"I heard some loneliness in his voice." Nelson Mandela's ghostwriter Richard Stengel discusses the lost tapes of their time writing 'Long Walk to Freedom'

There’s probably one universal desire held by every journalist. That you get to interview and spend time with interesting people. For Richard Stengel, that desire couldn’t have been more fulfilled.

In the early nineties, Stengel helped Nelson Mandela ghostwrite his autobiography ‘Long Walk to Freedom’. Published in 1994, just a few years after Mandela was released from a 27-year term in prison, the book followed his journey from the son of a Xhosa chieftain, through his incarceration and to leadership of the African National Congress (ANC).

Stengel recorded over 70 hours worth of conversations with Mandela. But it was only recently that he revisited the tapes. Nearly three decades later, he reflects on the time he spent with one of the most influential of men in a new podcast, ‘Mandela: The Lost Tapes’.

“I met him about a year and a half after he came out of prison. He wasn't yet president of South Africa. I don't even think he was president of the ANC yet,” Stengel told Euronews Culture.

Throughout the process of writing the book, Mandela would go on to lead the party to its first ever victory in South Africa in the post-apartheid 1994 general election, making him the first president of the country.

“While we were doing the book, he was negotiating the constitution, negotiating a path to democratic elections and more," Stengel recalls. "The book was about the 150th most important thing he had to do every day.”

Despite the huge responsibilities, what is most striking about the tapes and Stengel’s experience, was Mandela's generosity.

Inside Nelson Mandela

Throughout the tapes, you hear Mandela’s deep competency. “He wasn't a micromanager. He respected people who were good at what they did and if he saw that they were good at what they did, he would just give them a free hand.”

But more than just his ability for work in a team, Stengel remembers Mandela’s sense of humour.

For a man revered for his serious role in South African history and global democracy, a sense of humour isn’t the first thing to come to mind. But listening to the tapes, they are filled with laughter and Mandela’s brilliant impersonations.

Listening back, Stengel came across a moment he’d completely forgotten about. When discussing Mandela’s meticulous prison exercise routine.

“I said something like, you did 50 fingertip press-ups a day. And he went like, ‘No man, I did 100 fingertip press-ups a day. And then he proceeds to unhook his microphone and get down on the floor. And he shows me that he can still do two fingertip press-ups which are not easy under any circumstance.”

At other points, we can hear the human behind the history as the pair bicker about Stengel’s refusal to have sugar in his tea.

“All those little insights into his personality and character, which was just incredibly gracious and warm. As wonderful as it was to hear that again, it also made me miss it again,” Stengel reflects.

Getting under the surface

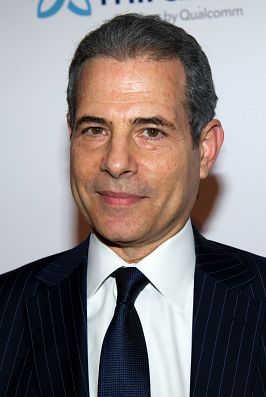

Stengel himself is an excellent storyteller throughout the tapes. It makes sense. Outside of working with Mandela, he’s spent time at the top level of journalism, as Time’s managing editor between 2006 and 2013, he’s published several non-fiction books, and even served as President Obama’s Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs in his second term.

Yet despite Stengel’s talent for interviewing, some topics with Mandela were harder to pry than expected.

One of the most obvious questions Stengel wanted the answer to was how Mandela had changed from the young man imprisoned on charges of overthrowing the state in 1962, to the older man released in 1990.

“He hated that question and resisted it and, until finally, one day, he said, ‘I came out mature’,” Stengel recalls.

“And that word, which may not seem like an enormous one to most people, was a gigantic one. To him, it meant self-control, self-discipline, all of these things that he learned in prison, that that young man who went into prison, as he described him, was a much more tempestuous emotional person than the older man who emerged 27 years later.”

It’s one of many revelations that come out of the tapes. Another effect of revisiting these recorded conversations is Stengel can now see Mandela in a different light. When they worked together, Mandela was in his 70s and Stengel was a young man. Now, he’s in his late 60s and empathises in new ways.

“I heard some loneliness in his voice, this time. Some sadness that I didn't hear before. At the time, I was just trying to get the information and to get colour through no anecdotes and emotion, which was very hard to get out of him.”

“I've also realised that his own upbringing in a royal household in the Transkeian Territories was just more basic to who he was as a person and how he saw the world than I realised before,” Stengel adds.

Now more than ever, he sees Mandela as a product of Victorian-era upbringing and the weight of being a descendent of Thembu royalty.

By Stengel’s admission, Mandela’s role in his life was far greater than vice versa. Releasing the tapes is Stengel's way of adding more to the historical record of the man. But it’s also to add colour and depth to the great humanity of the leader.

It wasn’t the last time they ever met, but Stengel remembers the final time they officially met for the book. After the mic was turned off they hugged.

“He wasn’t usually physical in that way. I embraced him and I felt very emotional and I thought about all the men and all the people over the years who had embraced him for strength who were facing terrible circumstances, maybe even death, who held on to him for strength. And I felt that strength from him. And I felt that he understood that that was his role, you know, sometimes a lonely role that he was giving strength to other people when he needed it himself. That was a powerful moment.”