After the Islamic Revolution, western music was banned in Iran. So how did people carry on listening to their favourite songs?

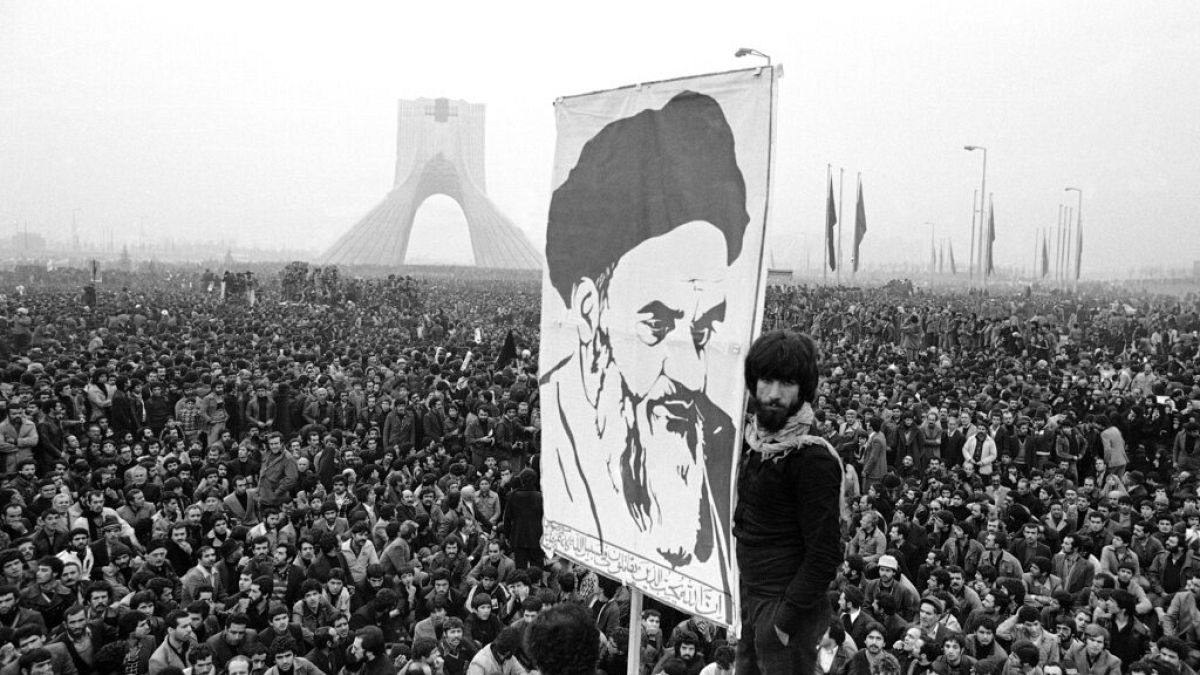

After the 1979 Islamic Revolution, music was criminalised in Iran.

Western songs were forbidden, record shops vanished and concert halls fell silent.

Anyone caught with music deemed 'un-Islamic' could be fined, lashed or imprisoned for 'causing corruption on earth' under Iranian law.

But this did not stop people from listening - far from it.

Before the revolution, Iran was ruled by a pro-western, modernising Shah (King), Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who allowed some degree of cultural freedom.

Most Iranians, having spent their whole lives enjoying western music, simply carried on listening to their favourite bands, while those born after the revolution were curious about other cultures.

‘Everything went underground’

Much like the illegal drugs market in Europe, cassettes and LPs were smuggled into Iran from overseas and distributed among people in secret.

Neighbouring countries, such as Turkey and Iraq, were the most popular sources of musical contraband, but a lucky few got music from friends and relatives in the West.

“It was hard to access original, high-quality tapes,” said Darya Hosseini, who was a teenager during the 1980s. “We usually only had access to a copy of a copy.

“Of course, the quality was not the best,” she laughed. “But during those days, we were somehow careless about quality. All we wanted was the newest releases.”

As the Islamic government tightened its grip on society in the years following the revolution, western music was hard to come by and expensive, with prices soon doubling, trebling and quadrupling.

