Pope Francis is the latest public figure to become an unlikely star – or victim – of digital technology’s ever growing tentacles, as fabricated AI-generated images of the Holy Father have been taking social media by storm.

In an image that has already racked up tens of thousands of views, Pope Francis can be seen sitting on the edge of a sleek sports car, flaunting a pair of trendy sunglasses and spotless white shoes.

The picture would seemingly bolster the Pope’s relatable demeanour, as it shows the 86-year-old Pontiff exuding a braggadocio-like confidence. Except, there’s a catch – it isn’t real.

Pope Francis is the latest public figure to become an unlikely star – or victim – of digital technology’s ever-growing tentacles, as fabricated AI-generated images of the Holy Father have been taking social media by storm.

Pope Francis and AI is a pairing few had on the cards. Indeed, the Pontiff recently gave a speech where he urged tech developers to “act ethically and responsibly”. The bigger question is: Is it a match made in heaven – or hell?

‘Tech developers must act responsibly’: The Pope’s comments on AI

Towards the end of last month, a deluge of fake AI pictures depicting Pope Francis in a variety of comedic – or even outright sacrilegious – situations have been flooding social media, especially on Twitter.

Some of the most prominent include images of the Holy Father donning an oversized white puffer coat, using a MacBook, DJing, or riding a motorbike. The first of these alone garnered 6.5 million views and almost 80,000 likes on a single tweet, ignoring the countless other comments and posts resharing the picture.

The manipulated photos are created by AI text-to-image generators, which use written prompts to create a wide array of incredibly realistic images. Other popular subjects include former US President Donald Trump, billionaires Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, and American basketball player LeBron James.

In the midst of the online storm, the Pope addressed the issue of AI at a meeting late last month, where he endorsed the technology – with a caveat.

“I am convinced that the development of artificial intelligence and machine learning has the potential to contribute in a positive way to the future of humanity; we cannot dismiss it,” he stated. “At the same time, I am certain that this potential will be realised only if there is a constant and consistent commitment on the part of those developing these technologies to act ethically and responsibly.”

His warnings on the risks of AI may have garnered significant scrutiny, but they are not new.

Back in 2019, Pope Francis had already tackled the issue, claiming that new technology posed a tangible threat of an “unfortunate regression to a form of barbarism dictated by the law of the strongest”.

Moreover, the Pope’s recent words come in the midst of yet another tech-related controversy.

ChatGPT – a widely used chatbot launched by US-based lab OpenAI last November, renowned for its detailed answers and ability to produce university-level essays – has been banned in Italy since the start of this month.

The comical take? As one tweet suggested, the chatbot’s endorsement of putting pineapple on pizza – a culinary heresy in Italy – led to its immediate demise in il Bel Paese.

The reality is far less amusing: the Italian data-protection watchdog, Garante, blocked the tool over a set of privacy concerns, which it intended to investigate “with immediate effect”.

Now that other countries seem inclined to follow Italy’s lead, this latest move has further highlighted the increasingly heated debate on the potential threats and benefits of AI to society.

Pontiffs and technology: what’s the history?

Pope Francis is often portrayed as an innovator of sorts within the Catholic Church. While his predecessor, Benedict XVI, was often depicted as beacon of theological traditionalism, with a particular penchant for Latin and sacerdotal pageantry (the differences between the two Pontiffs itself immortalised in the highly fictionalised 2019 Netflix film, The Two Popes), Francis, on the contrary, has been heralded a harbinger of a modern, no-frills approach, blowing the dust off of the Vatican’s hallowed halls.

Given his relatable reputation, it may come as little surprise to the general public that the Pope would give his (hesitant) blessing to AI.

Nevertheless, Francis sits on a long tradition of Pontiffs cautiously interacting with and embracing the newest technological tools of their time.

