For millennia swords have held deep cultural significance in both Asia and Europe. In this episode of Crossing Cultures, we head to Toledo in Spain and Longquan in China to meet the swordsmiths still forging in the ancient tradition.

Forged 2,600 years ago, the Longquan Sword was the first of its kind to be made from iron in Chinese history. At around the same time, Toledo in Spain was becoming a centre for swordmaking, with first Carthaginian general Hannibal and then the Romans becoming aware of the quality of the city's steel.

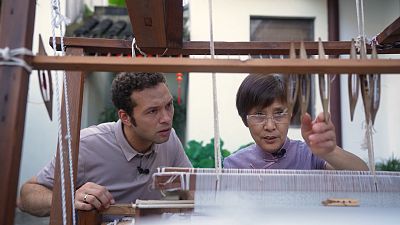

Longquan's master swordsmiths

The Longquan sword is one of China’s most iconic weapons and is listed as a national intangible cultural heritage item.

The iron sand found in Longquan gives the blades made here extra resilience and strength. Taking the unique minerals found in local rivers, bladesmiths in Longquan continue to follow the ancient forging process. This is achieved through a complex hammering process where the iron is repeatedly reheated to remove impurities to eventually forge the steel.

In days gone by only the very best craftsmen in China were permitted to become swordsmiths. Once forged, a special knife is used to shape and grind the sides of the blade. Getting the right balance is a real challenge and the swordsmith uses all his skill to alter the thickness and angle of the blade. Once this is done it is then reheated and quenched one last time before being polished and decorated.

Hu Xiaojun is one of Longquan’s most renowned swordsmiths. Passionate about tradition, his famous ‘Swords of heaven’ are forged from meteoric iron.

Showing a large piece of meteoric iron, he explains: “This is called the Widmanstatten pattern. It’s crystallised iron and nickel after hundreds of millions of years of cooling. It’s very complex."

The metal that made Toledo

Famed since Roman times, the quality of Toledo steel made it a hotbed for sword making. Bladesmiths in the city spent centuries refining the forging process - a secret that would make the swords from this part of Spain feared and revered worldwide.

Julio Ramírez is the city’s only master forger still making swords by hand. One of the last links to a tradition stretching back more than two millennia.

“Toledo steel is a technique that consists of welding two layers of steel on the outside, on the cutting edges and an iron layer on the inside. It gives us a very hard and very flexible blade in this way. This is the difference between Toledo steel, which is very resistant to shocks, and steel which is not Toledo steel, which would break. This is the difference,” says Julio.

To get both flexibility and resistance Julio tempers the blade, first by heating it to around 800 degrees Celcius. He then cools it in water. This gives the steel its strength. He then puts it back into the forge at a much lower temperature.

“We have to heat it up again, to about 250 degrees more or less. With this, we will be able to remove the inner tensions of the steel and in this way we obtain a more flexible blade," he says.

Once forged, Julio and the rest of the team at Espadas Mariano Zamorano shape, polish and mount the blades. Tourists are the firm’s main customers.

Throughout history, swords have held deep cultural significance, both in Asia and Europe.

But despite looking like similar weapons, often the fabrication and how the swords were used, weren't always the same.

“They look like the same weapon, but they are different weapons," says Santiago Encinas, Director, of the Toledo-based family business Espadas Mariano Zamorano. "The European sword is designed to be used with the point and to strike, not to cut, that's why it has no edge."

More than just a weapon

There is an old saying in China that a fine dance has to have a fine prop. That’s why dancers in China are often seen with something in their hands. This enhances the message they want to convey.

"In China a sword is both a weapon, and more than a weapon," says Hu Yang, Principal Dancer, at the China National Opera and Dance Drama Theater. "The sword doesn’t exist alone. It’s ingrained in our culture," he says.

Swords are popular as they magnify different emotions and also signify the status of the character.

Hu Yang adds: "Confucius used to transition the sword from a weapon as a symbol of power to a language of protocol. When it came to (Chinese poet) Li Bai, he used the sword as a brush to write his poetry. An artistic creation should combine with cultural content to show its intellectual side.”

Bringing the past back with a vengeance

While swords still hold symbolic significance in China, in Spain they continue to have a practical use. Within the splendour of Almodovar Del Rio’s magnificent castle, re-enactors from across the country regularly bring history back to life.

From the fighting to the armour and weapons, the medieval combat group Bohurt Zona Sur pays meticulous attention to detail to recreate the past.

“Our armour is based on the medieval ages, usually between the 14th and 16th centuries. And it’s completely authentic. It doesn’t matter what background and training you have, obviously it will help, you’ll always gain the skill as you progress,” explains one of the group's combat fighters, Samantha Chapman.

Fighting like this is not a recent phenomenon. Even in times gone by nobles and knights would train for fun.

“This sport is incredible, it pushes you to the limit, and this makes it amazing," says Medieval Combat Fighter Rafael Maldonado. "It feels like you're doing something historic, with thirty kilos of armour, everything, everything about it is epic and it's incredible.”