But, over time, it became easier to find as a large black market developed. By 1986, the latest hits in the West would reach the streets of Iran within just a week.

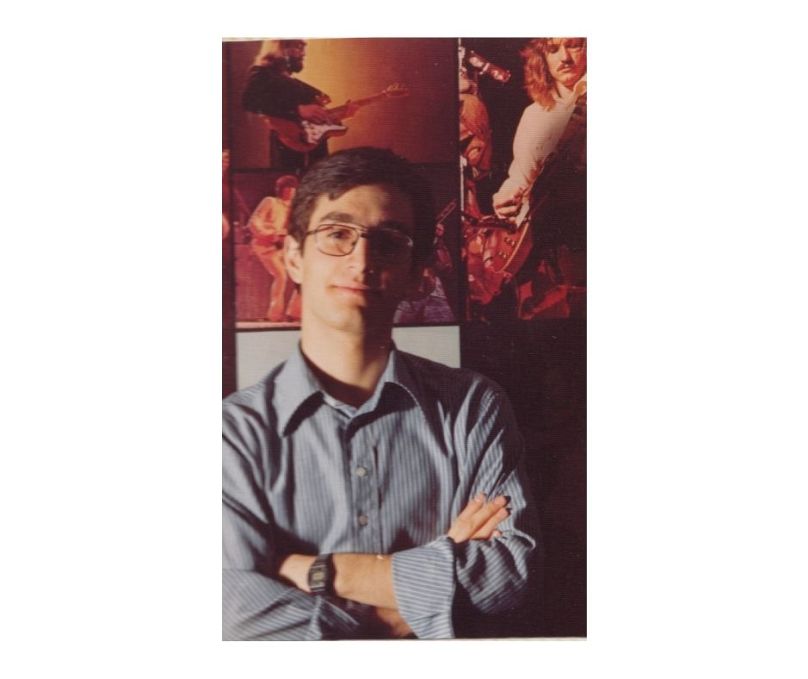

“You could get everything in the black market,” said Maziar Bahari, an Iranian-Canadian journalist and filmmaker. “Even the most obscure types of music.”

His favourite artists at the time were Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd and David Bowie, with a teenage Bahari religiously listening to Zeppelin’s ‘Immigrant Song’ every morning for months.

“I would put my head in-between two big speakers and blast them as loud as I could,” he said. Much to his mother's dismay, who would rush to his room and tell him to turn it down, fearing the neighbours would call the police.

“Pink Floyd's popularity in Iran was on a different level,” says Bahari, "if they were to come here even now, there would be 10 million people at the concert.

“Some had the prophet Mohammad and the Shia Imams as their saints, while a lot of us had David Gilmour, Roger Waters, Robert Plant and Jimmy Page as our idols," he added.

‘It was a dangerous business to sell pop music’

The wide availability of music was largely down to the efforts of dedicated dealers who earnt their living hawking bootlegs down the back alleys and side streets of Iran.

“In some areas of the city, when we were passing by, a random guy would whisper tapes, tapes, tapes,” said Hosseini.

According to her, these sellers acted like gatekeepers, showing people up-and-coming bands and new releases. “Most of the time, we would get updates from dealers themselves. As we walked in the streets, they would whisper things like ‘Metallica's new album is here.”

With punishments so harsh, a constant worry was if sellers could be trusted, as there was always the danger of entrapment or betrayal.

“We were scared and there were huge risks,” said Hosseini. “But this was part of the process. Doing something considered illegal became fun and exciting after a time.

“We felt like rebels,” she added.

One ex-seller, who wished to remain anonymous, told Euronews he started selling tapes after a relative brought him back a Metallica tape from the US.

He made copies of it at home and sold them to his friends, even translating the lyrics into Farsi word by word with a dictionary.

“Nothing I translated made sense, but I made 200 dollars that summer,” he recalled. “I am getting nostalgic.”

‘Devil worshippers music’

But things were not all plain sailing for sellers.

After the revolution, vehicles were routinely searched at police checkpoints. If tapes were found, they would be passed through a large magnetic device to wipe their contents.

