Why was the French New Wave important? We look at some of Jean-Luc Godard's stylings to see why people considered him a legend of filmmaking.

Our first part in a series looking back on the French New Wave and Jean-Luc Godard’s influence on cinema.

Once in a while there is a paradigmatic shift in the way people understand an art form. In film, the French New Wave was one of those times.

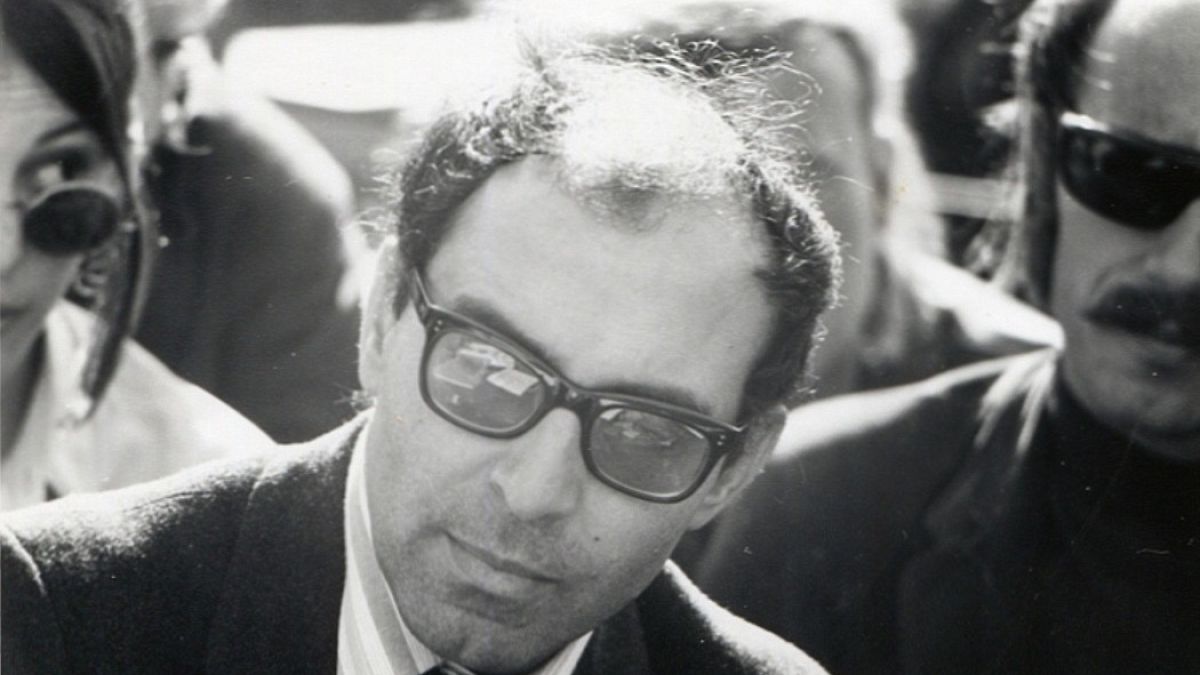

And at the heart of the artistic movement was Jean-Luc Godard.

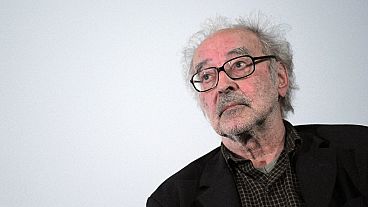

Godard, who died aged 91 by assisted suicide this week, was one of the last surviving members of the era.

Alongside François Truffaut, Alain Resnais, Éric Rohmer, Agnès Varda and many others, Godard paved a new approach to the medium. His death signals the passing of an epoch.

But what exactly defined the French New Wave? And how was Godard indelible from it?

The French New Wave style

Coming at a time when films were written about older people produced in big studios, the French New Wave was a breath of fresh air.

Godard ripped apart the rule book for film. What they should be about, how they should be filmed, and the ways they were edited were all up for grabs.

A Bout de Souffle (Breathless) from 1960 was Godard’s first feature film and is emblematic of many of the French New Wave stylings.

