28 November: Happy Letter Writing Day!

It’s Letter Writing Day, which is observed annually on 28 November.

The celebration came about in 1922, when the first skywriting advertisement was created by Captain Cecil Turner for the Vanderbilt Hotel in New York City. It was a success, resulting in 47,000 phone calls for the hotel.

Since we can’t all go out and create our own skywriting messages (more’s the pity), the day now stands as a reminder that we can still pen messages on paper and send letters.

Still, we’re not going to win many of you over, because since the first ever handwritten letter, which is thought to have been sent by the Persian Queen Atossa in around 500 BC, the practice of sending written communication has gradually become something of a lost art.

So, to celebrate, here are seven letters you may not have read that deserve your attention. They’re not necessarily the most well-known or history-altering of letters, like Emile Zola’s "J’Accuse" or Martin Luther King Jr.’s letter from Birmingham jail. Nonetheless, these are only a few examples which can remind you of the unique joys and of the importance of sending a letter.

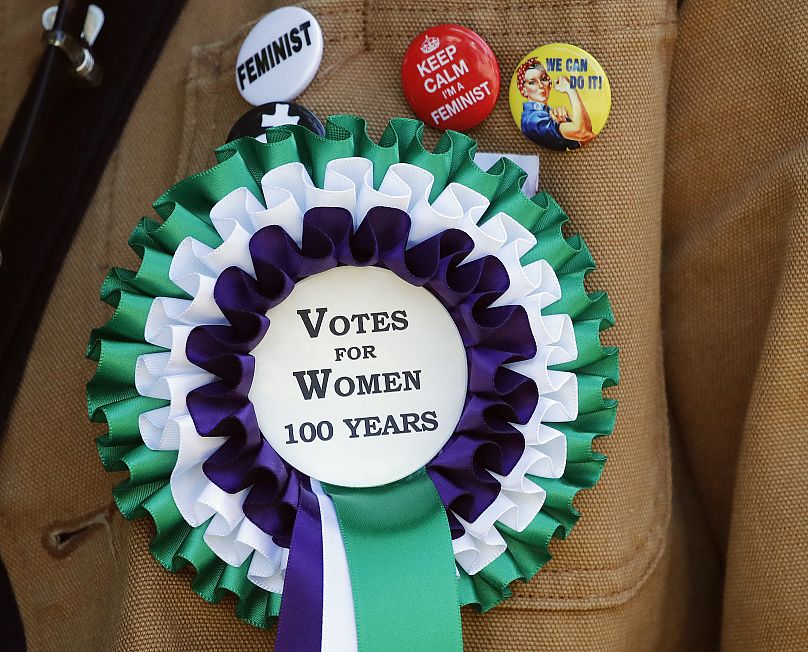

1. Options

A letter sent to the Telegraph in 1913:

Sir,

Everyone seems to agree upon the necessity of putting a stop to Suffragist outrages; but no one seems certain how to do so. There are two, and only two, ways in which this can be done. Both will be effectual.

- Kill every woman in the United Kingdom.

- Give women the vote.

Yours truly,

Bertha Brewster

2. Burn

Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw to Winston Churchill:

Have reserved two tickets for my first night. Come and bring a friend, if you have one. Shaw.

Churchill’s reply:

Impossible to come to first night. Will come to second night, if you have one. Churchill.

3. The cheek

Author H.G. Wells discovered that he had taken the hat of the mayor of Cambridge, instead of his own. He sent the following note to the mayor:

My dear Mayor,

I stole your hat. I like your hat. I shall keep your hat. Whenever I look inside it I shall think of you and your excellent dry sherry, and of the town in Cambridge, which is older than the university. I take off your hat to you.

H. G. Wells

4. Ouch

A short, succinct epistolary reply from director Alfred Hitchcock to an angry letter from a man whose daugter wouldn’t go near a shower after having seen Psycho:

Send her to the dry cleaners.