“Sometimes they would even give you back the empty tape, and I’d try to record over it again,” laughed the former seller.

Still, this was getting off lightly. Zealous ‘morality police’ hunted down distributors, tossing those caught in jail or slapping them with heavy fines.

Aged 17, Bahari was arrested and put in a 30-man cell packed with “murderers, drug smugglers and rapists”, after being caught in a cafe with his girlfriend and a couple of cassettes by The Doors and Queen.

“The police really took it seriously,” says Bahari. “I was chastised and insulted. They called it devil worshipper's music and said it would make me immoral.”

Yet, despite their best efforts, the authorities could not stop the tide of tapes and LPs being snuck into Iran not only by sellers, but ordinary people.

During the Iran-Iraq War, Hosseini’s brother, an army conscript, was posted near the Iraqi border. Here it was easy to find smuggled western tapes, alongside band’s T-shirts and other merchandise.

Her brother, also a “big music fan”, would bring musical souvenirs for the family.

When she got a particularly sought-after album, Hosseini said she would show it off to her friends at school, sneaking it past the security inside her bra.

‘Music filled the void in our lives'

The 1980s were one of the hardest periods in Iran’s history.

Some 500,000 Iranians were killed in the country’s bloody war with Iraq, while the new government implemented a hardline Islamic regime and ruthlessly suppressed all those who resisted it.

“Music was really helpful for us mentally,” said Hosseini. “It gave us courage when we played it at our secret parties and gatherings.

“That music to me, the people around me and I guess the majority of people in my country has no expiry date,” she continued. “It has become part of Iranian history after the revolution.

More than escapism from hardships, music had a political point.

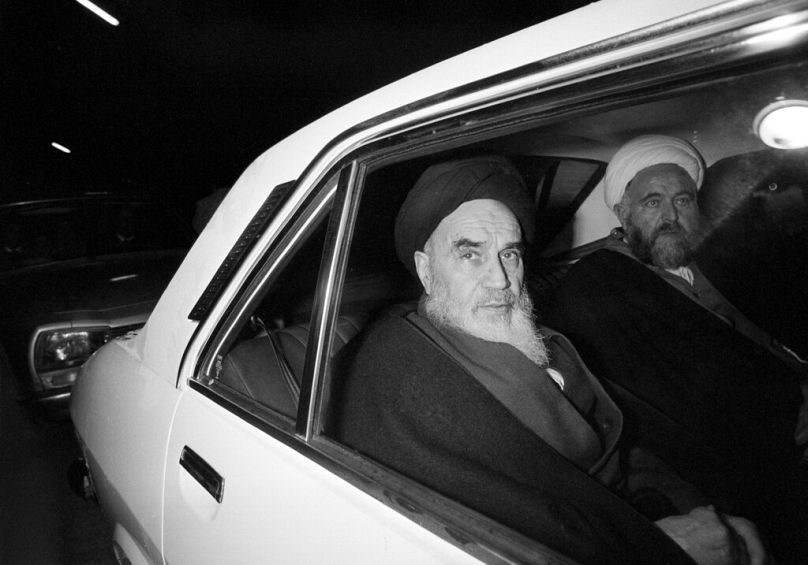

“Cassettes were like a weapon in Iran,” said Bahari. “They were used by Khomeini [former Supreme Leader of Iran] before the revolution to distribute speeches and give people messages while he was outside the country.

“After the revolution, listening to music and dancing together … became an act of resistance because we did not want to conform to what the Islamic government was telling us to do.

“It was a form of protest,” he added.

What came out of this situation has stayed with Bahari for life.

“Listening to music is not something I take for granted because I always remember how we had to fight and struggle to listen to it,” he said.

This left Bahari with a “deeper appreciation” of how powerful culture was in challenging authoritarian regimes.

“I began to see that music, films and paintings really crack the veneer of dictatorship by affecting people’s hearts and minds. Whereas giving people news or political activism can have an important effect in the short term, the impact of culture is much more long-term and deeper.

“You have to cherish it,” he added