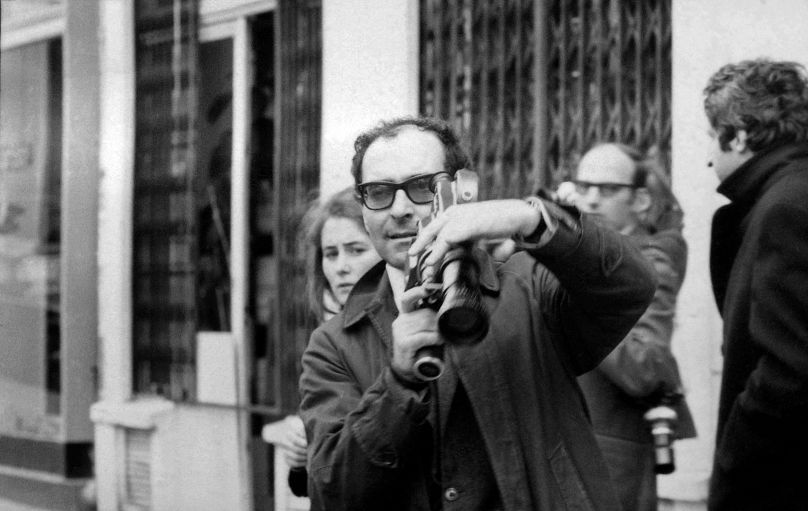

It was filmed on a low budget using handheld cameras that allowed Godard to move freely about instead of having the camera fixed in place.

The use of handheld cameras “came to typify the New Wave because it created a shaky, grainy aesthetic. A famous example is the scene on the Champs Elysées in Breathless,” explains Dr Darren Waldron, Senior Lecturer in Film Studies in Drama at the University of Manchester.

Godard could go out and film in the streets of Paris. Depicting the city and the lives of the young people at the heart of his film sounds banal today, but it was radical then.

Breathless’ protagonist Michel, played by Jean-Paul Belmondo, speaks directly to the camera and is obsessed with the actor Humphrey Bogart. The overt references to filmmaking itself was a defining quality of the New Wave movement.

Waldron points to the opening of Breathless where Michel discusses his interests and thoughts with the audience.

“Another example I like is from Godard’s Pierrot le Fou,” he points out, where another character played by Belmondo is asked who he’s talking to and simply answers: “the audience”.

Films that know they’re films

Godard was willing to have his actors play with the narratives that they were creating on screen conspicuously.

Dr Neil Archer, Senior Lecturer in Film at Keele University notes how this is in part because Breathless is a clear self-aware homage to 40s and 50s American films.

“That sense of putting a story in another context to make it look like a performance. Belmondo’s character is playing a role, he’s a character in his own film as a gangster who’s done this deed and the romance of the role kills him in the end. He can’t act, so he can’t live,” Archer says.

Part of the comfort in making film references and breaking the fourth wall is that the French New Wave was defined by a cohort of filmmakers who were film critics in their own right, Waldron points out.

Many of the big names started their careers writing for the magazine Cahiers du Cinéma. “It’s a natural evolution of their role as film historians to explore and make films as film criticism,” Archer says.

While Godard’s handheld techniques in the streets of Paris may at first strike a first-time watcher as the technique of an amateur, filmmaking was always a means of interrogating film for him.

Anarchic editing

The interrogation of film was reflected strongly in the way Godard approached the cinematic language of his storytelling.

“In Godard’s cinema in particular, the editing was often innovative, almost anarchic,” Waldron says. “He broke the normal codes of continuity editing, including inserting lots of jump cuts, which would give the film a jagged, jumpy aesthetic.”

“He also allowed characters to enter and leave the frame without having the camera follow them and seemingly randomly,” he continues, citing Le Mépris’ spontaneous acts and Godard's refrain from using artificial lighting as emblematic of his experimental sensibility.

“Such films / scenes disrupt the usual ways in which stories are told and could be said to distance the spectator or disrupt their conventional viewing practice because their attention is directed towards figuring out what’s happening rather than following the story. So, they may well be thinking about the form of the film rather than its content,” Waldron adds.

Films typically happened in chronological order before the New Wave, with scenes following a strict rubric: establishing shot of the location, then a breakdown into individual units and a clear through-line to the action.

Godard thought nothing of missing shots that weren’t absolutely essential to the point he was making. Sometimes, this would be a budgetary necessity, but often it was a pioneering montage style that influences editing choices today.

From non-linear storytelling devices to winks at the camera, Godard and the French New Wave created a visual language for film that communicated with its own art form and was willing to treat audiences as intelligent enough to keep up.

Stay tuned for our second part on Jean-Luc Godard’s influence on cinema.