116GW (source: Wind Europe) planned for the next four years speak of Europe’s ambition to boost wind power. But how can the industry keep these ambitions high when winds are low?

Wind droughts – a new challenge to Europe’s energy system?

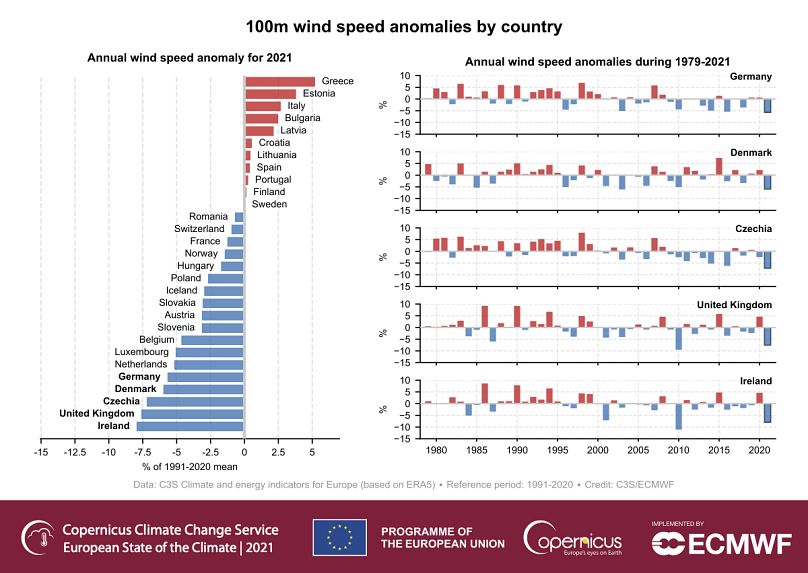

In 2021, across parts of north-western and central Europe, wind speeds were unusually low, with some of the lowest speeds recorded in the last 40 years throughout the summer, according to the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S). In some places in the UK, the Czech Republic, Ireland, Germany, and Denmark annual wind speeds were even 10 per cent lower than the averages for the last 30 years, C3S data shows.

Figure 2. (Left) Annual average anomalies of 100 m wind speed in 2021, relative to the 1991–2020 reference period, by country. (Right) Time series of annual average 100 m wind speed anomalies for the five countries with the largest negative anomaly in 2021. In all plots, anomalies are expressed as percentages of the average for the 1991–2020 reference period. Data source: C3S Climate and energy indicators for Europe derived from ERA5.

“There were prolonged periods of high pressure in the Northern Atlantic around Europe” says Dr. Hannah Bloomfield, climate risk researcher at the University of Bristol, UK. “These are conditions that normally lead to low winds, we call them blocking events, when these masses of high-pressure air just sit there,” says Dr. Bloomfield, who adds that the UK repeatedly recorded such blockages over last summer. Scientists call these wind droughts, and although not as dramatic as storms or tornadoes, they are still considered an extreme weather event.

Although last year’s wind drought is mainly associated with climate variability according to Dr. Bloomfield, it is also important to note that climate change can play a role in influencing wind regimes in the long term. But depending on the climate scenario wind speeds might increase or decrease. The IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report suggests that there is a 8 out of 10 chance that average wind speeds over Europe’s Mediterranean region will decrease, and about a 5 in 10 chance that this will happen in Northern Europe if global temperatures rise by 2 degrees beyond 2050. Dr. Bloomfield explains that this might happen as the Arctic is warming up at a much faster rate than lower latitudes, closing in the temperature differences that influence wind behaviour. In other words, the smaller temperature differences become, the weaker winds might become too.

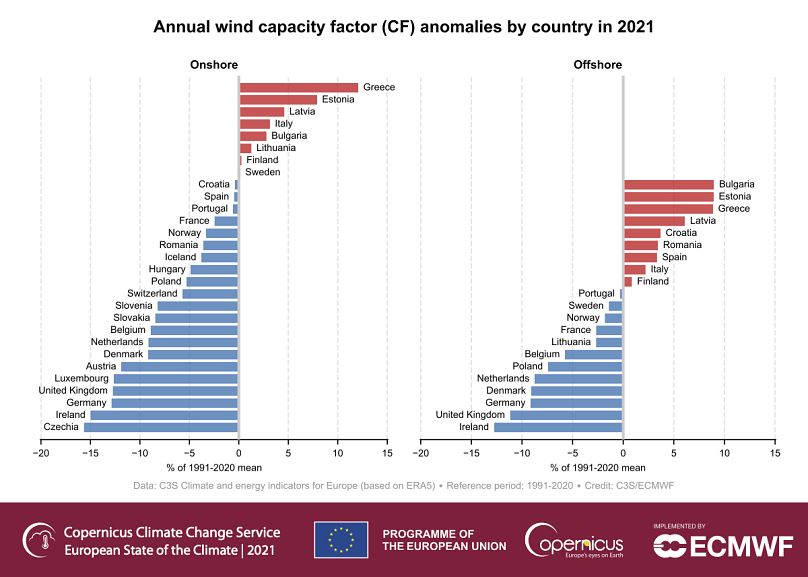

A wind turbine’s energy production is directly linked to the cube of wind speed. In other words, the change in wind speed becomes a three-fold change in energy output. Because of this relationship, even a small change in wind speed can have a major impact on the power sector, and consequently, on Europe’s capacity to boost its renewables wind portfolio.