5. Go Johnny, Go

A letter sent on 15 October 1986 from American astronomer Carl Sagan to singer songwriter Chuck Berry, on behalf of the Voyager Interstellar Record Committee:

Dear Chuck Berry,

When they tell you your music will live forever, you can usually be sure they’re exaggerating. But Johnny B. Goode is on the Voyager interstellar records attached to NASA’s Voyager spacecraft – now two billion miles from Earth and bound for the stars. These records will last a billion years or more.

Happy 60th birthday, with our admiration for the music you have given to this world...

Go Johnny, go.

Carl Sagan

6. Cover letter

After working in advertising as a copywriter in New York City, Robert Pirosh moved to Hollywood in 1934 with dreams of becoming a screenwriter. He sent the following cover letter to all of the directors, producers and studio execs he could think of. Pirosh went on to collaborate with the Marx Brothers, and won an Academy Award in 1949 for Best Writing, Story and Screenplay (as it was then known) for the World War II drama Battleground.

Dear Sir:

I like words. I like fat buttery words, such as ooze, turpitude, glutinous, toady. I like solemn, angular, creaky words, such as straitlaced, cantankerous, pecunious, valedictory. I like spurious, black-is-white words, such as mortician, liquidate, tonsorial, demi-monde. I like suave “V” words, such as Svengali, svelte, bravura, verve. I like crunchy, brittle, crackly words, such as splinter, grapple, jostle, crusty. I like sullen, crabbed, scowling words, such as skulk, glower, scabby, churl. I like Oh-Heavens, my-gracious, land’s-sake words, such as tricksy, tucker, genteel, horrid. I like elegant, flowery words, such as estivate, peregrinate, elysium, halcyon. I like wormy, squirmy, mealy words, such as crawl, blubber, squeal, drip. I like sniggly, chuckling words, such as cowlick, gurgle, bubble and burp.

I like the word screenwriter better than copywriter, so I decided to quit my job in a New York advertising agency and try my luck in Hollywood, but before taking the plunge I went to Europe for a year of study, contemplation and horsing around.

I have just returned and I still like words.

May I have a few with you?

Robert Pirosh

7. D'Arline

In June 1945, Arline Feynman, the wife of influential physicist and Nobel Prize winner Richard Feynman, died of tuberculosis. 16 months later, Feynman wrote the following letter, which remained sealed until after his death in 1988:

D’Arline,

I adore you, sweetheart.

I know how much you like to hear that — but I don’t only write it because you like it — I write it because it makes me warm all over inside to write it to you.

It is such a terribly long time since I last wrote to you — almost two years but I know you’ll excuse me because you understand how I am, stubborn and realistic; and I thought there was no sense to writing.

But now I know my darling wife that it is right to do what I have delayed in doing, and that I have done so much in the past. I want to tell you I love you. I want to love you. I always will love you.

I find it hard to understand in my mind what it means to love you after you are dead — but I still want to comfort and take care of you — and I want you to love me and care for me. I want to have problems to discuss with you — I want to do little projects with you. I never thought until just now that we can do that. What should we do. We started to learn to make clothes together — or learn Chinese — or getting a movie projector. Can’t I do something now? No. I am alone without you and you were the “idea-woman” and general instigator of all our wild adventures.

When you were sick you worried because you could not give me something that you wanted to and thought I needed. You needn’t have worried. Just as I told you then there was no real need because I loved you in so many ways so much. And now it is clearly even more true — you can give me nothing now yet I love you so that you stand in my way of loving anyone else — but I want you to stand there. You, dead, are so much better than anyone else alive.

I know you will assure me that I am foolish and that you want me to have full happiness and don’t want to be in my way. I’ll bet you are surprised that I don’t even have a girlfriend (except you, sweetheart) after two years. But you can’t help it, darling, nor can I — I don’t understand it, for I have met many girls and very nice ones and I don’t want to remain alone — but in two or three meetings they all seem ashes. You only are left to me. You are real.

My darling wife, I do adore you.

I love my wife. My wife is dead.

Rich.

PS Please excuse my not mailing this — but I don’t know your new address.

Happy Letter Writing Day.