The Supreme Court of the US will decide whether an artwork by Andy Warhol is significantly different from the photo it is based on. The verdict will change how artists work in the US.

The Supreme Court of the United States has agreed to take on a case to decide whether a piece of Andy Warhol’s work is its own creation, or just a copy of someone else’s work. If Warhol’s work is found guilty, it could change artistic free-use rights in the US forever.

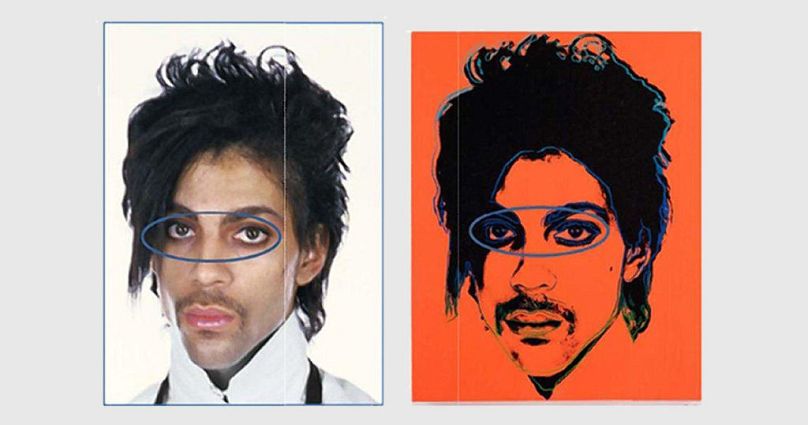

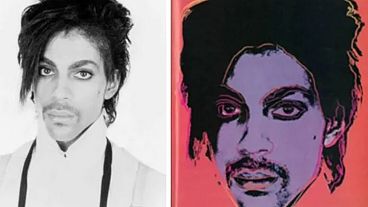

The artwork in question is Andy Warhol’s Orange Prince piece. Warhol used a portrait photo - taken by Lynn Goldsmith - of US musician Prince, and then created a series of silkscreens to alter the photo to put Prince’s image in high contrast black and white with an orange background and luminescent highlights.

Orange Prince has been compared to other portraits by Warhol, including his Marilyn Monroe paintings. His 1964 'Shot Sage Blue Marilyn' will go on auction this year and is expected to sell for $200 million (€180m), which would make it the most expensive 20th century painting.

But while Warhol’s Marilyn works have hit the headlines for all the best reasons, when Orange Prince was garnering attention it was the beginning of a copyright feud.

The original photographer

Lynn Goldsmith, the original photographer, first became aware of the paintings in 2016. A prolific photographer of rockstars, Goldsmith took her portraits of Prince early in his career in 1981. After Prince released his mega-hit album Purple Rain in 1984, Vanity Fair licensed the photo from Goldsmith for $400 so that Andy Warhol could create his artwork.

When one of the artworks Warhol created for Vanity Fair was reused by Condé Nast after Prince’s death in 2016, it is claimed that Goldsmith threatened to sue the Andy Warhol foundation. However, Goldsmith denies this.

Regardless, the Andy Warhol Foundation hit back with their own lawsuit that wanted a court to declare the artworks as non-infringement. Counter-suing back, Goldsmith sought a permanent injunction which would stop the foundation from further reproducing or selling works from the Prince series.

The case went back and forth in lower courts until it was accepted by the highest court in the US, the Supreme Court.

Goldsmith’s argument is that the Prince series is not a “transformative” work of art that substantially changes what she originally did to create her artwork.

In an amicus brief filed to the Supreme Court by Goldsmith, she explains the dedicated work she put into creating the portraits including the visible makeup she applied “where light glints off the singer’s glossed lower lip”.

The brief also notes how details including “the reflections from Goldsmith’s photographer’s umbrellas in Prince’s eyes remain visible in Warhol’s series”.

A lower court, the Second Court of Appeals, found in Goldsmith’s favour that the Warhol work was not a “transformative” work, which is allowed by US copyright fair-use laws based on Goldsmith’s arguments.

This is what prompted the Andy Warhol Foundation to take the case to the Supreme Court. They claim that if the decision stands, there could be “a sea-change in the law of copyright” and that the decision “casts a cloud of legal uncertainty over an entire genre of visual art, including canonical works by Andy Warhol and countless other artists.”

The free-use doctrine of copyright law is what allows artists to create adaptations of other artists’ work that become wholly the new artist’s work if they are sufficiently transformative - “whether it adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message.”

A history of artistic copycatting

Artists, Barbara Kruger and art academic, Robert Storr, weighed in on the issue, writing their own amicus brief to the Supreme Court. They argue that although copyright is important for artists to fairly get compensation for their efforts, it would be dangerous to take these restrictions too far as art may suffer.

“Copying was a key component of renaissance art in Europe,” they write, noting the schools of Leonardo and Michelangelo which birthed many great artists in their own right. Beyond the renaissance, copying works to create new ones has also been seen. Manet’s “Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe” uses key elements from “The Judgement of Paris” by Marcantonio Raimondi and an earlier version by Raphael.

More recent examples include Marcel Duchamp who took a postcard of the Mona Lisa and doodled a moustache on her. Rebelling against concepts of originality, Duchamp’s “appropriation of one of the most famous paintings of the Western canon, and his deliberate injection of silliness into a painting treated with the utmost deference, is a deliberate effort to undermine the self-seriousness he saw in much traditional European painting.”

Even Duchamp’s work has been copied to create new art, with Sherrie Levine casting the urinal used in Duchamp’s iconic “Fountain” work to make a bronze piece called “Fountain (After Marcel Duchamp)”.

Kruger and Storr fear that if Goldsmith is successful at the Supreme Court, the definition of fair use could change. Instead of requiring a previous definition of transformation, it would now require that the new art has not been “recognisably derived from” the former.

“Requiring that an artist make some undefined but significant visual changes to an original work for the new work to be “transformative” is an arbitrary, judicially-imposed limitation on artistic freedom, which disregards long-established practices of artmaking and unduly limits the kinds of commentary and repurposing that artists may legally engage in.”

“The effect of that approach will be to discourage artists—especially up-and-coming artists who may lack the resources needed to fight protracted legal battles—from creating some of the works that most powerfully represent and assess contemporary society,” they write.