The world-class research lab will look at developing new technology to resurrect species that are long gone.

Scientists in Melbourne, Australia are looking to bring the extinct Tasmanian tiger back to life.

A world-class research lab for ‘de-extinction’ and marsupial conservation is being built at the University of Melbourne after a €3.4 million donation.

“Thanks to this generous funding we’re at a turning point where we can develop the technologies to potentially bring back a species from extinction and help safeguard other marsupials on the brink of disappearing,” says Professor Andrew Pask from the university’s School of Biosciences.

The gift will be used to establish the Thylacine Integrated Genetic Restoration Research (TIGRR) lab which will develop new technologies that could bring the Tasmanian tiger back from extinction.

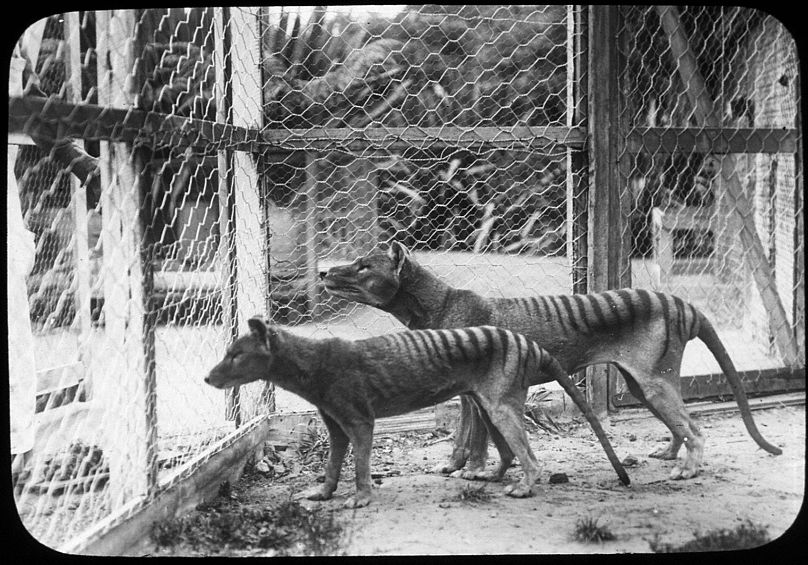

These creatures once roamed across Australia but were confined to the island of Tasmania when Europeans arrived in the 18th century. Colonists hunted them to extinction with the last known individual dying in captivity in 1936.

“Of all the species proposed for de-extinction, the thylacine has arguably the most compelling case,” Pask explains.

“The Tasmanian habitat has remained largely unchanged, providing the perfect environment to reintroduce the thylacine and it is very likely that its reintroduction would be beneficial for the whole ecosystem.”

More tools to prevent extinction

So far scientists have sequenced the Tasmanian tiger’s DNA giving them a “blueprint on how essentially to build a thylacine.” Bringing the species back would require them to understand the code from start to finish.

Cells from the Tasmanian tiger’s closest living relative, the mouse-like dunnart, could then be edited to revive the species.

The new funding will allow the lab to move forward in three key areas: improving their understanding of the animal’s genome, developing techniques to make an embryo and transferring that embryo into a surrogate host.

But alongside bringing the Tasmanian tiger back from extinction, the advances they make could also help other threatened species. At least 39 Australian mammal species have gone extinct in the last 200 years and nine more are currently listed as critically endangered.

Pask says the tools and methods developed in the TIGRR Hub will have “immediate conservation benefits” for marsupials and provide a means to protect against the loss of species that are threatened or endangered.

“While our ultimate goal is to bring back the thylacine, we will immediately apply our advances to conservation science, particularly our work with stem cells, gene editing and surrogacy, to assist with breeding programs to prevent other marsupials from suffering the same fate as the Tassie tiger.”