A new project in the south of Spain is studying whether the European bison can help reduce the risk of wildfires by clearing away scrubland that fuels blazes.

Wildfires in Spain raze an average of nearly 100,000 hectares a year.

And the problem is only getting worse. In the southern region of Andalusia, the number of large fires – more than 50,000 hectares in size – has almost doubled in the past 40 years.

But unexpected help may be at hand – the European bison. Although the large herbivore went extinct in the Iberian peninsula 10,000 years ago, its numbers have bounced back thanks to the work of the European Bison Conservation Centre of Spain.

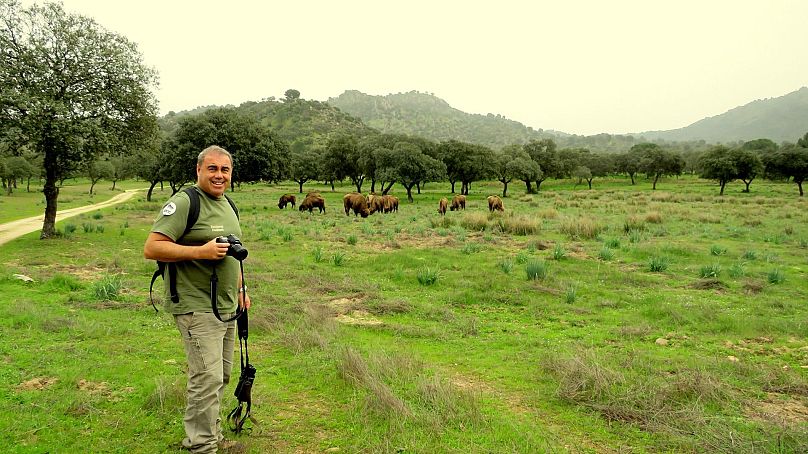

Founded in 2008 by veterinarian Fernando Morán, the centre has helped reintroduce bison to several sites across the country. From an initial herd of 24, there are now 153 bison in Spain. The latest project is being carried out in a 1,000-hectare reserve in Andújar, Andalusia.

In this case, the goal is not just to reintroduce the animal, but also to study whether it can help reduce the risk of wildfires.

Bison are nature's firefighters

Morán has been granted permission from the Andalusian regional government to carry out a one-year investigation into the role bison can play in preventing wildfires by clearing away the scrubland and vegetation that fuel blazes.

Bison are particularly well-suited for this task – they can break through dense undergrowth, they create bare soil patches by wallowing and they have a voracious appetite.

“One of the characteristics of the animal is that it eats wood, shrubs, bushes, tree vegetation, leaves, branches – which is all combustible material in our country,” explains Morán. “If no one eats it or clears it away, it is susceptible to burn. And what it doesn’t eat, it breaks either by trampling or smashing it with its head.”

What’s more, it does this “on a massive scale because it is a very large animal,” says Morán.

This is where the European bison has an advantage over other grazing animals, like sheep and goats. Weighing up to 1,000 kilos, the bison can break through the thick undergrowth that smaller herbivores cannot access. More importantly, it eats up to 35 kilos of vegetation in a single day – the equivalent to 12,500 kilos a year.

“It’s a natural firefighter or wild firefighter that nature has assigned,” he says.

The idea of bison grazing in modern Spain may seem novel, but Morán says this was the norm for around 1.2 million years. Bison are even depicted in the 36,000-year-old cave paintings of Spain’s famous Cave of Altamira.

According to Morán, reintroducing the European bison is a way to restore the natural balance that was lost when the species, and other large herbivores, such as elephants, wild horses and rhinoceroses, went extinct on the Iberian peninsula.

“If you get rid of the bison or large herbivores, you are only going to have forests and shrubland,” he says.

Rural exodus and climate change

Restoring this balance has become particularly urgent in the wake of Spain’s depopulation crisis. As more people leave for the cities, land previously used for farming and other activities has become overgrown, which increases the risk of wildfires.

“As rural areas are abandoned, there is a build-up of combustible material and this means that fires are becoming increasingly dangerous and increasingly big,” explains Javier Madrigal, a professor of forest management at Madrid’s Polytechnical University.

According to a Greenpeace report, the area susceptible to fires in Spain is growing at an average rate of more than 64,500 hectares a year.

This problem is compounded by climate change, which is causing extreme weather conditions in Spain. The first five months of 2020 were the hottest on record, while the number of heatwaves has doubled in the last decade, according to Spain’s weather agency Aemet.

The combined impact of the rural exodus and climate change is leading to “wildfires of a scale previously unheard of in Spain that appear more and more like those in Australia and California,” says Madrigal.

Making matters worse is the lack of forest management. More than 81.52 per cent of the forested area in Spain does not have any forestry regulation.

“On the one hand, there is a lack of planning, and on the other, a real lack of investment. Even if there are plans, in most cases, they are not carried out,” says Madrigal.

Morán believes that as “natural firefighters,” bison could fill this gap, carrying out the costly work typically performed by “teams of firefighters, huge machinery, helicopters and planes.”

Madrigal, however, is more cautious. While he says the project is “encouraging,” he believes it is only part of the solution.

The problem of no recognition

The investigation in Andujár has been running for six months, and although it’s too soon to reach conclusions, Morán says the early signs are positive. The animals – which were transported from Poland – have adapted to the new climate and vegetation of Andalusia.

None have fallen ill, and more promising still, one of the females is pregnant – something that would not have happened in unfavorable conditions.

The challenge now is to see how the animals will fare in Andalusia’s scorching summer, where temperatures can reach 40°C in the shade.

If successful, Morán hopes to expand the project to more areas. But there’s a catch.

The European bison has been extinct for so long that it is no longer considered an endangered species. There is no state funding for conservation projects, and because it is not recognised as a native animal, it cannot be released into the wild.

“Conservation is done privately,” explains Morán. “The people do it because they want to, but there is no support.”

Poland and Romania are the only EU countries that have a state conservation program, but Morán is hopeful this will change. In the meantime, he is working with environmentalists, politicians and scientists to ensure the future of the species in Spain.

“When I wake up in the morning, I think there are a lot of people who are getting up to be a burden to the planet, not because they want to, but because it’s their job. I like to think that I’m waking up to do the complete opposite.”