Figure 3. Annual anomalies in wind capacity factor (CF) by country in 2021, relative to the 1991–2020 reference period, for onshore (left) and offshore (right) wind power generation. Anomalies are expressed as percentages of the 1991–2020 average. Data source: C3S Climate and energy indicators for Europe derived from ERA5.

The low winds of last year caused Britain, Germany and Denmark to use only 14 per cent of their installed wind capacity between July and September, compared to the usual 20-26 per cent of previous years, according to Reuters. In the first half of last year, in Germany in particular, wind energy outputs were 25 per cent lower (46.8 TWh) compared to the same period of 2020 (59.4TWh), says a Forbes report, pushing more demand onto fossil-fuel based plants and boosting the country’s carbon emissions from electricity by 25 per cent.

Managing variability

According to Wind Europe, the association promoting wind energy, the low winds episode is not necessarily surprising, and the shortage in the summer was compensated by the winter winds. “There are always slight differences in the wind resource year-on-year,” says Christoph Zimpf, press and communications manager at Wind Europe. “2021 has been slightly lower than 2020 which had been an extremely good wind year with strong winds in spring. Over most of last year it had seemed that 2021 would end as a pretty poor wind year, but storms in November and December spurred the full-year generation result. It landed within the expected band of year-on-year variation.”

Being able to tackle these dry spells remains important for the renewables industry that needs to step up and help Europe quickly end its dependency on oil and gas. On May 18, the European Commission published its REPowerEU Action plan as a policy response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. “The Commission is crystal clear that the over-reliance on fossil fuel imports from Russia and elsewhere must end,” says Zimpf. The massive expansion of domestic renewables is one of the three pillars of the plan, Zimpf explains, alongside finding new sources for energy imports and boosting energy efficiency. “Wind energy is central to this […]. By 2050 the Commission wants wind to be 50 per cent of all electricity used in the EU. Today it is 15 per cent,” says Zimpf. “In the medium-term wind energy is set to accelerate significantly and to help replace imported fossil fuels. To this end, the European Commission wants to raise the EU’s installed wind energy capacity from 190 GW today to at least 480 GW by 2030.”

The Brussels announcement was followed by Germany, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Belgium signing a €150 bn deal to build at least 150GW of offshore wind facilities by 2050. With so many plans on the table, and with the REPowerEU plan designed to shortcut the red tape on approving wind projects, improving the efficiency of wind power production in the face of climate variability is gaining more attention.

“The wind drought that has affected most of central and western Europe in 2021 shows the importance climate data has in managing our energy mix,” says Dr. Carlo Buontempo, director of C3S. “Understanding what the likelihood of these events is and whether their frequency is likely to change will become of greater importance as the installed capacity for renewable grows. The recent observations and the current predictions have not significantly altered the potential to boost wind energy production in Europe. They simply made more evident the existence of some vulnerabilities and risks that need to be managed. The data and tools that C3S provides will help the industries and the policymakers in such a process.”

Dr. Bloomfield says that predicting low winds a long time ahead remains tricky, though many scientists are producing datasets that can help the wind energy industry better adapt to the future. “It has become easier to make long term risk assessments for wind energy sites. I think the industry could really benefit from the energy meteorological community,” says Dr. Bloomfield. “Being open and coming to organisations like Copernicus with their problems could be very useful in guiding the science community to look at issues that are relevant for the industry.” Wind energy producers can develop ways to integrate scientific observations and predictions when they make decisions, which will help with managing the challenges of climate variability, explains Dr. Buontempo.

Despite the losses in wind energy production last year, countries managed to find other sources of energy to close the gap. Germany tapped into its solar power, while the UK used its ties to energy systems in France and Norway to top up its production. With so much variability to manage, wind plays an important part in Europe’s renewables portfolio, but is not the only player, as Wind Europe suggests. “Generally speaking, Europe’s renewable energy system of the future will need all renewable energy sources […],” says Zimpf. “Wind and solar are natural partners: wind energy generation is usually strongest in autumn, winter and spring – and rather low in summer, just when solar energy generation reaches its peaks. In that sense, the two technologies are complementary. Nevertheless, reaching higher shares of renewables in the energy system they will have to be linked to battery storage and other storage media such as renewable hydrogen. Both technologies are quickly reducing costs and will soon be available at scale.”