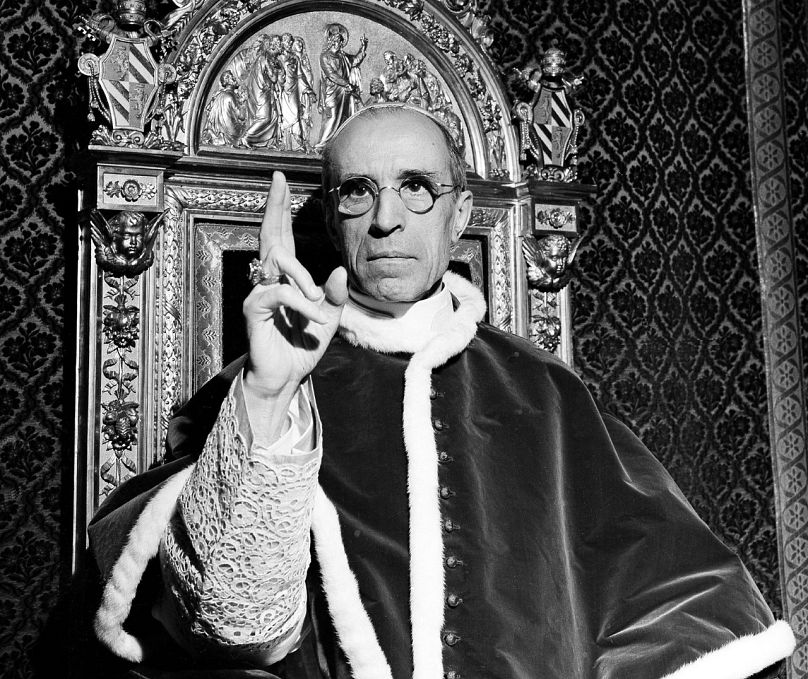

Almost seventy years ago, wartime pope Pius XII found himself having to embrace TV, then a fledgling new format that quickly revolutionised Italy’s social landscape after its debut in 1954. The medium was controversial at the time, especially among leftists and certain conservatives, who deemed it a cheap American product bereft of intellectual integrity, and feared it would corrupt the Italian public.

Pope Pius XII shared some of these concerns, and yet endorsed the medium – to the point where he was proclaimed the “pope of television”.

“We expect from TV consequences of the greatest importance for an increasingly dazzling exposition of the Truth,” he declared in 1957.

Fast forward 44 years, and Pope John Paul II made history by publishing an official document on the Internet, then a rapidly growing medium that had yet to reach the ubiquitous presence it now enjoys in our everyday lives.

The Pope’s support for the digital network was underscored with fears that it could deepen existing inequalities, yet he lauded it as a “new forum for proclaiming the Gospel”.

Following in his predecessor’s footsteps, Benedict – despite his reputation as an arch-traditionalist (John Paul’s own profoundly conservative theology notwithstanding) – became the first Pope to open a Twitter account, @pontifex, in December 2012.

"Dear friends, I am pleased to get in touch with you through Twitter,” it read. “Thank you for your generous response. I bless all of you from my heart."

The Catholic Church is often perceived as an unmovable bastion of tradition, yet its views and positions have changed over time – the 1962 Second Vatican Council being the most prominent in the past century – and its relationship with technology has been symbiotic.

“Historically speaking... the Church has been extremely technologically optimistic and progressive, perhaps more so than any other organization in the history of planet,” stated US-based professor and AI ethicist Brian Patrick Green. “However, this is not the current perception.”

Why has Pope Francis become AI’s unlikely star?

The recent flurry of AI-manipulated images of Pope Francis begs the question: Why has the Pontiff himself become a prime candidate for AI stardom?

For most commentators, the answer boils down to the several factors: Francis’s universally recognisable appearance, his elderly age, his stature as the head of the Catholic Church, and, above all, his purportedly “likeable” demeanour.

“I think Pope Francis has a certain amount of ‘cool’ to him, so that people want to work with his image and see what they can do with it,” Brian Patrick Green told Euronews Culture. “The images are amusing but they are also a warning - we need to be careful of what we believe, even if we see a picture of it.”

And this leads to the crux of the issue: Is the latest Pope-AI phenomenon the sign of something more ominous?

For some tech enthusiasts, like Rome-based writer David Valente, the surreal nature of the viral images are a playful way of highlighting AI’s potential dangers, and could thus serve a heuristic purpose.

“The images of the Pope are the simplest way of alerting as many people as possible to the risk of being tricked by an image,” Valente told Euronews Culture. “They are a useful tool to demonstrate the new risks and opportunities (of AI).”

Others, however, are less optimistic.

Among the many fears which experts have about AI technology, one of the biggest is that it could be used as a tool to further disseminate fake news and muddy the public’s trust in online information - and Francis’s fake photos further highlight this threat.

“The images of the Pope are very well-made, so much so that the only difference you notice is that he’s standing too much - which he wouldn’t be in real life, given the current state of his health,” said Paolo Benanti, a Franciscan theologian and Papal adviser on technology ethics. “The assumptions we have of what is true can be betrayed by AI.”

“The greater the power, the greater the risk,” he added.

To add further fuel to the fire, the Pope’s own comments on AI have themselves become the source of yet another AI-generated hoax.

Earlier this month, a fake screenshot purporting to show a tweet from The Telegraph’s official Twitter account included a fabricated quote attributed to the Holy Father, in which he supposedly claimed AI was a “means of communicating to God”.

“I thought the image of the Pope in a big coat was real,” wrote one journalist in a recent op-ed for The Guardian, highlighting how easily one can be fooled by the fake pictures.

And while many of the AI images are merely humorous and unlikely to cause any material damage to the Pontiff’s reputation, a select few – depicting him in a variety of unbecoming and questionable scenarios – could have a more nefarious impact.

“Doubts on the authenticity of texts, images and videos will lead to the proliferation of disinformation, propaganda and conspiracy theories which will be able to ‘produce’ evidence,” warned Andrea Pisauro, a neuroscience researcher at the University of Birmingham, while speaking to Euronews Culture.

“All of this doesn’t even take into account that actual AI interfaces are programmed to respond (honestly) to user requests,” he added. “But in the future, who can stop people from programming the tech to deceive people who use them?”