Elizabeth Siddal is much better known as the Pre-Raphaelites’ ethereal, enigmatic muse and Rossetti’s wife.

London’s Tate Britain opened a new exhibition last week entitled The Rossettis. It includes works by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, one of the Pre-Raphaelite group of English artists and poets still usually dubbed a “brotherhood.”

But the show turns the spotlight on an overlooked female member of the artistic circle, Elizabeth Siddal. According to the curators, The Rossettis is the most comprehensive exhibition of her work for 30 years.

The Pre-Raphaelites’ elusive muse

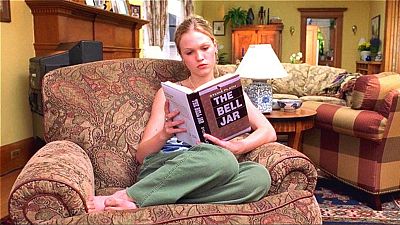

Siddal is much better known as the Pre-Raphaelites’ ethereal, enigmatic muse and Rossetti’s wife. With tumbling auburn hair and a pale, delicate face, she perfectly embodied the group’s aesthetic ideals.

The Pre-Raphaelites’ aspiration was to reject the trickery and technical virtuosity of the Renaissance period by seeking inspiration in the “truth” and “honesty” of medieval art.

They adopted stylistic traits and subject matter from Quattrocento Italian art. Their work deliberately contradicted the Royal Academy conventions for artistic training while exuding a mystic sensuality that was repressed in wider Victorian society.

Siddal the artist

Mythologised in biographies and documentaries as the Pre-Raphaelites’ melancholic muse, Siddal's artistic determination and influence over Rossetti have been long overlooked.

Griselda Pollock, in Vision and Difference, describes Rossetti’s art as the “usurpation of activity, production, creativity and health of Siddal” - she was merely the foil to Rossetti’s masculine creativity.

Siddal's languid fragility, a result of suffering from consumption, came to exemplify Rossetti's concept of beauty - and he was completely infatuated with her.

He drew countless sketches of Siddal and used her as literary and historical figures in his paintings, some of which are exhibited in the Tate show.

In his artworks, she is often sitting or lying passively, sometimes with her eyes closed, such as in Beata Beatrix, 1864-70. She is introspective and withdrawn, characteristics likely induced by her self-medication with laudanum but admired and augmented by Rossetti.

Her illness - which led to her premature death at 32 - is romanticised to an idea of unattainable and ephemeral beauty.

Poet Edgar Allan Poe once described the “death of a beautiful woman [as] unquestionably the most poetic topic in the world.” In Rossetti’s images of Siddal, beauty and death coalesce.

Siddal’s overlooked influence over Rossetti

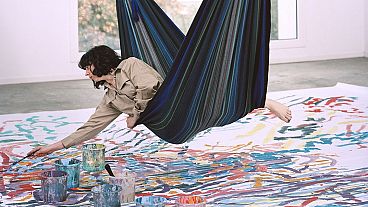

However, as the Tate exhibition demonstrates, Siddal produced a significant body of work that not only shows a distinctive style, but also how Rossetti drew inspiration from it.

Siddal did not receive artistic training but as a teenager she worked in clothes stores in London and taught herself dress design.

After being introduced to the Pre-Raphaelites, she turned her hand to drawing and painting as well as writing poetry.

The Rossettis showcases 17 of Siddal’s watercolours and drawings, including several previously unseen works, alongside extracts from Jan Marsh’s forthcoming biography, Elizabeth Siddal: Her Story.

Siddal’s artworks bring to life complex, imaginative worlds rendered in rich colour. They evoke medieval fantasies of love and temptation and loyalty and betrayal through intricate poses and gestures.

There are also poems by Christina Rossetti, sister of Dante Gabriel, interwoven around the artworks hung on jewel-hued walls.

The exhibition places works by Siddal and Rossetti side-by-side to demonstrate her influence on his work.

The pairings make it apparent how Rossetti adopted some of her ideas and style and marked his turning point from Pre-Raphaelitism to the more expressive Aesthetic style.

Thanks to this new narrative, the Tate exhibition has begun the significant process of disentangling Siddal from Rossetti's aesthetic fantasy, and being part of the push to bring recognition to overlooked female artists.