Once forgotten in the British military archives, the 200-year-old love letters finally saw the light of day, thanks to a Cambridge University professor.

They never reached the people they were destined to: letters written in the 18th century to French sailors during the Seven Years' War between France and Great Britain have finally been opened, providing both intimate and historical evidence.

Initially considered to be documents of no military interest, these 104 letters were eventually transferred to the British National Archives, where they remained forgotten in a box until they caught the attention of Renaud Morieux, a History Professor at Cambridge University.

"I simply asked to consult this box out of curiosity", the reacher said. His findings were subsequently published on Tuesday in the academic journal, Annales Histoire Sciences Sociales.

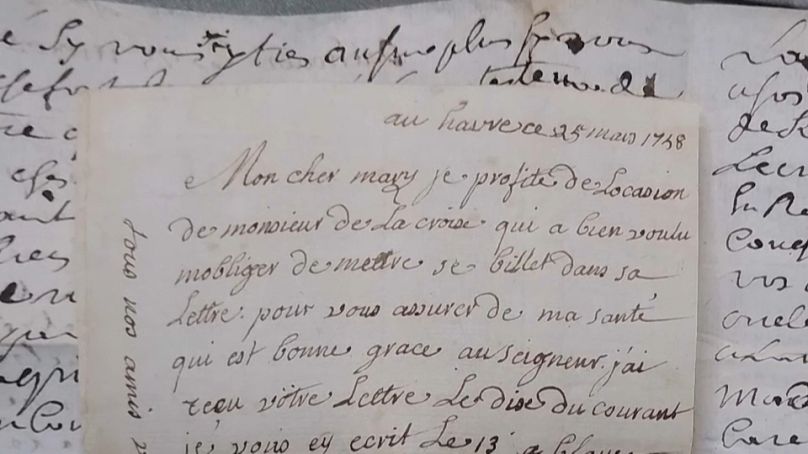

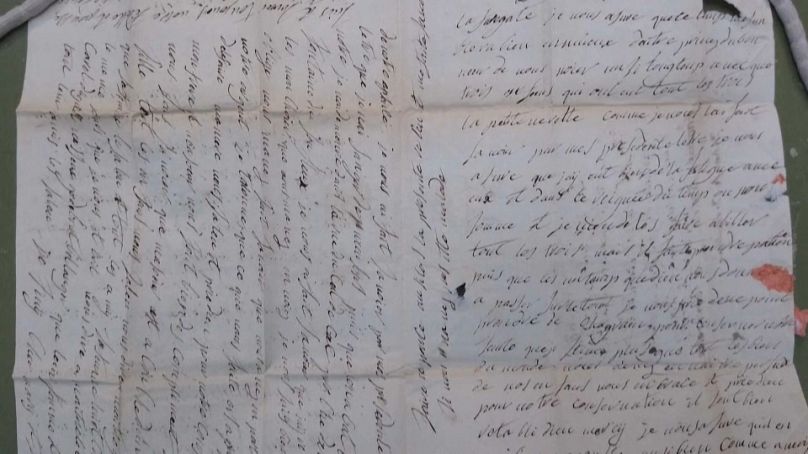

"I realised that I was the first person to read these very personal messages", grouped in three piles and held together by ribbons.

"Their recipients weren't so lucky and it was very moving", he explained, adding that these letters contain "universal human experiences".

An insight into 17th-century women's expressions of love

Written mainly by women, they bear witness to the experience of wives, mothers and fiancées in wartime, forced to run the household alone and make decisions in the absence of their men.

Renaud Morieux identified each of the 181 members of the frigate Galatée, a quarter of whom had been recipients of these letters, and also conducted genealogical research on the sailors and letter writers.

In 1758 alone, a third of France's sailors were captured by the British. Over the entire period of the Seven Years' War, won by the alliance led by Great Britain and Prussia, 65,000 were detained by the British.

Many died of disease and malnutrition, while others were eventually released.

During this period, letters were the only way their families could try to contact them.

"These letters are about universal human experiences, they're not unique to France or the 18th century," added Professor Morieux.

"They reveal how we all cope with major life challenges. When we are separated from loved ones by events beyond our control like the pandemic or wars, we have to work out how to stay in touch, how to reassure, care for people and keep the passion alive," said the historian.

"Today we have Zoom and WhatsApp. In the 18th century, people only had letters but what they wrote about feels very familiar."

Love from beyond the grave

A letter from the wife of an officer, another from a mother reproaching her son for not writing to her more often... these letters were seized by the Royal Navy during the war that pitted the British against the French between 1756 and 1763 over their colonial possessions.

"I could spend the night writing to you... I am your forever faithful wife. Have a good evening my dear friend. It is now midnight. I think it's time for me to rest," wrote Marie Dubosc in 1758 to her husband Louis Chambrelan, first lieutenant of the French frigate Galatée, captured by the British.

Louis never received the letter and his wife died the following year, almost certainly before he was released by the British.

In another missive dated 27 January 1758, the mother of young sailor Nicolas Quesnel from Normandy takes him to task for his lack of communication.

"I think more about you than you about me... In any case, I wish you a happy new year filled with blessings of the Lord," 61-year-old Marguerite wrote in a letter probably dictated to someone else.

"I think I am for the tomb, I have been ill for three weeks. Give my compliments to Varin (a shipmate), it is only his wife who gives me news of you," she added.

But the Galatée, which left Bordeaux for Quebec, was captured in the Atlantic and taken to Plymouth, on the south coast of England, and then finally to Portsmouth.

The letters followed the ship from port to port until it was captured, before also arriving in England.